[This article first appeared in the September 1988 issue of Chronicles.]

“Le reve est une seconde vie.“

—Nerval

T.S. Eliot has become so thoroughly exalted, especially among conservative intellectuals, as the greatest poetic avatar of Western civilization in modern times (a role he must share, though, with Yeats and Pound) that it may shock many to notice the unmistakable oriental elements embedded in even his most overtly Christian works. It happens these same elements also inform his early and patently anti-Christian verse as well. Accordingly, I intend no slight to the great traditions of the Christian West (neither did Eliot) by trying, in brief compass, to give some indication of where and what those elements are.

First, there is probably no better way to go desperately astray in the study of Eliot’s verse than to try to read his almost absurdly conventional body of criticism into it. Unfortunately, this is precisely what some, of this poet’s admirers have done, producing an effect of dogmatic certitude almost entirely at odds with the extremely disturbing texture of Eliot’s poetic. Eliot, perhaps even more than the overtly atheistic modernists, is a poet of inconceivable disruptions of traditional continuities, a quiet forewarner of understated Apocalypse, an affirmer of Christendom in the face of its obvious collapse from within. Yet in this faithless age, Eliot became a poet of faith. And exposure to extra-occidental influence had something to do with this.

When Thoreau broke the ice with Whitman in Manhattan (“You seem to have come under the influence of the oriental philosophers”—a New Englandly transcendental remark if ever there was one). Whitman’s thoroughly un-Harvard-Yardly reply was “Oh? Tell me about them!” By contrast, but in the same spirit of guileless grace, the sophisticated Mr. Eliot, who had studied a little Sanskrit at “The Place” with Irving Babbitt, parried a late challenge that his Christianity seemed a great deal more like Buddhism with, “Perhaps I’ve not been found out yet?”—a nonchalance in keeping with his general disavowal of the importance of poetry itself (“Poetry is a mug’s game”).

He may have meant life is a mug’s game. A universal illusion-disillusion is central to all Eliot’s verse. He faces not only modernity’s forced reappraisal of the West’s now-staggering heritage (that man is a perfectible creature of reason, say, making “progress” in a coherent moral creation presided over by a caring and available Creator) but also faces an interior crisis of consciousness, as well:

These with a thousand small deliberations

Protract the profit of their chilled delirium,

Excite the membrane, when the sense has cooled,

With pungent sauces, multiply variety

In a wilderness of mirrors.

Which in Sanskrit would have been called a recognition of máyá (illusion)—that reality itself is finally nothing but a convincing dream we are willing ourselves to believe in, a “wilderness of mirrors,” in which we are so absorbed that we cannot awake.

Paradoxically, dreams are also considered to form the language of an immortal, higher existence (here Buddhism and Platonism are virtually agreed), and it is in this sense that the word “dream” appears in Eliot’s verse with astonishing frequency:

Eyes I dare not meet in dreams

In death’s dream kingdom

These do not appear.

Swinging between life and death

Here, in death’s dream kingdom

The waking echo of confusing strife

Is it a dream or something else

When the surface of the blackened river

Is a face that sweats with tears?

Wavering between the profit and the loss

In this brief transit where the dreams cross

The dream-crossed twilight between birth and dying . . .

These are not daydreams, drug hallucinations, or (as the Freudians would have it) “thinly disguised death-wishes.” Not only is the use of the term “dream” very technical here, indicating prophecy and visionary experience analogous to Cavalcanti’s and Dante’s, but the place itself (the same in each passage) is real. The phrase “death’s dream kingdom,” which clearly appealed to Eliot, indicates a specific psychic state between life and death, exactly like the pagan Underworld of Homer, Vergil, and Dante—though Eliot undoubtedly “knew” those poets microscopically, it is the lived experience that impresses in these passages—and for this stunningly vivid place Buddhism has a term: it’s called bardo, or gap.

As it happens, there is exactly no possibility that Eliot cribbed a knowledge of the bardo from Sanskrit, since the doctrine was developed in Tibetan and translated (almost unreadably and incomprehensively) for the first time after Eliot’s passages were composed. It would have required a greater miracle to derive these haunted and concentrated images from Evans-Wentz than to have made them up, though Eliot’s not inventing here. He’s doing what true poets do: writing down what he sees. This is one place you can’t describe without having been there. Notice in all these passages the persistence of disembodied eyes:

In this last of meeting places

We grope together

And avoid speech

Gathered on this beach of the tumid river

Sightless, unless

The eyes reappear

As the perpetual star

Multifoliate rose

Of death’s twilight kingdom

The hope only

Of empty men

The apparition of these eyes as cause of hope, hope of deliverance from this dismally barren plane that is not (as in the Christian view) after death but between life and death, cannot be explained by any orthodox manipulation of Christology. Only in the canzoni of Guido Cavalcanti, the avowed heretic, do we come even close. The rose, we may feel, has been merely borrowed from Dante’s Paradiso, whose Christian Good News has been willfully (demonically) inverted. Yet that is not adequate to explain the psychic desperation evoked here, which turns on the notion “empty” in an absolute contrivance of dirge about “lost kingdoms” (hardly the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires) titled “The Hollow Men.”

There are some tangible sources, of course, and they are even mentioned in the “notes” to The Waste Land. The effigies “Leaning together / Headpiece filled with straw” are discussed in the “Adonis, Attis, Osiris” sections of Frazer’s Golden Bough. They are fashioned to represent these various grain-cult gods (who are the same god) in the other-worldly interval between death and rebirth. So they are not descriptions of modern men at all, though Eliot undoubtedly intends us to take them so. They are certainly puppets, and though it is specifically implied that “we” are not “lost / Violent souls” (i.e., we’re not even alive enough to be damned), it is the notion of the soul at all that matters.

In the conception of nous made explicit in Plato and adopted by the great medieval Fathers as a perfect predescription of Christ’s teaching, there are three minds—mundane mind, soul, and spirit—operating on three distinct planes of being: the material, the dream, and the light of divine mind itself We deal here with soul, whose modality is dream. In the East what we have always called soul has been traditionally known as the body of dream, capable of separation from the physical body and of direct knowledge even before death, on that plane called bardo.

It is to this bardo-plane that Eliot’s imagery has brought us, not for reasons of intellectual exhibitionism but because he has simply been there himself The dream-body and the faculty of dreaming have both structure and purpose (about which Freud, the Romantics, and today’s druggies have all equally been wrong), by having made contact with dream, people with no physical approximation at all in disparate ages of man have been able to come to remarkably like conclusions about the otherwise hidden aspects of being in the cosmos. So, in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the vision of disembodied eyes—Eliot’s hope—does occur. The eyes appear precisely in the context of that mysterious quality of “empty” that the poet cites—not in despair (as we persist in misreading) but in hope.

What we want to believe Eliot said, that the vision of eyes in the rose is empty men’s only hope, is not at all what he has said. What he has said is that this vision may be the hope only of empty men, that men are hopeful only when emptied—emptied of all illusion, emptied of the notion of self, emptied of the consuming desire that has—as in the Buddha’s Fire Sermon that forms the core of The Waste Land—set all the objects of this world on fire. This is exactly what takes place in the unfinished Sweeney Agonistes, with its grim insistence that life consists only of “birth, copulation, and death,” and its explicit epigraph from the mystical poet St. John of the Cross:

Hence the soul cannot be possessed of divine union until it has divested itself of the love of created things.

The Buddha had a term for this, what Eliot calls

A condition of complete simplicity

(Costing not less than everything) . . .

The term is sunyata. It means emptiness.

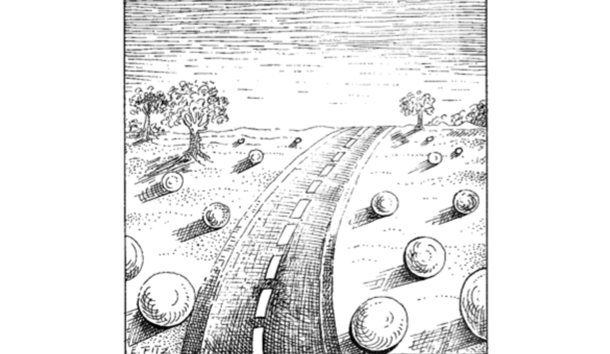

This emptiness is not the same as existential nothingness (it is its exact opposite) though the fashionable nothing-world does figure heavily in Eliot’s work as an object of satire:

In the land of lobelias and tennis flannels

The rabbit shall burrow and the thorn revisit.

The nettle shall flourish on the gravel court.

And the wind shall say: “Here were decent godless people:

Their only monument the asphalt road

And a thousand lost golf balls.”

The Buddhists’ emptiness is a form of cosmic modesty. Nor is there really any doubt that Eliot actually possessed it. (“Poetry is a mug’s game.”) By contrast, Allen Ginsberg and Robert Duncan (who both have tried to siphon off for their own aggrandizement the New Age faddishness of Tantrism-mania) are certainly mugs—reveling in the Kali Yuga (the Age of Putrefaction) whose prophets they presume to be. But they are not poets.

Opening the heritage of the West to the East, Eliot was able to renew the faith purchased for us with the blood of Christ, and so

Here the impossible union

Of spheres of existence is actual . . .

and it is the divine body that can make such a union for us if we still desire it.

Perhaps, as Eliot intimated so slyly after all his poems had been written, printed, and endlessly explained by those whose self-importance depends upon such things, he hasn’t been found out yet? Perhaps it’s time he were?

Leave a Reply