I’m not sure how it happened, but recently I found myself watching a Canadian musician on YouTube named Peter Pringle as he conducted a lament for Gilgamesh, the titular hero of the ancient epic. Wearing a yellow mock turtleneck, Pringle delivered the performance using a replica of the Gold Lyre of Ur that he commissioned. The original is considered one of the world’s oldest stringed instruments. He sang the entire thing in Sumerian, based on text that was rediscovered and translated by Westerners. His video has more than 600,000 views. Not bad for an antediluvian tune.

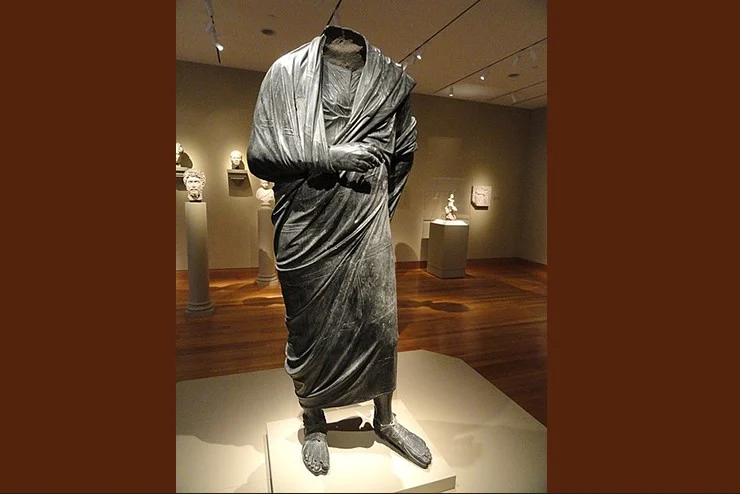

I thought about Pringle when news broke that the Cleveland Museum of Art had decided to surrender a bronze statue of Marcus Aurelius to Turkey. The move is the conclusion of a joint effort between the office of Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. They claim that the headless likeness of the Roman emperor was illegally smuggled out of the country in the 1960s.

Cleveland put up a fight, contesting the seizure in court, but lost in the end. It’s a shame, because the statue would be better off in the United States. Turkey’s efforts at protecting cultural artifacts are generally considered to be underwhelming. Understaffed and underfunded, to say nothing of the threat of violence and terrorism in the region, their record is not good. The West is simply a better place for the protection of these artifacts.

When Turkey went around demanding the return of antiquities in 2012, curators from Los Angeles to Paris and Berlin pointed out that its campaign ran contrary to the UNESCO convention that allowed museums to keep foreign artifacts acquired before 1970. Philanthropy News Digest noted that Turkey’s tactics included “delaying the licensing of archaeological excavations and publicly shaming museums.”

It was naïve to think Turkey would abide by such lofty goals as international cooperation for the preservation of human art and culture. Turkey’s effort has always had little to do with the protection of priceless pieces of history and much to do with resentment for the West. The row over the Cleveland collection is more evidence of that animosity, as illustrated in a comment by Mehmet Nuri Ersoy, Turkey’s minister of culture and tourism: “With international collaborations, we are retrieving our stolen artifacts one by one,” he said.

In other words, it’s not about ensuring the continuity of culture for the sake of posterity but the taking back of “our stolen artifacts” from grubby Western hands. The same hands that, ironically, developed and professionalized the very science of archaeology, which has made it possible for present and future generations to touch the otherwise inaccessible roots of the past.

The West is unique in the sense that it has sought to understand and preserve not only its own history but that of disparate civilizations. Now, it is true that the Chinese practiced a rudimentary form of antiquarianism, the precursor of archeology, to gaze back into the mists of their past. But it was Europeans in the West who took the study of one’s ancestors and conceptually broadened that into an interest in “ancient history” as such—as a means of cataloging the entire material record of human existence on this planet.

It was Westerners who deciphered the Phoenician alphabet, the earliest known to man, unlocked the mysteries of the Rosetta Stone, uncovered the Ziggurat of Ur after it had been lost to time beneath the sands, dug out the enigmatic Sphinx of Giza, and rediscovered the Mayan city of Chichén Itzá. To think strictly in terms of “our stolen artifacts,” as the Turkish regime does, is to reveal only a profound insecurity and smallness of vision.

When discussing the Peloponnesian War, Athenian partisans will sometimes say that the only reason we know as much as we do about Sparta is because Athenians (and other non-Spartans) wrote about them. I think you could make a very similar case about much of world history and the West.

Leave a Reply