I told myself not to go Oprah, but I just couldn’t help myself.

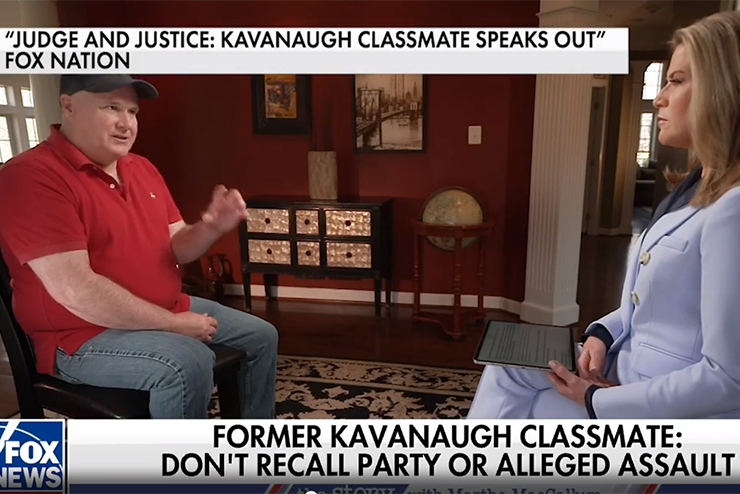

In February, I was interviewed by a Fox Nation documentary team because of my involvement in the 2018 Brett Kavanaugh hearings. The subject is in the news again because Christine Blasey Ford has a new book out detailing her crusade against the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

I became briefly famous when Ford accused Kavanaugh of sexual assault at a high school party she said occurred in 1982. Ford claimed that I had been in the room when the assault occurred. Brett and I were friends in high school. Ford’s story was refuted by everyone she claimed had been there.

The left and its media accomplices tried several methods to get me to play ball with them. I have written in some detail about their methods—including a potential honey trap, witness tampering, and attempts at extortion—all to get me to help them sink Brett. All these tactics failed.

And yet the psychological fallout for me has been intense.

So here I was, talking to a Fox News journalist about suicide. It was only a small part of the interview. They had filmed me skateboarding, in a bar, and in front of Georgetown Prep, the Jesuit school where Brett and I had become friends in the 1980s. I said that a lifelong love for skateboarding had taught me “how to fall and get back up.” One of the young members of the Fox News crew is a rider himself, and it put me at ease when he noticed I’m a “goofy foot”—meaning I ride with my right foot forward. He began adjusting every shot to account for that. To me, skateboarding had always been an original American art form—one that embodies freedom, daring, and honesty. It was a great metaphor for explaining what had happened to me during that time, and it was the thing that helped to save me when my life seemed to be falling apart.

Yet, as I talked about it, there was this stuff about suicidal ideation creeping back again.

I started experiencing these thoughts after the 2018 attack from those I now call the American Stasi: the axis of media, government, and activist fanatics who take it upon themselves to destroy the lives of those who dare to stand in the way of their power. As emotions ran high, I found my Irish pride swell and I tried to prevent the words from coming out of my mouth—especially while being filmed—but it was too late. I was going to be on Fox Nation talking about ending my own life.

Suicide has been a common outcome for those who have been traumatized by totalitarian regimes. In my book The Devil’s Triangle: Mark Judge vs the New American Stasi, I argue that the Stasi, the East German secret police under communism, serves as a much better analog to the modern American left than the over- and often mis-used term “Nazi.” Many Germans who suffered under both have claimed that the Stasi were even worse than the Nazis. There were more of them, for one thing, and they spied on everyone. Many of the victims, as depicted in the great film The Lives of Others, were so thoroughly humiliated and devastated that they lost the will to live and committed suicide.

Still, it would not come to that with me. Not only am I a skateboarder, I come from a long line of tough Irish Catholics, having grown up in the same D.C. “Catholic ghetto” that produced Pat Buchanan. We punch back.

In the Fox interview, I felt a great catharsis in finally being able to publicly discuss the actions of the people who had tried to destroy me: people such as Emma Brown at the Washington Post, the reporter who broke the Blasey Ford story on Sept. 16, 2018. Brown first contacted me via email on July 11, 2018—one day after she met with Ford in California. In her email, Brown mentioned nothing about Blasey Ford. Neither did she mention an alleged assault. Instead, her tone was very upbeat and fun: She said she was just doing a story about Brett and Georgetown Prep. As we now know, there was nothing friendly or honest about Brown’s inquiries. For example, when Brown published her story on Sept. 21, she left out crucial and important details about Ford’s story, such as the part about Leland Keyser, a woman Ford said was at the party in 1982. That was probably because Keyser denied that such a party ever occurred. Keyser said she didn’t even know Brett Kavanaugh.

The media was adept during this time at ignoring information inconvenient to their narrative. Take the matter of Bernie Ward. He had taught sex ed at Georgetown Prep back in the day. In 2018, he told the media that “the drinking was unbelievable” at Prep and that we all had a lot of sex with girls. There was only one problem: Mr. Ward had been arrested for trafficking in child pornography and spent years in prison. Few outlets reported that inconvenient fact.

There was also media darling Michael Avenatti, the “celebrity” lawyer—now memory-holed—who accused Brett and me of running a drug and gang rape cartel in the 1980s. When a woman claiming she had been victimized by us said she had filed a police report, I was overjoyed. No rape took place, I knew, so there could be no police report. Yet the only reporter willing to pay the fee to try and discover this alleged report was the tiresome Los Angeles Times liberal Jackie Calmes. When the woman kept changing her story, Calmes gave up, burying that information in the back of her error-filled book.

Then there was Ruth Marcus at the Washington Post, who believed she could explain why Blasey Ford never contacted me over the summer of 2018 with this line: “She thought about contacting Mark Judge but didn’t know how.” I’m a journalist who is all over social media. Ford didn’t know how to contact me? And Marcus believed this?

Watching the Fox crew prepare their documentary was interesting. It brought back memories of my father, who had been a writer for National Geographic. All my life it had been artists and creative types who encouraged and supported me. Too many conservatives, unfortunately, don’t really know how to do art, and we don’t take care of our own the way the left does. Had I buckled under the pressure and lied about my friend Brett, there’s a good chance I would have been rewarded with jobs and speaking engagements—and my book, like the one Christine Blasey Ford just published—would have gotten a big advance from a mainstream publisher and prominent placement in the biggest bookstores. But I couldn’t sell my soul to do that.

The Fox crew also interviewed my editor, the great Adam Bellow at Bombardier Books, and asked him about why there was so much pop culture in The Devil’s Triangle—particularly the pop culture of the 1980s when I was a teenager.

The answers are simple. First, part of the 2018 assault on Brett (and all of us from Georgetown Prep) was an attempted lynching not only of us but of the freewheeling 1980s. I wanted to defend the Reagan era and the milieu in which we lived. Writing about the culture of the time was necessary because it was, in effect, another character in the story. It would describe the people that the media were ready to send to the stake and the books, movies, and bands we all loved. For many of us coming of age in the 1980s these things—from Star Wars and the novels of Anne Tyler to the songs of Donna Summer and the art of Andy Warhol—made us feel excited and happy about being Americans. And that fact, especially, made the left hate us.

I did not want The Devil’s Triangle to be a typical conservative book—full of policy, bouts of righteous anger, and lacking heart. Andrew Breitbart famously said that politics is downstream from culture; I didn’t see any reason why a conservative memoir that talked about the insanity of the left shouldn’t also celebrate novels, movies, photography, skateboarding, and even punk rock. Indeed, it was the people I knew from these sectors of my life who came to my rescue in the aftermath of the Stasi assault.

Joseph Bottum, a veteran conservative author, put it this way in a tweet: “What they did to Mark Judge was despicable, as was the failure of those who had published him to defend him. So he winds up washing dishes.” Yes, I did wind up washing dishes. The only bad review The Devil’s Triangle received came from The American Conservative. (I never responded because the piece is incoherent.) National Review has ignored me completely.

Many of the people who have supported me since the Stasi attack are not even conservatives. Rather, they are the eccentrics from the social and artistic corners of my life. There’s my libertarian buddy from high school who doesn’t care for either Brett Kavanaugh or Joe Biden. There’s the model and beauty contest winner I had professionally photographed and befriended and the bar owner I’ve known since I was a teenager.

I have befriended a talented young conservative filmmaker who, like me, has abandoned any hope that the right will recognize and support his talent. My filmmaker friend, on the other hand, was not surprised when a well-known and successful Hollywood actor called me in 2018 to express his disbelief that no conservative had bought the film rights to my story. The actor told me that all the elements were there: “It’s a psychological thriller and courtroom drama with a 1980s soundtrack,” he said. “You could do it for $15 million and it would reach millions.” Instead, we get Lady Ballers, the Daily Wire comedy about that underreported subject, transgenderism. When it comes to the arts, conservatism is not a meritocracy. We don’t find or support genuine talent. We hire our relatives or friends.

One of the interesting things in The Devil’s Triangle is how my photography and filmmaking somehow found an enthusiastic supporter in the actor, Alec Baldwin. I know, I know, I’m supposed to say that Baldwin is an unhinged leftist who can’t even fire a gun properly. Still, I would trust him over any number of conservatives in the business to adapt The Devil’s Triangle to the big screen. Baldwin, perhaps more than anyone, knows that imperfect protagonists make interesting characters. And it is that understanding as an artist, not rigid application of ideology, that makes for good art.

To be fair, however, the Fox Nation crew covering my story in February also seemed to understand the nuances involved in presenting imperfection and authenticity as they filmed. They seemed empathetic when I talked about suicide. Above all, I think it was clear that they appreciated how I didn’t try to hide from my shadow. As human beings, we are inundated by stories in a media landscape, always striving to reduce everything to an infantile narrative of good guys vs. bad guys (always, of course, framed with left-leaning assumptions about the good). It is too easy for the right to give in to the temptation of pushing back in ways that accept this narrative. The truth is always more complicated than the narrative, but our attempt to understand the truth is what defines our humanity.

Leave a Reply