First things first. In the briefly intersecting histories of rock and roll and Pentecostalism, it is recorded that Jerry Lee Lewis, at age 15, was expelled from Southwestern Bible Institute in Waxahachie, Texas, for unrepentantly playing a boogie version of “My God Is Real.” In view of the depth and breadth of the Jim Bakker-PTL scandal, it seems only reasonable to ask: Should Southwestern Bible Institute reconsider its decision?

PTL. The letters have become almost as much a part of the cultural alphabet as CBS and ABC (or IRS and FBI). Their familiarity grew along with the scandal, a scandal that provided irresistible media fodder, news from all directions, something for everybody. The story had sex, money, and power; and we were given the details, the numbers, and the standings.

The only thing we didn’t get is what the story had most of Religion. The reason we didn’t get religion is that the people asking the questions—journalists—didn’t speak the language of the people with the answers; and the people with the answers—like Jerry Falwell—knew enough not to do any helpful interpreting unless it served their purpose. The evangelical appraisal of sin against God was as relevant to this particular story as the legal question of fraud in God’s name. The media responded to this confusing situation by shoving everything under the all-purpose label of “Gospelgate.” Once they learned the difference between a Fundamentalist and a Pentecostal, journalists more or less called it quits. (They had a harder time with the distinction between a Pentecostal and a “charismatic” and usually just grabbed whichever term came to mind first.)

What was missing in the reporting on PTL was relative perspective. Context. The necessity to place a question and expect an answer within a given context—are we in the Fundamentalist’s mentality here, or “the world’s”?—was something journalists couldn’t, or wouldn’t, grasp. As often as not, their ignorance appeared deliberate, a kind of left-handed requirement of “journalistic objectivity” regarding religion. After all, the Fundamentalist’s mentality centers on “the evidence of things not seen.” And “news” by definition excludes the evidence of things not seen.

The fascinating upshot of all this objectivity-by-default was that Jerry Falwell, a man supposedly on the hotseat, got one of the longest free rides in media history. Moving in and out of context at will—a promise of “openness” here, a biblical defense there—Jerry Falwell finessed every reporter he talked to. And he talked, it seemed, to every reporter there is. But his skill—and his luck—didn’t stop there. He maneuvered even within context, using Scripture both to define Jim Bakker’s sin and disavow “judgment” on it, to threaten Jim Bakker and “forgive” him.

Within the religious story that didn’t get reported were the religious questions that didn’t get asked: Reverend Falwell, in the case of Jim Bakker, are born-again Christians to follow the biblical directive to “judge not, that ye be not judged,” or are they to “reprove” the “unfruitful works of darkness”? Both? How? And how does one “restore” the brother one is working overtime to keep at bay? Jerry Falwell has answers. And the people with the most at stake in the matter—Fundamentalists of all denominations—would have found his answers instructive, in one way or another (which is why, given his current role, Jerry Falwell probably was relieved not to be asked). Everybody else might have found the answers interesting.

Instead, we got Larry King, with his hey-I’m-just-a-regular-guy style, calling Jerry Falwell “Jer” and James Robison “Jim.” (Jer never flinched. But Jim—who is called James—looked half startled, half peeved and demanded to know, “Are you talking to me?”) When all else failed, Lar just slapped his forehead and said, “What’s goin’ on here?”

Well, what was going on here? Plenty was going on, and not just in Charlotte or Palm Springs or Lynchburg. As the PTL revelations mounted and the cast of characters grew, the editorial commentaries began appearing—the analyses, the overviews. Most of these reflected the corrosive attitude that on its face a betrayal of public trust is nothing; it counts as disheartening only if one is a member of the public in question and has personally proffered the trust. If not, let cynicism and glibness prevail: The weasels are everywhere, and the suckers abound. It was an attitude from which emerged expressions of class hatred and religious bigotry, along with extremely selective questions about the market system.

Writing in The New Republic, Henry Fairlie got himself so worked up that he finally claimed Fundamentalism contains “no theology” and therefore cannot be “religion.” His proof? Fundamentalism’s crude insistence on “personal faith” and a “personal reading” of the Bible, both of which ignore “established and authoritative interpretation.” This is an interesting, if predictable, approach to the pesky guarantee of “free exercise” of religion. If you don’t really have a religion, well . . . And what qualifies as a religion? Apparently, it’s whatever belief Henry Fairlie decides is theologically sufficient to pass his test of “established and authoritative interpretation.” (And just to keep things interesting, there is the fact that Fundamentalists themselves use the weapon of “established and authoritative interpretation” to challenge religious beliefs they oppose, like Mormonisni. At the moment, however, the Mormons, the Fundamentalists, and Henry Fairlie are all still in business—and who says America doesn’t work?)

Mr. Fairlie also offered what is by now the standard characterization of TV evangelism’s followers: “the vulnerable, the anxious, the largely ignorant, the lost, the afraid, and the all too often poor.” It is possible this characterization is accurate. It’s also possible that every person on earth, with the exception of Henry Fairlie, has suffered at least one of these conditions from time to time. In any case, how would Henry Fairlie know? This obviously is not the kind of crowd he hangs out with—he being “a European” reared on a Bible that “had been strengthened by centuries of interpretation by many of the best and most devout minds in Western civilization.” Gosh.

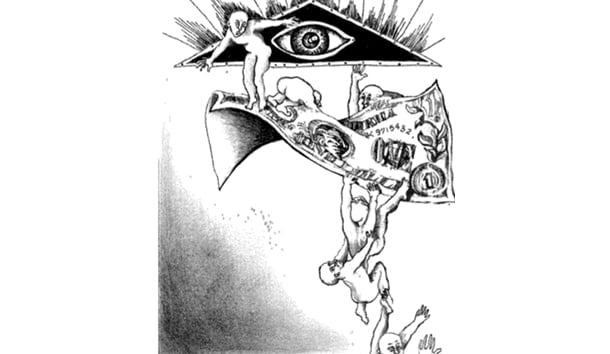

Mr. Fairlie’s parting instruction was that we are to count all TV evangelists “among the servants of Mammon.” Always, it comes down to money. Actually, it comes down to an objection to the very idea of money, carefully disguised as an objection to “greed.” Since the PTL chaos started, some critics of television evangelists have done everything but come right out and say it: How is it that those loony bumpkins get millions of dollars and smart people like us don’t? The answer has to be that they are “servants of Mammon” and that their followers are ignorant dupes of the servants of Mammon.

In fact, TV evangelism is a perfect working example of the economic principle of “perceived value” (not to be confused with the idea that there’s a sucker born every minute). The principle turns on a simple question: Do the people letting go of the money believe they’re getting their money’s worth? That is, do they believe they’re getting their money’s worth? (One is cautious with this principle. It can be misappropriated as a defense of relative moral values. Its actual function is merely to explain the success of such stuff as good rock and roll and bad rock and roll, pet rocks, and $120 Gucci pens. And TV preachers.

There is no law against a widow (to use the preferred example) giving her rent money to Jim Bakker’s ministry. There are, of course—need it be said?—legal and ethical limits on what Jim Bakker, as a minister, can do with the money. But there are no limits on the widow’s own interpretation of her action; there is no one with the wisdom or the prerogative to perceive on her behalf the value of her decision. And the fact is, even after all the investigative and regulatory agencies have had their welcome and proper say about Jim Bakker’s financial free-for-all, the perceived value of his ministry, past or future, is left to the determination of the ministry’s supporters.

That reality is beginning to sink in on the critics of religious television, and their pained awareness of it is leading them into dangerous territory. Stirring beneath the outrage is the implication, the hint, that the real issue isn’t the public accountability or fiduciary responsibility or use of the public airwaves or even tax exemption—ways to prevent evangelists from getting money; the real issue is simply to stop people from giving money—an elemental solution that not only puts an immediate end to religious frauds (i.e., all TV preachers) but also protects the poor and the ignorant from their own misguided perception of value. The poor and the ignorant, we are told time and again, have rights. Agreed. And for the time being at least, they have the right, just like the wealthy and the educated, to do with their legally acquired money whatever they legally choose. (Opponents of TV evangelism have so far been unable to rationalize the existence of what might be termed “the rich and the ignorant”; for instance, the wealthy dog-track owner who responded to Oral Roberts’ latest message from God with a million-dollar check. Is he being victimized? If so, is it because he’s ignorant? If not, why?—because he’s rich?)

The PTL saga might have ended there, a story that began with Jim Bakker’s excesses, moved on through Jerry Falwell’s PR dazzler, and wound up with yet another ideological manipulation of the idea of The Poor. But then Jim and Tammy Bakker went on Nightline. For an hour. To explain things. And we moved into another realm altogether.

Ted Koppel, described endlessly as “tough but fair,” began the interview by asking the Bakkers if they were going to “wrap [themselves] in the Bible” at every opportunity. The question was tough; the question was fair. It was also, considering who he was talking to and why, sort of . . . dumb. What did he think they were going to wrap themselves in—the IRS statutes? In any event, it was the last question of the interview that mattered, the last time in the whole PTL mess that relative perspective would be a factor. From that point on, Jim and Tammy Bakker were a context unto themselves.

Revelations about the Bakkers’ Christian stewardship had centered on personal spending so unrestrained it seemed less a case of corruption than addiction, and business practices so irresponsible they seemed less self-serving than suicidal. Now, here was Tammy Bakker, vibrating tension as always, defending her shopping “hobby” with a crazyperky “But I’m a bargain hunter!”

And here was Jim Bakker, ethically stunted, childlike in the worst sense. He sounded like nothing so much as the manipulatively charming youngster who’s got himself cornered, saying, in effect, I know I made a mistake, but somebody else made me do it, and anyway, I’ll never do it again, honest, and if you don’t believe me you can watch me, and I’ll even remind you to watch me, really. Together, the Bakkers were a contest of negative possibilities. Which was worse: that they actually believed what they were saying, or that they were intentionally blowing smoke? That they didn’t know any better, or that they did?

Before the hour was over, however, Jim Bakker righted himself, he found his direction, he rallied. He mentioned his hope for a new ministry, something called Hurting House. He talked of his “dream” of going back on television. And he asked—several times—that “the people” write to him, that they let him know what they think, “how they feel.” The ultimate test of perceived value.

And proof that what goes ’round comes ’round: Almost 40 years after an inveterate rock and roller was kicked out of Bible college for putting boogie licks to “My God Is Real,” an incurable TV preacher was doing a gospel version of “Got My Mojo Working.”

Leave a Reply