Having been invited to address the topic of manners, I can only do so with a certain embarrassment, for I have been known to have behaved deplorably. Indeed, I was once even called “reprehensible” by a woman of repellent aspect, remotely connected with education, but, all things considered, I felt more honored than not. I consoled myself with the unvoiced reflection, If I thought my thumbs could ever find the windpipe somewhere deeply buried m the wattles of your bloated neck, incredibly large person, I’d show you something “reprehensible.” But having been at fault on occasions all too numerous has taught me a few things, such as not to insult anyone unintentionally; not to lose my composure; and not to telegraph a punch. You know, experience counts for a lot. And so does theory.

Now, when the subject of manners comes up, I can only say that I know good manners when I see them, because I have indeed seen them, though not so much in the last 40 years. I do not claim any other authority on the topic, but perhaps I can begin by saying that I at least hope we are cured today of the romantic disgust that many have felt for Lord Chesterfield’s letters to his son. In our own time, J.P. Donleavy has written brilliantly on manners. In general, we need to get back to traditional standards in order to recover some reason, dignity, and peace, but things are not looking propitious. Specifically, I would like to see a revival of dueling, but that would be too much to hope for.

What we need today, and what we are not going to get, is a return to the 18th century, at least to understand the truth of Rochefoucauld’s maxim that hypocrisy is the tribute that vice pays to virtue. Such a tribute is no bad thing. An examination of the etymologies of person and hypocrisy is most instructive, striking at many of our modern vanities and illusions. Reading, as I did the other day, that Hollywood films have “revealed social hypocrisy” is to suffer a temporary vertigo. Society is hypocritical by definition, as humans always knew until Rousseau and Rameau’s nephew; and the arrogance, greed, and coarseness of Hollywood have hardly been a basis for any revelation. Even if they had been, the illusion of film and of contrived scenes only confirm—they do not deny—the ancient wisdom that all the world’s a stage.

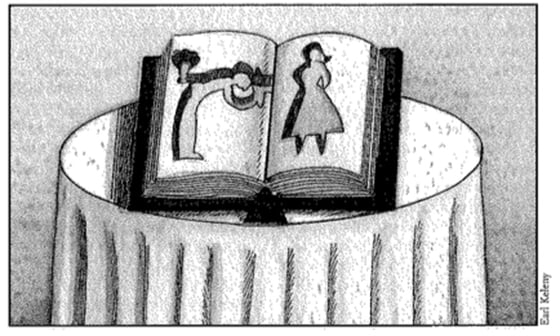

Shakespeare was certainly not the first to give voice to that insight, but he developed it as no other has done. I have always thought that Hamlet’s paradoxically rude injunction to his mother—”Assume a virtue, if you have it not”—was sage advice. Hamlet recommended hypocrisy, and this is in a play with a play within the play, to cite only one of many paradoxes. Hamlet’s manners are mostly bad—at Ophelia’s funeral, unforgivable—but noble in the end. Horatio is a gentleman. Claudius’s manners are deceptive (when they are not gross). Osric is a fop, a travesty of good manners. And Polonius is justly slain for his meddling and, above all, for talking too much.

I suppose that, when we think of manners, we think of literature, because that is where we see manners fixed—manners as character, as in 18th-century comedy, and as in such novels as those of Jane Austen. That toady, the Rev. Mr. Collins, and his esteemed patroness, the odious Lady Catherine De Bourgh, are unforgettable, as Austen brilliantly renegotiated the meanings of class and manners in her time. That heap of infamy, Uriah Heep, pretended clumsily and villainously to good manners above his station, as melodramatically imagined by Dickens. But by the time of Dickens, the rot had already set in. That great romantic hero, Heathcliff, was significantly ill bred, unkempt, and rude. Emily Brontë, more than Dickens, admired “sincerity” and “passion” all too well, with sinister long-range implications. Thackeray spent his career examining the meaning of good manners and gentlemanliness, with mixed results. The end of the road, I suppose, was D.H. Lawrence, and the sick charade of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier.

The American tradition of manners has always been rough—perhaps because of the frontier, and perhaps even more because of resentment of class distinctions. The results have not always been pretty. We are not taught to remember the Tories as gentlemen today, though perhaps we should. Fictionally, if not in fact, we have rooted for stout Brom Bones to drive out the bookish Ichabod Crane. Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, whatever their virtues, are an unlikely pair of heroes. In the national mythology, there was once an obsession with the idea of the gentleman, particularly the Virginia gentleman. We have documented reasons for believing that the Virginia gentleman existed, as in the language and behavior of Robert E. Lee, for example. The correspondence of the young A.P. Hill (from Culpepper, Virginia) with George B. McClellan regarding the proprieties of their conflict over the courtship of a young lady is highly suggestive, coming from two future generals in the Civil War. When Hill was in his grave, McClellan said of the man who had competed for his wife’s hand, and who had attacked his army ferociously during the Peninsular Campaign and at Antietam, that he was a gallant soldier and a gentleman. But the ideal of the Southern gentleman (not to mention such Northern ones as Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Winfield Scott Hancock) has long since been discredited in the minds of those who did not feel that theft, arson, and pillage in any way marred what their eyes had seen: the glory of the coming of the Lord. He works in mysterious ways. The fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword included stealing the wedding rings off corpses exhumed for the purpose, but enough of this unpleasantness. Let us just try to be grateful, shall we?

So there is a tradition of good manners to fall back on, from Europe and even from our own history. What do we know about good manners? Good manners are, by definition, harmonious with good sense and good taste, and should not need elaborate cultivation. Good manners are always effortless, as Castiglione would have it. Good manners are never mannered, because that is to call attention to oneself and one’s affectations, which themselves are usually signs of insecurity or new money. My father liked to point out that, when Winston Churchill declared war on Germany in a letter to Hitler, he signed off as “Your obedient servant.” To that point I would add, however, that Churchill, like Dr. Johnson, is also remembered for certain ungentlemanly moments, and he can hardly be faulted for those. He lived in the 20th century with the Labour Party, so what do you expect?

The truth is that we have a difficulty in our country today, and have had for a long time, with good manners: They have largely been discarded. James Fenimore Cooper had a lot to say about this in The American Democrat, and so did the Adams brothers later on. The implications of “democracy” were clear: Scruples are for losers. Was it not Jay Gould who once declared, after some speculative fiasco, “Nothing is lost, save honor”? The statement speaks volumes, and that was well over a century ago.

In the realm of popular culture, as an inheritance of Victorian melodrama and through Hollywood, we have long since been inured to regarding a man who speaks precisely and wears a suit as a villain. Various roles of Basil Rathbone, Clifton Webb, George Macready, Ray Milland, James Mason, and others prove the point, which is that good manners, if reinforced with the slightest claim to authority, are the sign of an evil disposition. The mean old banker will foreclose on the widow, but the nice (though unwashed and ill-clad) ranch hand will save the farm and little Lindy Lou. The point is a demographic one: There were not enough crooked lawyers to fill the seats, even a hundred or 50 years ago. Nowadays, of course, I would like to meet a crooked lawyer in a dark, pinstriped banker suit, because that would be such a refreshing change; but then again, I do not live anywhere near Washington, D.C.

Since the days of corny villains, there has intervened a new dispensation, which perhaps began when Marlon Brando undertook the role of Stanley Kowalski in 1947. Say what you like, but old Marlon was all too successful. The revelation of “truth” by way of violence and, what is worse, bad manners set a ruinous course for the last half of the 20th century. We have long been inured to misreading Tennessee Williams’ play, to accepting yelling as a revelation of deep feeling, and to believing that the lower strata of society constitute a source of moral instruction. In rapid order, after the actors mumbled in their T-shirts and Elvis Presley gyrated his hips, we had the civil-rights movement, which, its legitimate goals notwithstanding, sanctioned not only the disruption of public order but the principle that the disenfranchised, the aggrieved, and the young always know better about everything. We have had the feminist movement, which, aping its predecessor, established gross truculence as an argument and as a model of femininity, as the image of Molly Yard, roaring and shaking her fist like Mussolini, attests. And we have had the “gay-rights movement,” which celebrates its foundation in a 1969 riot at the Stonewall Inn, which has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places, as Bill Clinton made sure to point out.

The images of manners in popular culture today are only too well known, but perhaps I can cite a few of the more annoying codes. For males: Never stand up straight, sit up straight, or wear real clothes. Giggle and smirk a lot. Never tuck shirt in. Neglect haircut, shave, and education. Mumble leeringly and make constant jokes about contraception. For females: Display navel, with or without ring. Appear to invite immediate sexual assault by provocative slut-talk and stylish state of undress. Giggle leeringly about contraception and AIDS prevention. Cite equality of “genders” in all exchanges. Only meeting polite and composed people, which we sometimes unaccountably do, can prevent us from despairing as we behold the degraded images offered to us in the media and in “reality” as well.

Yes, thinking about bad manners is more fun than defining good manners, so perhaps we should cite some negative examples. I do not want to go out on a limb, but I do think there are some things that are simply “not done”—which means, in our world, that they are routine. I am not going to say that you should not talk with your mouth full or that you should keep your elbows off the table. May I suggest, however, that giving your word is something to abide by? The repudiation of agreements freely entered into, followed by bald-faced lying about it, is a phenomenon I now find less baffling than I did formerly, having experienced it so many times, but I hasten to say that such a thing does not happen in the academic world exclusively. I thought effrontery had topped itself when one liar I called to account suggested that I must be having mental problems. Well, he had me there: My mental problem was that I had a memory. I have actually known such things to happen in the real world, and from editors in Manhattan, three times. One of them invited me to come see him, and then abandoned the appointment, for which I had traveled many miles, on the grounds that he had a superior immediate opportunity. Another invited me to talk to him and then dismissed me as though I had not been asked to be there. A third (I do not remember him and there is no reason why I should, but he was some sort of British twit) insulted me while I shook his hand, at a reception to which I had been invited to meet him. Thus, I began to get the picture about the social code of Manhattan, which is superior to that of the rest of the country, as we have been so often informed.

Speaking of Manhattan, I must also say that some of the finest gentlemen I have known lived there. Lionel Trilling, Mark Van Doren, and William F. Buckley, Jr., come immediately to mind. Another gentleman, Bassett Hough, a professor at Barnard, disappointed me a little bit when I found out he was originally from Virginia, as I should have surmised. I was more than disappointed later on when, as he was on his way to play the organ at a church service, he was murdered for the lunch money he had in his pocket. Such an outrage seemed the destiny of an old gentleman in such a world.

But we cannot neglect the ladies, for they are one of the reasons for good manners, and they sustain them by their own example. My maternal grandmother, Mary Ligon Cason, was a lady who not only had excellent manners but much humor and a good heart to go with them. Her generosity to people of all stations is something I have never forgotten. The late Sally Fitzgerald was also a great lady of the old school, and I was glad to learn that she was from Texas, not from Massachusetts. (It figured.) Priscilla Buckley, whom I met a few times in New York, has always been known as a lady of impeccable manners, and her gracious presence is enough to make a day. Of course, I have named these three as exceptions.

The collapse of manners in the last two generations has been so widespread that it has actually masked a shift even more sinister than ugly clothes, ugly music, and ugly tones. The feminist motto that the personal is the political is not only wrong but wicked, and it speaks directly to the death of much that makes life worth living, which is, of course, why it was instituted. The breakdown of the distinction between the public and the private is an expression of the politicization of individual exchange, of the invasion of ideology into hitherto privileged spheres and spaces. The worst infractions of good manners I have known have been inquisitions at private gatherings —investigations of political correctness disguised as “conversation.” Political examinations have largely taken over the place formerly reserved for social exchanges, as I have seen many times. There was the late professor of psychology who announced to me abruptly, “I’m glad Clinton was elected. There will be more abortions, and that’s good.” I once attended a large dinner party for various academics at which the unannounced agenda, one I had somehow failed to intuit, was literally, “What can we do to reelect Bill Clinton and protect reproductive rights?” The delightful five-hour discussion that followed was so exasperating that I had great provocation but little need to suggest that various professors and their wives depart for the infernal regions immediately, and not wait for the dessert course, because we were already there. I realized that sometimes it feels good to be a bad boy. Come to think of it, today it almost always does. There comes a point when good manners have to be dispensed with, and to me that point can be identified when Satanism, tricked out with silverware and napkins and shrimp on the barbie and every amenity except the one that matters, is presented as good manners.

Only in the context of a code of manners, however distantly remembered, is it possible meaningfully to say, on occasions that are not hard to imagine, “Does your mother know who your father was yet?” or “Why don’t we continue this discussion outside?” or, more positively, “Why, there’s nothing I’d like better than to chaperone the gay prom—I thought you’d never ask!” And finally, let us remember that a great social philosopher once indicated that the hangman is the foundation of the state. Our ultimate Emily Post or Miss Manners is the cop on the block or in the cruiser. The temptation to take justice into your own hands and to seek the immediate satisfaction of personal honor is best addressed by the reflection that the cops pack heat. And, after all, who do you think would be sitting on any hypothetical jury, if you survived to be arrested? In a world of inverted values in which rage and resentment are institutionalized, and in which the ideological chip on the shoulder is permanently installed as everyone pursues a spurious “equality,” we can hardly expect anything better than what we have. In a mass democracy such as ours, except for admirable individuals and nostalgic rituals, there can be no manners but bad ones.

Leave a Reply