Thrice-rendered Enderby slenderly lives again. In the 1974 novel, The Clockwork Testament, Anthony Burgess dispatched to eternity his gross, grotty, gastric poet; New York City slaughtered the luckless English bard with a heart attack. But here he is again in Enderby’s Dark Lady. “I think we have to look at it this way,” Burgess says. “All fictional events are hypotheses, and the condition of Enderby’s going to New York would be that he should die there. If the hypothesis is unfulfilled, he does not have to die.”

In other words, the wildly self-absorbed Dickensian character who first appeared some 20 years ago has shrunk to the level of a pretext. Burgess has discovered additional targets for satire. Why not dig up Enderby, set him to writing the libretto “for a ridiculous musical about Shakespeare in a fictitious theater in Indianapolis”? Not a bad idea, at first glance. Enderby has lost nothing of his talent for dyspeptic observation and bilious remark. Here are his impressions of a Midwestern patroness of the arts:

He! knew that Mr. Schoenbaum was dead from making money. Mrs. Schoenbaum was clearly enjoying her widowhood. She wore a kind of harem dress of silk trousers and brocaded sort of cutdown caftan. Her silver hair was frozen into a photographed stormtossed effect, clicked into sempiternal tempestuousness on a Wuthering Heights of the American imagination. Her eyelids were gold-dusted and her lips white-lacquered. Her nose looked as though its natural butt had been surgically cut off. She took Enderby by the hand and led him into a salon….

I’m sure,’ she said, ‘you know nobody here.

Enderby’s Dark Lady contains numerous passages of equal malice and brilliance, and in these passages lies all the justification for the novel. Enderby himself becomes paler, more ghostly, with each new incarnation. Burgess seems to have lost interest in him as a character and now uses him merely as an observer. He has not even bothered to tell a new story. It is repeatedly–repetitiously–Enderby’s fate to meet a belligerently contemporary avatar of the Muse, and then to be impotent with her and to show himself puling and ludicrous in her eyes. Surely the point of this story is strong on first telling; Burgess has now told it three times, and it has lost force and plausibility.

The structure of Enderby’s adventure has become arbitrary. Enderby’s Dark Lady begins with a short story set in Elizabethan times; the last chapter is science fiction. According to this odd epilogue, no one wroteShakespeare’s plays; the poet himself cribbed them from time travelers carrying copies of his work.

Sandwiched between these strange episodes is the picture of Enderby in Indiana, wrestling with insipidly goofy song lyrics, down-home black culture, provincial theater, weak American tea, hard American slang, and the puzzling April Elgar, latest incarnation of the Muse with whom Enderby is doomed to fail.

In this encounter Burgress fails also. His sureness in female characterization deserts him when he comes to draw the celebrated black singer. It is clear that Burgess admires the real-life model April Elgar is drawn from (probably more than one model, “Elgar” suggesting enigma variations), and that he believes that Enderby can become infatuated with her. But he does not convince us that there was ever a chance of success, and so there is no suspense. The anticlimactic conclusion is known from the instant that April and Enderby meet. If April is the slovenly poet’s “cruelest” encounter, “stirring dull roots with spring rain,” she is also the most unreachable. A gray hopelessness vitiates that whole aspect of the story.

What we are left with is Burgess’ wit, which is rich, dark, bookish, sometimes strained, and almost always telling. Enderby having become what he is, there is little point now in wit at his expense, but Burgess will be able to produce entertaining books almost at will simply by shuttling this flatulent figure about the globe and allowing him to say what he sees. Not the grandest of ambitions, but Burgess is conserving his ambition for other books.

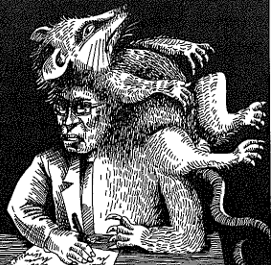

If Burgess treats his literary types with something less than full Christian sympathy, William Golding, in The Paper Men, is positively savage. This is ![]() a curious quality to remark, since Golding’s narrative line, for about half the length of the novel, is gentler and more humorous than Burgess’s. For quite a while, infact, The Paper Men is reminiscent of such Henry James stories as “The Lesson of the Master” and “The Figure in the Carpet.”

a curious quality to remark, since Golding’s narrative line, for about half the length of the novel, is gentler and more humorous than Burgess’s. For quite a while, infact, The Paper Men is reminiscent of such Henry James stories as “The Lesson of the Master” and “The Figure in the Carpet.”

Wilfred Barclay is an English literary lion stalked by an American academic, Rick Tucker, who proposes to write the Official Biography of Barclay and needs only Barclay’s signature on a contract. Tucker is armed with grants from American institutions and with the financial support of a mysterious philanthropist named Halliday. And Tucker is determined. Look here, he has even offered up his wife Mary Lou as bait.

But he has mistaken the nature of his prey. Overwhelming literary success has destroyed Barclay. He is still lecherous at 60 years of age, but recognizes his broken capacities. His marriage has failed, and one reason for its failure was a hilariously improper revelation made by Tucker. Barclay is alcoholic and has begun to slide into hallucinatory stales. Although he eludes Tucker and flees literally round the world, he seems to see the scholar everywhere, a pursuer inescapable.

Now a story like The Paper Men, one which begins plausibly enough and then shades into hysteric exaggeration, offers ripe opportunity for humor, and there is plenty of harsh satire in the book. But Golding has chosen to force his reader’ credulities, to take his characters seriously both as persons and as allegoric figures, topush his plot into madness and violence, to try and deepen his implications.

The author’s ambitions may well be more than such a slight narrative can convincingly convey. The plot of The Paper Men is the stuff of force: Barclay and Tucker are such unequaled fools, such spiteful caricatures, that larger implication simply will not cling to them; they shed profundity the way a Nobel laureate sheds unfavorable reviews. Barclay’s wild mental states–drunken hallucination and amnesia–seem only an easy method of forcing urgency and tension upon a story that is not so much in need of these qualities as of calmness, leisure, and forbearance.

Calmer qualities of narrative would allow readers to gain some affection for Barclay and Tucker; and that would be the last thing Golding would desire. Burgess and Golding share a need to shape their literary figures as shallowly and distastefully as possible.

Why is it so common a practice in fiction to portray writers as singularly unattractive figures? D. H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, Sir Walter Scott, Thomas Mann, Dickens–the list is a long one indeed of authors who denigrate their own fictional writers. One is hard put to name authors who treat them benevolently. (Trollope, per haps, andBalzac.)

In the books at hand there is a nettlesome pudency about the vocation of writing, perhaps because the books are concerned with literary figures. If one thought–with deliberate naivete, as Wilfred Barclay does–that writing was at one remove from reality, then writing about writers would be at a second or even a third remove since writers would have to be flimsy, unreal creatures, “papermen.”

This is nonsense, of course. A writer is as real a person as a tax auditor or a beautician. He has as many character faults as they, and it is unlikely that he has more. Yet fiction writers are necessarily moralists, and it is the curse of the moralist that he must begin by looking at himself in that cold light in which no one looks good. But to express so much raw self-disgust marks a failure of nerve; the stringent dispassion has been lost. If Enderby and Barclay were cobblers or pickpockets, Burgess and Golding would be much more forgiving toward them. Such obduracy as is shown here results in an odd mawkishness, and The Paper Men–for all its edgy skill–is at last a self-pitying book.

Leave a Reply