As if we needed more proof of the threat to national sovereignty, there comes John Gardner’s latest “James Bond novel,” SeaFire. Gone is Ian Fleming’s wonderful cast of characters. The drab but lovable Q has been replaced by a woman nicknamed Q’ute; the admiral M has been replaced by a committee of bureaucrats; a primping tart called Chastity Vain has taken the place of Bond’s faithful and dignified secretary Moneypenny; and Bond, with knee bent before the altar of the pink ribbon, has stopped philandering and is about to settle down and marry again, which I suppose is preferable to seeing Bond wait anxiously for the results of his latest blood test.

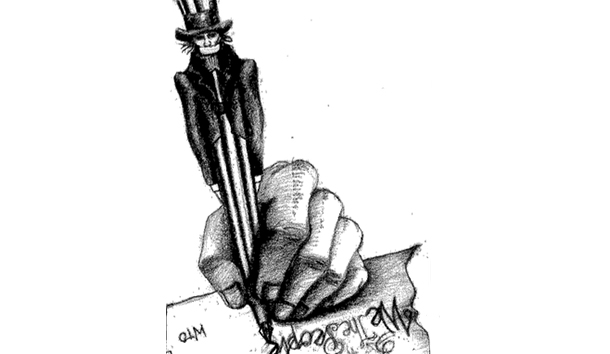

This is not the Bond of Ian Fleming, the cultivated hero whose courage, self-reliance, and resourcefulness saved Britain, protected its security and sovereignty, and defended the institutions of the free and civilized Western world. No, this new Bond has a different purpose. The famed 007 section has been disbanded, and Bond now heads a department called the Two Zeros, which in turn reports to a committee called MicroGlobe One, whose purpose is not to defend Britain’s borders and protect its liberties but instead to fight breaches of international law and treaties. Forget that signature line of identification: “Bond, James Bond.” For it is now: “Bond, Boutros Boutros-Bond.” If this means that the classic Bond films are to be remade as well, to conform with the transnational New World Order, we can only hope that Janet Reno will be cast as Rosa Klebb.

Most telling, however, is this novel’s portrayal of the so-called villains of today and rogues of tomorrow: namely, men of the right. In SeaFire, the villain is one Max Tarn, an English philanthropist who is secretly a German seeking to become—what else?—a new Hitler. Tarn, we are told, “deals in death,” meaning he sells guns; he is against foreigners overrunning Germany; and he has a growing and devout following, some of whom arc hairless. When Bond witnesses a rally in Germany for Max Tarn, he reports: “Thugs, toughs, young men and women, many of the men with their heads shaved, all of them in various kinds of disreputable dress. The kind of louts [who] have made German cities unsafe,” “attacking foreigners,” “parading in the streets,” “marching in antigovernment protests.” In the 1960’s, hellions with long hair and disreputable clothes who took to the streets in antigovernment protests were frequently called “engaged,” and fawned upon for their activism and idealism; today, youngsters with no hair and disreputable clothes who take to the streets in antigovernment protests are called threats to humanity. It must be the hair.

But even more disturbing to Bond and Gardner than the sight of an active populace defending its home and native culture is Max Tarn’s speech, in which Tarn embraces the absurd notion of “a Germany for the Germans.” This, trembles Bond, is Nazism “plain and simple,” because the next step is a Germany for only “purebred Germans.” Bond could almost “hear the jackboots stomping” and see a “Europe a ruin.” as “a montage of terror . . . filled his head: the walking dead of Auschwitz, Belsen,” etc., etc. Never mind that this right-wing rally that Bond witnessed had yet to seize power, had shown no sign of organizing a coup, had built no camps and exterminated no one—never mind, in other words, that this gathering had thus far committed no crime. For Gardner’s and the new Bond’s message is clear: scratch the patriotic veneer of national security, go beneath the surface rhetoric of sovereignty and historic culture, and a scientific racist will emerge.

Why should we worry about a penny dreadful? The obvious answer is that most people are more likely to read John Gardner than Jefferson, more ready to listen to Madonna than Mozart, and more moved by the message on a Greenpeace T-shirt than a principled argument on the dangers of international treaties that would supersede American law for the ostensible purpose of protecting the cute and cuddly. In other words, it is the seemingly innocuous, apparently harmless, often in the guise of humanitarianism, that is frequently the most dangerous to our liberties.

While in Spain last year, I struck up a conversation with a lady visiting from Sussex. She was outraged by Maastricht and European unity. Her husband works in a port that deals in exports of British livestock, a trade which animal rights activists have confounded with numerous (and sometimes violent) demonstrations in recent years, and to what do these activists turn in their attempt to override British law and block her husband’s trade? European law and the World Court. The woman had also, like my wife and I, just returned from bullfights on the Costa del Sol, and we all agreed: Spaniards may believe their national pastime is safe in the short run from the Continent’s organized animal rights movement, but considering the homogenizing force of European consolidation and the New Puritanism sweeping through the West, bullfighting will face the sword in the next century.

Nor did this woman have much faith in John Major’s hard-won “opt-out” option on certain EG policies, such as open immigration as part of the Single European Act. Britain can erect all kinds of barriers to Third World fakirs, she argued, but what is to prevent an Ethiopian or Algerian from entering an EG country with a less stringent entrance policy for non-EG residents and then relocating to Piccadilly for Albion’s more generous social services? Nothing, she answered. “You can forget ‘this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,'” she fumed. “The Camp of the Saints is our future.”

When my wife and I visited museums in Madrid we once again encountered issues of national rights and international law: mass confusion reigned over who should and should not be charged admission to the state museums. Spain had long waived admission fees for all Spanish citizens, all legal foreign residents in Spain, and everyone under the age of 21. All other visitors were charged a fee, that is, until the European Court of Justice ruled that this ethnocentric law that discriminates against aliens runs counter to the spirit of Maastricht and violates Article 59 that mandates equal access to facilities for all EG members. Maastricht supporters hailed the decision as a victory for equal rights and for European harmony. But if free men and women lose even the right to control entrance to their own museums of their own culture and accomplishments, to preserve and enjoy their historic national pastimes, what possible say can they hope to maintain on the more important questions of life and living, of war and peace, of family and faith?

An unsung American hero who realized the dangers to national sovereignty often posed by the seemingly harmless and benevolent was Frank E. Holman, president of the American Bar Association in 1948 and 1949. Holman was born in Sandy City, Utah, in 1886, graduated from the University of Utah, won a Rhodes Scholarship, and, in contrast to those Oxonians who forsake the scholastic for the inhalational arts, actually earned a law degree at Oxford. He worked in private practice in the 1930’s, opposed Franklin Roosevelt—whom he called early on “a great fake, perhaps one of the greatest in American polities”—and fought against the New Deal and entrance into World War II. After the war, as president of the ABA, and in light of the formation of the United Nations, he fought tirelessly against the dangers posed by “socialist encroachments at home and international encroachments from abroad.” He called for an alliance of the Southern and Western states against the Northeastern internationalists and their allies in the larger Midwestern states, for only this alliance, he believed, could “save us from becoming” a “completely Socialized State at home and a puppet state in a world-wide hegemony.”

The seemingly innocuous ruling that Holman saw as critical to the future of our national sovereignty was the Supreme Court ruling of 1920, Missouri v. Holland. In 1914, a U.S. District Court had found unconstitutional a federal law protecting migratory birds, ruling that it was an invasion of the powers reserved to the states by the Tenth Amendment, for the states had always regulated such matters in the past. The federal government, however, then signed a treaty with Great Britain to protect the birds and enacted statutes to carry out terms of the treaty, which in 1920, in Missouri v. Holland, the Supreme Court upheld because of Congress’s authority to pass all “necessary and proper” laws in order to enact the provisions of a signed international agreement.

It did not take social activists long to understand that the true meaning of this ruling had little to do with the sovereignty of nature and everything to do with the nature of national sovereignty. For unhappy with a law in your particular state, and without the votes and support needed at the state level to overturn it? No problem, simply lobby the federal government to enter into a foreign treaty or executive agreement with an international entity that outlaws the activity you disapprove of, and then the Supreme Court will uphold any and all laws Congress may pass that overturn the activity currently banned in your state. It was exactly this end-around the democratic process that child labor law activists and civil rights workers relied on to fight against state laws they opposed earlier this century, and it is U.N. treaties and the acronymic “trade” pacts on which open-border activists rely today for the supposed “right” of Haitians to invade our shores; to which the ACLU appeals in its attempts to abolish capital punishment at the state level; and to which environmentalists turn to hinder Americans’ right to control their own conservation laws.

What Holman found especially dangerous was the U.N.’s Declaration of Human Rights, which he called a “strange document” that could eventually dictate what does and does not constitute “adequate employment, adequate wages, adequate housing and clothing, and adequate rest and leisure,” if not also authorize “some agency . . . like the World Court to nullify our immigration laws.” He also fought against the signing of the U.N. Genocide Treaty—especially its vague ban on “serious mental harm,” which as we know today could be anything from an argument with your wife to the rolling of your eves at a rude black man at a Denny’s restaurant—and he fought against the treaty not because he was secretly a Max Tarn in favor of genocide, but because it would give the federal government at the prodding of social activists the means to trample state laws and the democratic process as established by the Constitution. So doggedly did Holman fight Eleanor Roosevelt’s push in the 1950’s for legally binding U.N. resolutions that President Eisenhower derided his crusade as one “to save the United States from Eleanor Roosevelt.”

It was Frank Holman’s activism of the late 1940’s that was the driving force behind Ohio Senator John Bricker’s attempts in the 1950’s to pass a constitutional amendment that would prohibit this method of superseding American law. And though there were many versions of the so-called Bricker Amendment throughout the 50’s, all of them generally sought three things: to confine treaties to foreign affairs issues, to ensure that international agreements made by Presidents were not self-executing in terms of domestic law (meaning the judiciary could not overturn state law on the basis of an international agreement alone, without the passage of subsequent legislation), and to protect the constitutional rights and liberties of Americans by ensuring that treaties and executive agreements could not supersede or abrogate provisions of the Constitution that reserved rights to the states.

As we all know, Eisenhower and fellow Republicans succeeded in killing the amendment with ad hominem attacks on its proponents and by distorting the issue to a debate whether the public should be allowed to interfere with the governing of the country’s foreign policy, something the Bricker Amendment and its supporters never advocated. All of the versions of the Bricker Amendment made it perfectly clear that the states would only become involved in foreign policy that dealt with matters historically and constitutionally under their jurisdiction and never in such areas as national defense, military alliances, and control of nuclear weapons, all of which would remain under the exclusive authority of the federal government.

In a 1956 article, James Burnham addressed two important questions that were often posed at the height of the debate over the Bricker Amendment. The first one concerned what our Founding Fathers had to say on this matter. “They understood,” wrote Burnham, that “treaties must be given the force of domestic law. . . . But they never considered the entirely different question of giving the force of domestic law to unspecified actions that would be taken by continuing international bodies [such as the mandatory dispute settlement panels whose decisions America agreed to accept as part of the WTO]. The latter is equivalent to the surrender . . . of national sovereignty in favor of world government. Our Constitution as it now reads does not make the relevant distinction.”

The second question Burnham addressed was whether all of this was much ado about nothing. “Up until a generation ago,” he wrote, “the danger of constitutional subversion via the treaty power. . . could be considered academic. But it is either naive or disingenuous to continue to brush it off.” If Burnham thought in light of the formation of the United Nations, the proposed Genocide Treaty, and the U.N.-sponsored “police action” in Korea that the usurpation of national sovereignty was a real enough possibility to warrant an amendment to the Constitution in the mid-1950’s, one can only imagine what Burnham would have to say today about the future of a people that opens its arms to NAFTA, GATT, and the WTO and that courts such tyrannies as a U.N. standing army and international agreements that would strip them of their control over abortion, immigration, wages, child care, adoption, education, parental rights, firearms, and capital punishment.

But if there are still some among us who believe all of this is indeed much ado about nothing—that this is not the time to demand the passage of a new Bricker Amendment—then please remember what President Clinton surreptitiously proposed in Presidential Decision Directive 25 early last year. Following on the heels of P.D.D. 13 in late 1993, this directive outlined the placing of American soldiers under the exclusive command and control of the United Nations; the sharing of classified information with other countries of the United Nations (the vast majority of whose members queue up annually for American largess and then spend the rest of the year denouncing us as evil incarnate); the repealing of the law that limits the number of troops the United States can commit to United Nations command without congressional approval; and the establishing of a special financial account for U.N. missions that would not need congressional approval. When Congressman Dick Zimmer of New Jersey requested a copy of the executive order, a Clinton aide replied, “We’re not going to release it. We don’t want to be hassled by adverse public reaction.” A President of the United States tries to surrender our country’s sovereignty and to relinquish his authority as Commander-in- Chief, and he does not regard this as an issue for public debate.

Seven days later, servicemen at the Twentynine Palms Marine base in California were given a “Combat Arms Survey” that originated as a result of P.D.D. 13 and 25. When news of the survey’s contents leaked out to the public, the Marine Corps played down its significance by explaining that it was only an academic exercise conducted by a researcher at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey. The survey’s author, however, admitted that he wrote the questions as a direct result of Clinton’s directives and that the administering of the survey was approved by the military and supervised by civilian faculty, including a former Assistant Secretary of Defense. Clearly, from the perspective of officials in government, the military, and academia, none of the ideas in the survey was too offensive or treasonous not to air.

Part One of the survey answered the question of what the best and the brightest might have our military do to justify the billions of dollars it continues to receive in the post-Cold War era, some of which are: security at Olympic and Super Bowl games, fire fighting and flood control, security at state and federal prisons, animal control and clean-up, road repair, landscaping, and substitute teaching. That’s right, “Be All You Can Be” could possibly soon mean guarding O.J. on his NordicTrack and slinging squirrel skins for the state.

This first section of the survey, however, merely softens the blow of the truly terrifying matter in the second part. Here the marines were asked to check off in the appropriate box the extent of their agreement or disagreement with such propositions as:

—”U.S. combat troops should participate in U.N. missions under U.N. command and control.”

—”It would make no difference to me to take orders from a U.N. company commander.”

—”I feel there is no conflict between my oath of office and serving as a U.N. soldier.”

—”I would swear to the following code: ‘I am a United Nations fighting person. I serve in the forces which maintain world peace and every nation’s way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.'” (Emphasis added.)

—”I feel the President of the United States has the authority to pass his responsibilities as Commander-in-Chief to the U.N. Secretary General.”

—And lastly: “If the U.S. government declared a ban on the possession, sale, transportation, and transfer of all nonsporting firearms, and if after a 30-day amnesty period, a number of citizens had still refused to surrender their firearms, ‘I would fire upon U.S. citizens who refuse or resist confiscation of firearms banned by the U.S. government.'”

None of the above should really surprise us. After all. Vice President Gore has publicly stated that Americans killed in the Persian Gulf War died not for their country but “for the United Nations,” which is true.

When this combat arms survey became public, I phoned a young marine to get his response. He had not taken the survey, but agreed to give his opinion on the above propositions. When I asked him if he would swear an oath not to his corps and to his country but to the United Nations, if he would support a President of the United States who willingly surrendered his constitutional authority as Commander-in-Chief to a Third World disciple of Babalou, if he would storm a private residency and murder an American citizen who refused to register or surrender his legally purchased firearm, he replied calmly and confidently: “I would do as I’m told.”

Though a country certainly needs young men who follow orders, blind devotion and discipline can be as evil as divine, and when I heard the young soldier answer my question with nary a second of reflection, I could not help wondering how John Randolph, Teddy Roosevelt, or Alvin York might have replied. Alvin York overcame his pacifist beliefs when he convinced himself that by killing abroad he would help to bring the bloodshed to a halt. But killing distant Germans during wartime, this is one thing; killing neighboring kin in times of peace, this is quite another. If ever conscientious objectors were needed in this country, it would be each and every time the Stars and Stripes flies in the shadow of the blue flag of transnationalism.

Leave a Reply