Before his trip to Rome in February, Boris Yeltsin promised everyone who would listen that he would personally invite the Pope to visit Russia. Yeltsin frequently rattled on in front of reporters, like a football player still sprinting after he is out of bounds. For example, he claimed that the youngster Clinton was pushing the world toward World War III by threatening to bomb Iraq, a claim not even the most hard-line commie-nationalist Duma deputies had made, seeming to mix up in his obviously confused mind the threats themselves with vague apocalyptic visions of his country remaining a major player in the great game of nations. Sergei Yaztrzhembsky, his long suffering press secretary, frequently stepped in to explain what the president really meant (he didn’t mean to say that Russia would launch a nuclear strike if the United States bombed Baghdad), dodging any questions about how Mr. Yeltsin is feeling or about who, if anybody, is in charge in the Kremlin. The Russian press began publishing Kremlin leaks about Yeltsin losing his grip, about the “Father of Russian democracy” working only a few hours a day if at all, and about how power had fallen into the hands of Yeltsin’s ambitious daughter, Tatyana Dyachenko (named a presidential advisor last year), and Yeltsin’s wife, Naina. Naina and Tatyana themselves are reputedly under the sway of a charismatic family advisor, a banker-media-oil magnate with a shady past, onetime Security Council Deputy Secretary, and unofficial Russian envoy to Chechnya—Boris Berezovsky (named by Forbes magazine as one of the world’s richest men and portrayed in the same magazine in 1996 as the Godfather of the fused Russian Mafia-government-business structures).

Cut to Davos, Switzerland, in January of this year: the annual “World Economic Forum” at the Alpine ski resort was a conspiracy theorist’s nightmare come true. Here, the rich and powerful from government, media, and big business gather to plan the next stage of globalization. George Soros hobnobs with William Safire, and European bigwigs mingle with Russian semi-gangster predprinimateli (“entrepreneurs”). Boris Berezovsky attracts the most attention of any member of the Russian contingent, as he has in recent years. Eclipsing his ally (then Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, whom Yeltsin fired in March) as well as his enemies (First Deputy Prime Minister Anatoly Chubays and banking mogul Vladimir Potanin), Berezovsky basks in the glow of the media limelight. The forum is excited by rumors that Berezovsky intends to gather the Russian financial oligarchs for a conference on peace (since last summer, the oligarchs have been warring over the privatization of the remaining tasty morsels of the Russian economy) and on the future of Russia. Berezovsky himself declares that the oligarchy should unite ahead of the 1999 parliamentary elections and the 2000 presidential campaign as they did in 1996, when he forged a fleeting alliance behind Yeltsin’s re-election and, with all the tools (both legal and illegal) available, saved Russia—and the oligarchic clans—from the communists. “We came,” intones the banker-cum-kingmaker, “to rest and negotiate.” He is clearly enjoying the role of international celebrity.

Unspoken, but clearly on the minds of the elites, was Yeltsin’s obvious physical and mental deterioration (evidenced most dramatically at his meeting with Jacques Chirac and Helmut Kohl on March 26, when Kohl had to coach Yeltsin on what to do next) and its implications for the clans themselves. Without Yeltsin as a buffer, the clan chieftains might break their unwritten code and shed each other’s blood. The possibility of Yeltsin’s senility or, worse, his demise, had greatly concentrated the oligarchic mind. The old man’s deterioration had raised the stakes of the intra-oligarchy clan feuds. True, assassination of lower-level “businessmen” or nosy journalists has become common enough—the spate of contract killings of Moscow “businessmen” in the last few years testifies to the ruthlessness of the Russian “sharks of capital”—but none wants open warfare. More worrisome was the murder last fall of St. Petersburg privatization chief Mikhail Manevich, a close friend of Chubays, shot by a rooftop sniper as he drove down one of St. Petersburg’s main avenues. Did Berezovsky, overcome by hubris, certain of Yeltsin’s continued backing, have Manevich killed as a last warning to Chubays and Potanin? After all, Berezovsky himself was the target of a failed contract hit a few years ago, before the rules of the game had been established. Nevertheless, even media outlets controlled by Berezovsky, which include the gigantic state TV network, ORT, appeared to concede that a lasting peace appears unlikely: Potanin and Chubays were not jumping on Berezovsky’s bandwagon. The post-Davos line was that the Berezovsky-linked clans have tapped Chernomyrdin as Yeltsin’s heir —for now, at least (Chernomyrdin’s dismissal in March was interpreted by some as a sign that Berezovsky had freed his ally from the burden of the prime minister’s post so that he could concentrate on the upcoming elections, while others concluded that Berezovsky himself might be losing influence). Potanin and Chubays may be looking for a Yeltsin heir of their own. Such is Russian reality.

That the Russian press is now openly writing about what everyone in Moscow already knew indicates the truth in the rumors: Yeltsin is senile; he is tired; he never really recovered from the exhausting 1996 presidential campaign and the open heart surgery that followed it. What’s more, Yeltsin’s health problems are aggravated by his decades of heavy drinking. Moscow elites are now beginning the hunt for his successor, or at least planning ahead for the swiftly approaching post-Yeltsin era, something they would not have dared to do—Kremlin contacts remain quite important in post-communist Russia—if the old man were still in charge. Moreover, Berezovsky’s role, his special links with the “family” (which includes blood relations and a few apparatchiks close to the Yeltsins), is no longer off limits in the Russian media. And shades of Russia’s past are haunting the collective mind of Russia. Has this all happened before? This fantastic little man with the rapid-fire speech, impressive intellect (a mathematician and “systems analyst,” he is a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences), charismatic persona, and effortless energy—is he Yeltsin’s Rasputin?

In Nicholas and Alexandra, a dissection of the family dynamics that lay at the heart of Kremlin politics under Nicholas 11, Robert K. Massie recounts a bizarre meeting between reformist Prime Minister Pytor Stolypin and a certain wild-eyed Siberian faith healer: “He ran his eyes over me,” remembered Stolypin, “mumbled mysterious and inarticulate words from the Scriptures [and] made strange movements with his hands. . . . I did realize that the man possessed great hypnotic power, which was beginning to produce a fairly strong moral impression on me. . . . I pulled myself together.” What Stolypin did not know at the time was what would come of the strange encounter with Grigori Rasputin, debauched starets, or holy man, who had won the confidence of the Imperial family—or at least of the Empress Alexandra Fedorovna, who judged Rasputin capable of healing her hemophiliac son, Alexis, heir apparent to the Romanov throne. Rasputin informed the Empress that Stolypin had seemed inattentive—he had resisted Rasputin’s hypnotic stare—and that the prime minister, a man whose reforms were just beginning to revitalize a moribund Russia in the fateful period before the Great War, did not appear to be chosen by Cod to lead the Russian government’s ambitious reform program. Thus did Rasputin “take the empire,” according to British physician J.B.S. Haldane, by “stopping the bleeding” of Alexis. Rasputin was deemed by some to be the author of the empire’s decline. This certainly sealed the hairy, caftan-draped figure’s fate: he was eventually murdered by a group of concerned Russian nobles. The damage, however, had been done.

Tales of Rasputin bringing about the dissolution of the empire are greatly exaggerated. Nevertheless, the malevolent influence of this hypnotic opportunist stifled Russian reforms and contributed to the debacle that would come. In fact, some courtiers considered him a German spy during the war years— Rasputin had taken to giving advice to the Imperial family on military as well as political matters—and the setbacks suffered by Russian arms only convinced those opposed to his influence that Rasputin was destroying Russia. His opponents (like Chubays and Potanin in their intrigues against Berezovsky) even won small, temporary victories against Rasputin: the holy man was twice ordered out of St. Petersburg, but he soon returned. Rasputin, it was plain, was giving something to the Romanovs that no one else could. In the true tradition of the Russian starets, all the Siberian fakir brought with him to the parlors of St. Petersburg was his commanding persona and the appearance of an ability to satisfy the desire of a loving and faithful wife and mother to secure the future of her long-suffering son and his simple-minded father. Rasputin, despite the intrigues of those who feared his influence, retained the family’s confidence.

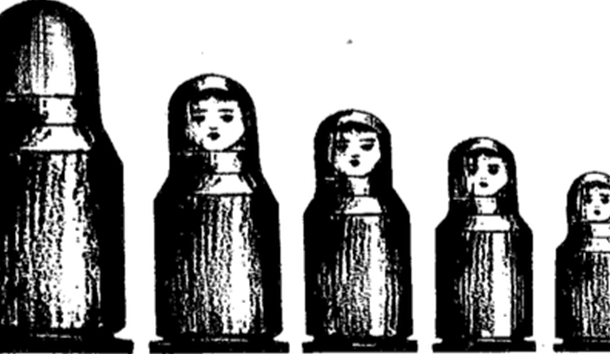

“History always repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” This aphorism is much on Russian minds these days, as anyone who has seen the popular Russian TV program Kukly (Puppets) can certify. The puppets’ dead-on impersonations of well-known public figures satirize Russian reality (within certain limits, since the program has attracted the unfavorable attention of the Kremlin on certain occasions), readily mocking the Kremlin’s palace intrigues, as Byzantine as any under past rulers, imperial or communist. Yeltsin is increasingly portrayed as a doddering, indecisive figure, badgered by his wife and daughter to follow this or that policy and increasingly under the influence of Berezovsky, who uses his access to the faltering, easily manipulated president to move against his enemies. Judging from the ups and downs of Berezovsky and his enemies in recent months, as well as Yeltsin’s erratic behavior and the sordid tales once leaking, now pouring, from the Kremlin, the picture Kukly presents is close to the true state of affairs atop what Russians call the “political Olympus” on the Moscow river.

The newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets has been frank about the parallels between the Romanov’s dependence on Rasputin and the Yeltsins’ rumored dependence on Berezovsky. An article from February, written as a mock soap opera script, portrays Yeltsin as henpecked by his wife and his strong-willed daughter. Lurking in the shadows is the dark, weasel-like figure of Berezovsky, portrayed as a malevolent charlatan with a particularly strong hold on Naina and Tatyana. The paper is not shy about casting Berezovsky as the stereotypical conniving Jewish financier of legend and many a conspiracy theory: he is identified as the family’s confidant and advisor (Berezovsky is widely believed to be building a nice nest egg for the Yeltsins, probably by investing recycled state funds in foreign banks and business enterprises via Yeltsin’s son-in-law, who heads the airline Aeroflot), but also, tellingly, as an inorodets, an alien, a much stronger word than inostranets, foreigner. In the Moskovsky Komsomolets satire, the Russian reading public could not have missed the obvious parallels between the simple-minded Nicky and the senile Boris, the strong-willed Alexandra and the domineering pair, Tatyana and Naina, or between the hypnotic influence of Rasputin and the apparent power of Berezovsky. Even the crude “alien” charge invokes collective memories of Stalin unearthing plots by “rootless cosmopolitans” and of Czar Ivan III unmasking the court physician. Master Leon the Jew, who allegedly was planning the medical murder of Ivan’s son and heir.

This mock soap opera was the most serious attack on Berezovsky in the Russian press up to that time, though the 52-year-old businessman and power broker seems, at this juncture, stronger than ever. Stronger, but not invulnerable, for the tale of Boris Berezovsky involves the whole of the transition of Russia from communism to what critics have dubbed “robber capitalism,” which may be close to exhausting its potential for development by exhausting Russia.

The financial oligarchy that shares power in the Kremlin today is built around the “industrial financial” groups that have sprung up from what is left of the old Soviet financial and industrial ministries. Among the myriad strata of loosely connected “elites” are both new and old oligarchs who seized control of financial institutions and the Russian industrial base in the transition period from the late 1980’s to the early 1990’s. The old oligarchs are ex-Soviet ministers, plant directors, and industrial branch managers. During the initial phase of economic reforms in the late 1980’s, they became “businessmen,” managers and often stockholders (or at least trustees for managing state shares) in revamped industrial enterprises. The most important—and lucrative—of these are involved in extractive industries, particularly in oil and gas. The most prominent “old” oligarch is Chernomyrdin, whose base is the gas monopoly he built, Gazprom. The new oligarchs tend to have made their mark as bankers, either using state connections (Berezovsky’s partner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, worked in the Komsomol, the communist youth league) to gain a foothold in banking, or making their fortunes in shady business deals (the import-export business and financial pyramid operations proved lucrative for many aspiring oligarchs, including Berezovsky) and then quickly buying into banks.

The particular attraction of the banking industry is not difficult to ascertain. First, as state financial institutions were transformed into joint-stock companies, those who could secure a foothold in the fledgling banking industry gained access to the foreign currency reserves of the former system. With banking laws as yet uncodified, opportunities for plunder readily presented themselves. Second, by making sweetheart deals with Kremlin apparatchiks, the newly minted bankers were often granted “authorized” status, meaning that they were authorized to handle the accounts of certain still very productive state enterprises, such as Moscow’s state-run arms sales agency. Third, when then privatization guru Anatoly Chubays began the process of privatizing huge state conglomerates, such as the telecommunications monopoly Svyazinvest, he made sure that “authorized” financial concerns won the auctions (it was the dispute between Berezovsky and Potanin over just who had been “authorized” to win the Svyazinvest auction that sparked the “bankers’ war” in the first place), thus securing influential financial interests as his backers in Kremlin power games. Finally, by plundering state coffers and arranging insider deals with state officials, the new oligarchs became wealthy enough to branch out, buying up newspapers and television stations (for propaganda purposes) as well as oil companies and metallurgy concerns.

The new oligarchs were now strong enough to deal face-to-face with the “old,” even to outstrip them in wealth and influence. By 1996, Russians spoke of a semibankershina (“rule of the seven [largest] banks”) dominating Russia, an oligarchy headed by kingpins Berezovsky, Potanin, Khodorkovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, Pyotr Aven, Mikhail Fridman, and Vladimir Smolensky. The “rule of the seven banks” ensured Yeltsin’s re-election. Berezovsky, the unofficial first among equals of the banking oligarchy, engineered the campaign himself, with help from Tatyana, then publicly emerging as a power in her own right, and Chubays, then in tight with the seven strongmen. But the Svyazinvest row and the “bankers’ war” spoiled the oligarchs’ carefully laid plans and left the door open for some very unpleasant warfare in the oligarch-controlled media: six of the seven bankers are Jews. Potanin, all but cut out of Kremlin insider deals since the flare-up of the “bankers’ war,” is a Russian. But Berezovsky at one time held an Israeli passport (he claims he no longer does); Gusinsky, a leading figure in the World Jewish Congress, has bragged (on Israeli TV) of the power of the “Jewish lobby” in the Kremlin; and other leading Jewish bankers are rumored to hold foreign passports.

Their enemies have not let this opportunity slip past them. Potanin’s newspaper, Russky Telegraf, occasionally drops not-so-subtle hints that Berezovsky’s loyalty to Russia is, well, questionable. Berezovsky, for his part, has gone to great lengths to depict himself as devoted to Russia and defending Russia’s national interests. He is even said to finance certain “patriotic” organizations as a sort of insurance policy for him and his allies, and he has clearly aligned himself with hard-liners like former Internal Affairs Minister Anatoly Kulikov, who commanded ground forces in the disastrous Chechen campaign, and the stodgy apparatchik, Chernomyrdin. Berezovsky’s insurance policy may prove its worth in the near future.

The end game may have been foretold by the inclusion of Boris Nemtsov, formerly governor of the Nizhegorod region, a showcase of economic reform and relative stability in the Russian heartland, in the government in the spring of last year. First Deputy Premier Nemtsov, not yet 40 years old, is an outsider and Kremlin neophyte who espouses what he calls “people’s capitalism,” a program influenced by his political advisor, Viktor Aksyuchits, a Solzhenitsyn-inspired political philosopher and leader of the center-right Christian Democratic Movement. “People’s capitalism” is a melding of Russian social traditionalism with “Westernizing” ideas of decentralization —including a distributist-oriented economic decentralization. Along with quintessential outsider Aleksandr Lebed, who espouses a remarkably similar political-economic line, and Duma faction leader and economist Grigory Yavlinsky, who designed Nemtsov’s successful regional economic program, Nemtsov shares a reputation for honesty and integrity that is a rare commodity in Russian politics. Popularity polls consistently rate Nemtsov and Lebed at or near the top of the charts, and Yavlinsky, long hampered by a policy-wonk image, appears to be gaining some ground as well. Moscow is rife with rumors of a Lebed-Yavlinsky alliance, and Nemtsov’s long association with Yavlinsky appears to make him a possible coalition partner, though the trio’s personal ambitions make the formation of such an alliance problematic. A populist alliance, of course, would be the oligarchy’s worst nightmare: Berezovsky’s media outlets have attacked Nemtsov and Lebed with abandon in recent months, and efforts by the Kremlin Svengali to co-opt the oligarchy’s most dangerous opponents have so far failed. Nemtsov advisor Aksyuchits has called Berezovsky “a source of evil in Russia,” and Nemtsov, Lebed, and Yavlinsky continue to rail against “robber capitalism” and the “semi-criminal oligarchy,” much to the delight of a jaded and long-suffering electorate.

But the possible rise of a populist coalition is only part of the rain that is already steadily falling on Berezovsky’s parade. In January, signs that the Russian social-economic crisis might be approaching critical mass began to appear: miners in Vorkuta held enterprise managers hostage for a time, demanding payment of back wages (protests appear to be intensifying over unpaid state wages and pensions—about 40 percent of the country’s industrial base is still state-owned); state foreign currency and gold reserves, used liberally in recent months to prop up the faltering ruble and finance government expenses, are rapidly dwindling, creating fear of a devaluation of the ruble and possible rampant inflation; foreign investors—a vital source of income for an all-but-bankrupt state treasury—appear to be pulling out of Russian securities markets, despite the temporary raising of interest rates on short-term government paper from 28 to 42 percent (the short-term nature of the securities is draining the Russian treasury almost as fast as investors can fill it); capital flight continues; oil prices on world markets have been on the decline recently, hurting one of the few profitable Russian industries (a devaluation of the ruble would do Russia little good because Russia depends on raw material exports, not finished goods, as a source of trade-generated income); the economy continues to stagnate; and the Kremlin appears headed for yet another round of intra-oligarchy infighting, further delaying critical economic reforms as the various interests maneuver to snatch up more property scheduled for privatization at fire-sale prices. Despite all of this, the clans still appear to be more concerned with seizing wealth than creating it.

Berezovsky has taken the recent spate of bold attacks on him in Moskovsky Komsomolets (controlled by Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov, the Richard Daley of Russia) and in Potanin-controlled media quite seriously, seeing them as part and parcel of a Potanin-Chubays-Luzhkov plan to blame any financial collapse on a cabal of Jewish bankers headed by a latter-day Rasputin (in a March press interview, Chubavs actuallv compared Berezovsky with the Siberian shaman). In fact, Berezovsky’s media outlets appear to have taken a page from the Potanin-Chubays notebook: one Berezovsky-financed newspaper recently claimed that the financial crisis is being engineered by Chubays and George Soros as part of a plan to finish off Berezovsky and friends once and for all. Moreover, there are signs that law enforcement agencies—long influenced by Berezovsky- may be interested in finding out just who ordered the contract murder of Russian TV executive Vlad Listev in 1995 (most savvy Muscovites know that Berezovsky was behind this). Berezovsky and his cronies do appear quite vulnerable. In March, Moskovskaya Pravda, another paper tied to Luzhkov, upped the ante even further: a former KGB officer accused Berezovsky of being a Mossad agent. If a collapse does occur, then Berezovsky’s head could very well wind up decorating the Kremlin wall—if his Israeli passport is not in order, that is, and if the West does not come through with more IMF and World Bank cash to keep the whole bloody mess running. (I am reminded of a Gorbachev-era political cartoon depicting the hapless Gorby at a bank teller’s window marked “IMF,” his gun pointed at his own temple. He warns, “Give me the money, or I’ll shoot!”)

Americans would do well to think of Russia not as some sort of political freak show but as a distant mirror. American workers whose jobs have been shipped to Mexico or Asia as a result of “free trade” deals made between monopolists and bureaucrats might believe that the Russian oligarchy is hardly in the same league with our own. Those of us who have followed the Clinton saga might think the Yeltsins to be less corrupt than the Clintons. How can a government in hock to China via the Lippo Group, or one that kowtows to the interests of Israel and Saudi Arabia, a government headed by a chief executive neck deep in vice and scandal, have the nerve to preach to the Russians about good government and reform? To paraphrase George McGovern, come home America. We may find that we have our own Rasputins to root out.

Leave a Reply