The latest election cycle did not deliver happy results for the political right. Our dismay is compounded by the strong impression of an unfair result.

Whatever you think of the integrity of last November’s elections, it cannot be denied that in the months prior a great many very big thumbs—Wall Street, Silicon Valley, the academy, well-nigh all of the media—were pressing down on Joe Biden’s side of the scales; so much so that Biden did essentially no campaigning. The Big Thumbs did his campaigning for him.

So now we have a Democrat in the White House and Democratic majorities in both chambers of the federal legislature. This, at a time when the Democratic Party is dominated by a radical progressivism more extreme than ever before in U.S. history.

The election results weren’t all bad. Republicans actually gained 14 seats in the House of Representatives; not enough for a majority, but heartening nonetheless. They made significant gains at the local level, too. The party won “trifecta” control—holding the governorship and both legislative chambers of a state simultaneously—in two more states, expanding their lead to 23 such states against the Democrats’ 15. The Democratic domination of the federal executive and legislature left the strongest impression, though, so we on the right are naturally in a low mood.

Cheer up, fellow conservatives. Say not the struggle nought availeth! We have, after all, been here before. Dramatically so even, in 1964, for instance, when Democrats took the White House by a landslide and attained veto-proof majorities in both houses of Congress.

That political setback united and fortified the intellectual right. As George H. Nash put it in his book The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America (1976):

The feeling was in the air: the phase of consolidation, the years of preparation, were ending. Conservatives were less and less intellectual pariahs. In 1964, Nelson Rockefeller and the “liberal establishment” told conservatives that they did not belong to the “mainstream” of American life. Four hectic years later, these same conservatives helped capture the presidency of the Unites States.

The conservatism of 1964 of course differs in important ways from that of today. The lesson is a sound one, though: following defeat, we should regroup, reform where necessary, and unify.

Other contributors to this issue of Chronicles suggest particular areas for reform. It is my intent to tackle one of the stickiest: race. In an American context this means, to a good first approximation, issues of black and white.

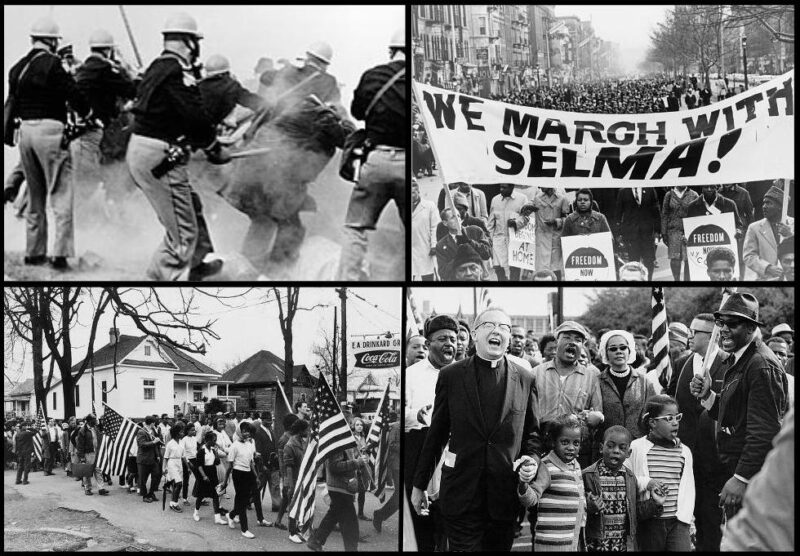

Race was of course on the political agenda in 1964, as America was in the throes of the civil rights revolution. That was the year of the Freedom Summer in Mississippi and of the Civil Rights Act itself. Martin Luther King, Jr. had marched on Washington the year before; the following year saw the Voting Rights Act and the Bloody Sunday March in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery. Race was the premier domestic issue in 1964 America.

Race was of course on the political agenda in 1964, as America was in the throes of the civil rights revolution. That was the year of the Freedom Summer in Mississippi and of the Civil Rights Act itself. Martin Luther King, Jr. had marched on Washington the year before; the following year saw the Voting Rights Act and the Bloody Sunday March in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery. Race was the premier domestic issue in 1964 America.

Blacks labored under obvious social disabilities. White supremacy was a real thing then in many parts of the country, with Jim Crow laws, restrictions on voting rights, and limited access to impartial justice. These disabilities aside, there was widespread anti-black feeling among whites, with much reluctance to associate with blacks.

The civil rights revolution outlawed white supremacy and accelerated changes in the nation’s culture that, in following years, brought any kind of negativity towards blacks under strong social disapproval. The word “racist” began to acquire the overwhelmingly massive pejorative weight it has today, and the phenomenon we now call “virtue signaling”—insincere, cost-free gestures of solidarity with blacks—commenced its career as part of the standard behavioral repertoire of middle-class white Americans.

Most white Americans at the time, along with well-wishers in other countries (I was a college sophomore in 1964 London), assumed that after these laws had been in effect for a few years—or in a worst scenario, perhaps as long as a generation or two—black Americans would rise to full equality of attainment with whites.

•

The two biggest areas in which American blacks and whites differed statistically in 1964 were crime and cognitive test scores. Both differences were longstanding. The high levels of criminality and other social pathologies—drug addiction, illegitimacy—among blacks had been noted by W.E.B. Du Bois in his study of 1890s Philadelphia; intelligence testing of military conscripts from World War I onwards had shown large, consistent gaps between blacks and whites, with, blacks having lower mean scores.

Both these statistical differences were widely supposed to be the result of unjust laws, anti-black prejudice, poverty, and lack of opportunity. The reforms instituted from the 1960s on would, or so it was assumed, allow American blacks to rise to an equality of achievement with whites. The gaps in criminality and test scores would close. We would eventually function like monoracial countries such as Japan, and the whole tiresome business of race would cease to have any importance.

Now, two full generations from 1964, black-white differences in criminality have shrunk only somewhat. The difference remains stark, and the achievement gap in test scores has remained large and fixed over the past few decades. Fifty-seven years of affirmative action and trillions of dollars spent on social programs, together with radical transformations in the attitudes and manners of white Americans, have made very little difference to the statistical outcomes for black Americans in these key areas.

Thinking back on my own enlightened attitudes in 1964, I call what resulted The Great Disappointment. It has wreaked havoc on America’s national psyche, as disappointment will do (think of Charles Dickens’ Miss Havisham in Great Expectations). Hence the bizarre hysterias and weird inversions of reality we have become accustomed to: rich black celebrities lecturing us on “white privilege,” U.S. Senators draped in kente cloth genuflecting to anarchist mobs, “mostly peaceful protests” that leave city centers looted and burned, periodic national panics because some white person has uttered the Deplorable Word—a word under religious-strength taboo for whites, yet a common term of address among underclass blacks.

What explains the Great Disappointment? The current range of opinions is wide.

At one extreme is the acceptance of human biodiversity. According to this point of view, the different human races present different statistical profiles on all kinds of heritable characteristics for the same reason that different breeds of animals—such as dogs and horses—do: localized large-group inbreeding through many, many generations. Since behavior, intelligence, and personality are all to some degree heritable, the theory is that the above results simply follow along.

At the other extreme of the opinion range is critical race theory, which argues that the apparent intractability of black-white statistical differences is caused by persisting anti-black prejudice on the part of white people, otherwise known as systemic racism. Under this theory, whites somehow manage to keep blacks disproportionately down, even as the nation is full of black authority figures: teachers, cops, doctors, athletes, mayors, police chiefs, cabinet officers, a former president, the current vice president.

At the other extreme of the opinion range is critical race theory, which argues that the apparent intractability of black-white statistical differences is caused by persisting anti-black prejudice on the part of white people, otherwise known as systemic racism. Under this theory, whites somehow manage to keep blacks disproportionately down, even as the nation is full of black authority figures: teachers, cops, doctors, athletes, mayors, police chiefs, cabinet officers, a former president, the current vice president.

In between these two extreme positions is a middle zone that I have called “culturism.” The causative factors of the differences between races, according to culturism, are the customary, habitual ways of thinking and behaving in some close-knit social group. The upstream variables here are just history and geography, nothing biological. As a culturist friend explained it to me: If we could just get black Americans thinking the right way, the gaps would disappear.

Which is the right way to think, according to the culturists? I guess it must be to think like white Americans. Better yet, surely, would be to get both black and white Americans thinking like Asian-Americans, who have lower criminality and higher mean test scores than both.

Conservatives have, for the past 50 years, been race-shy, with a very strong preference not to talk about the issue at all. When silence is not possible—for example, after heavily-publicized events with a strong racial component, like the mid-’90s trial of football star O. J. Simpson—critical conservative commentary has been limited to fine points of general jurisprudence.

The reasons for this are easy to understand. The civil rights revolution wrought great changes to America’s culture and laws. Christopher Caldwell has argued in his recent book, The Age of Entitlement, that even our Constitution, or at any rate our understanding of it, was transformed by the civil rights movement. Those changes were resisted by conservatives. Of course they were! That’s what conservatism means: skepticism towards great social changes.

In the political arena, that resistance was denounced by progressives as a defense of the pre-Civil Rights Act order, of legal segregation and voting-rights abuses. In some cases, in the early years of the civil rights revolution, that’s what it was. Those cases were always in a minority, but that didn’t prevent all conservatives being tarred as the faction of white supremacy, wanting to keep blacks down.

The tar has stuck even though white supremacy has long since disappeared, along with any desire for it among conservatives. To the best of my knowledge there is nowadays no such thing as white supremacy. I have been mingling with American conservatives of all kinds for 30 years, including many who would be—and in some cases actually have been—banned from social media on charges of “white supremacy.” None of those labeled as supremacists want to be supreme over blacks, to rule or dominate them from a position of legal privilege.

Among those who call themselves “white advocates,” the most extreme position I have encountered is white separatism—the desire to live apart from blacks. Whatever you think of that, it is not a yearning for supremacy, unless Webster’s Dictionary is lying to me.

The tar of these unjust labels still sticks, though. Hence the race-shy posture among conservatives. For Republican politicians at large, “shy” is too mild an adjective. They practice a style of obsequious race deference that is often acutely embarrassing, always ready with a gushing tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr., always keen to jump on the bandwagon of outrage when a black hoodlum dies while resisting arrest.

•

What is to be done?

My reform recommendation for American conservatives in the 2020s is that we should conquer our shyness about race and speak more boldly, in a way that great numbers of our fellow-countrymen can assent to.

That does not mean we should preach human biodiversity and race realism, which is too strong a medicine for most citizens. Even if human biodiversity gave a true account of reality, it is too much at odds with common sentiments and Americans’ longstanding idealization of human equality. It is also too technical for most people. Forty percent of Americans reject the foundational axioms of modern biology; they would not soon accept the mathematical intricacies of population genetics.

However, if the race-realist end of the opinion spectrum is a poor fit for traditionalist conservatism, the other end, where critical race theory dwells, is a target-rich environment for us. There is, as I have said, no such thing as “white supremacy” as a significant factor in our public life, while the notion of “systemic racism” is explicitly anti-white.

It is regrettably true that anti-whiteness has considerable masochistic appeal among whites, as shown by the success of books like Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (2018). Still, it is hard to believe that such a severe psychic aberration can afflict an actual majority. Among working-class whites there is much resentment towards the compulsory seminars in critical race theory imposed on them by employers, and on their children by the teachers’ unions. Large numbers of white Americans bristle to hear their race—their ancestors, their family members—belittled and insulted.

Conservatives can get the attention of fair-minded citizens by speaking against the anti-whiteness of the currently dominant narrative. We can be the anti-anti-white faction.

What, then, do we offer as an explanation for The Great Disappointment? If it’s not Mother Nature holding blacks back from equal achievement with other races, nor white malice, conscious or otherwise, as critical race theory teaches, what is it? I think that when asked we should posit the middle way, the one I call “culturism.”

I must admit I have some issues with culturism myself, and I doubt it can bring about the “equity” that the current narrative demands: equal social outcomes for all races. It is not intellectually preposterous, though. It is not poisonously anti-white, and it does not deny agency to blacks. There is also academically respectable recent literature supporting the culturist viewpoint, such as the recent books Burdens of Freedom by political scientist Lawrence Mead, The WEIRDest People in the World by anthropologist Joseph Henrich, and The Culture and Development Manifesto by Robert Klitgaard, another anthropologist.

Thus armed with plausible intellectual support, conservatives should go forth and do battle with critical race theory. We shall not, I am sure, find ourselves fighting alone.

Image Credit:

A protester at a Black Lives Matter “De-fund the Police” rally in Brooklyn, New York on June 12, 2020 (Photo by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images).