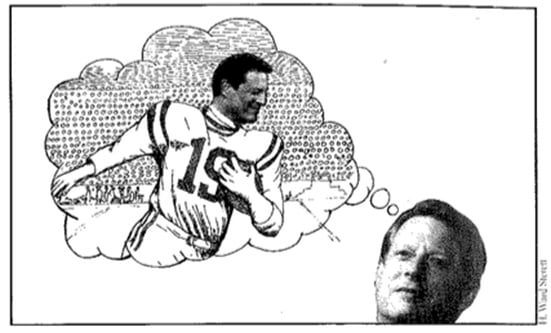

Former Vice President Al Gore distinguished himself by a number of colorful claims, including his invention of the internet, his status as inspiration for the plot of Love Story, and his crime-busting investigations that pulled the covers off Love Canal and the villainy of both the internal-combustion engine and flush toilet. During last year’s presidential campaign, we were treated to lurid tales of his dog’s drinking and drug problems and his uncle’s exposure to tear gas at the battle of Thermopylae. Surprisingly, he never mentioned his historic appearance at quarterback for the 1958 Detroit Lions. Surely Mr. Gore, Renaissance role model for our time and inspiration to Buddhist monks, ballot-recount scammers, and celebrity race-hustlers, would want us all to understand that he, not George Plimpton, got there first. In Gore’s case, each of these grandstanding absurdities was clearly meant to wow gullible members of a particular constituency, including the techno-geeks of Silicon Valley, the literary crowd, and the save-the-schnauzer environmentalists. Why were Monday Night Football enthusiasts not reminded how, fuzzy-cheeked lad often, he came off the bench to relieve the alcohol-befuddled Bobby Layne, tossed the winning touchdown, and began to take shape as his own favorite hero? As outlandish as all this is—and who can tell what other preposterous assertions he may make before we hear the last of him—the problem for ever}’one is that our former Vice Renaissance man thinks all this nonsense should be taken absolutely seriously. For him and for other practicing members of the Society of Ersatz Intellectuals, freedom of speech means never having to say you faked it.

It is not new for those in the public eye—even for those celebrities famous, as media pundits like to say, only for being famous—to fancy themselves experts on a wide range of subjects. In the past, there have been many people eminent in one area who were legitimately knowledgeable about other things. Granted, it is probably too late to determine whether Heinrich Himmler actually made the most spectacular chickweed soufflés in all of Central Europe or whether Russian astronaut Yuri Gagarin really could name the starting lineups for every Major League Baseball team throughout the 1950’s. It is more likely, though, that Gagarin did not know a baseball glove from an oven mitt and, if he ever heard the name “Detroit Tigers,” thought they were a gang of street hooligans who hung out around die corner from the main railway station, wearing black leather jackets, sucker punching the occasional tourist, and strutting their stuff for the girls.

By contrast, Theodore Roosevelt, a genuine Renaissance man, is celebrated in an inscription on the facade of New York City’s Museum of Natural History as “ranchman / scholar / explorer / scientist / conservationist / naturalist / statesman / author / historian / humanitarian / soldier / patriot,” and could claim real accomplishments in all these areas. These are credentials that not even a hard case like Alec Baldwin could truthfully disparage, as he prepares for his move to Paraguay in protest of the Bush administration (and where he may better indulge his enthusiasms for public urination and stoning members of Congress). But for a self-proclaimed expert like Mr. Gore, comparing himself to Jesus, hosting symposia on “metaphor” and tossing off moralistic statements that “evil lies coiled in the human soul,” the satisfaction seems to come from seeing how much he can fabricate—usually out of whole cloth—for special occasions.

Today’s Renaissance celebrity experts are remarkably comfortable with their many versions of themselves. With four or five minutes’ preparation and an absolute minimum of actual knowledge, they are always ready to bob, weave, riff, and pontificate on any number of issues, figuring—rightly—that neither the media nor the general public will check carefully enough to catch them in yet another outrageous pretension. Whether it is Michael Douglas riled up about nukes, or Shirley MacLaine detailing her romps with the Emperor Charlemagne all those centuries ago (they were seen together again last week in Cleveland; this time, there may be photos), or Barbra Streisand—woofers and tweeters cranked up to hearing-impairment volume—claiming to know more about public policy than Sharon Stone, or Toni Morrison lauding Bill Clinton’s performance as the country’s first black president, the famous and foolish have really outdone themselves in recent years.

Some decades ago, Raymond Burr, already well known for his portrayals of such fictitious judicial figures as Perry Mason and Ironsides, was asked by a professional organization to appear and deliver his thoughts on justice. Burr politely declined, reminding them that he was an actor, not a lawyer or prosecutor. More recently, such Renaissance experts as Alan Alda and Ed Asner have appeared at public gatherings to give the attendees the benefit of their vast resources of knowledge on important matters. Alda, without question, used the experience picked up during those hellish years of battlefield surgery on M*A*S*H to instruct those present on erectile dysfunction, public sanitation in Mauritania’s southern provinces, and compulsory euthanasia for the wealthy; and it is reasonable to assume that the cantankerous Asner, still thinking he was Lou Grant, reminded his audience of the importance of insults in headline-writing and what censorship means to people who hate to be interrupted. Someone, after all, must stand tall to proclaim the right of celebrities to preen, trumpet their misconceptions about the world, and behave like oafs in public.

The result is that these are the best of times for self-anointed experts; lately, they have claimed carte blanche to denounce authoritatively the Founding Fathers as racists, boozers, and ne’er-do-wells, and there is an unconfirmed rumor that Jesse Jackson, in a state of the highest dudgeon since Steve Martin, and not Mumia Abu-Jamal, was selected to host this year’s Academy Awards (clearly another example of Selma ’65 racism), will take to the airwaves to “out” President James Monroe, attacking the Monroe Doctrine as nothing but a white-supremacist patriotic ploy to divert attention from the President’s string of Peeping Tom incidents up and down the East Coast. Demeaning the dead really excites these new experts: They can maintain, without fear of contradiction, legal proceedings, or a clout in the eye, that they know for a fact that George Washington often sneaked out of the White House at night to carve “Martha is a strumpet” on the trees in Lafayette Park across the street, and that Thomas Jefferson not only consorted with slaves but pawed coeds and may even have taunted one dancing bear too many during his visits to the National Zoo.

Mel Brooks was obviously joking when, during an interview with critic Kenneth Tynan some years ago, he theorized that Napoleon may have been Jewish because “he was short enough, also he was very nervous and couldn’t keep his hands steady. “That’s why he always kept them under his lapels.” By contrast, Diane Keaton, appearing several years ago at the Academy Awards ceremony in an alarming outfit that made her look like Mao Tse-tung disguised as a food-service worker, appeared deadly serious—and slightly unhinged—as she waxed indignant about what “being normal” really meant. While precise figures are not available from the Bureau of Normal Statistics, it is reasonable to estimate that somewhere between 96.3 and 96.7 percent of the American public have a ballpark idea of what is meant by the term—at least 46 percent of the time. Thus, Keaton’s comments should carry equal weight with Rosie O’Donnell’s antic posturing about gun violence or New York City’s homeless situation (both declining problems for years), or with Jimmy Carter’s infantile apologies for colonialism as, dispatched by the egghead pantywaists in the Clinton administration, he formally handed over the Panama Canal. Perhaps Mr. Carter’s next combat mission will be to storm CIA Headquarters in Langley, ball-peen hammer clutched tightly in his arthritic paw to disable the security system—all the while preaching, with the same ostentatious empathy so often displayed by Bill Clinton, the renaissance qualities of openness and goodwill to impress self-important soul-trolls Susan Sarandon and Tim Robbins and the governing board of Emily’s List.

There are some, like hyper-gadfly attorney Alan Dershowitz or critic Susan Sontag, who seem to fancy themselves experts on everything. With Dershowitz, it is constitutional law, race relations, and presidential perjury, and there will be no stopping him should he attempt the trifecta of Airedale-breeding, the intricacies of literary translation from the Lakota Sioux dialect, and the significance of the loquat in Oriental culture. Sontag, forever in love with the white noise of her own intellect, is known for such extravagant abstractions as “photographers seem to need periodically to resist their own knowingness and to re-mystify what they do”—a comment that must have astounded the ghosts of Margaret Bourke-White, Alfred Stieglitz, and Walker Evans and, were they reminded of it, would terrify Francesco Scavullo and even Sontag’s pal Annie Leibovitz, who might now be forced to reassess their entire careers to make sure they have not behaved badly. Another of Sontag’s authoritative declarations is that the “white race is the cancer of human history,” which sounds suspiciously like the germ of an idea for the second book in her trilogy of definitive philosophical works, perhaps to be tided Arrogance as Metaphor. Other Renaissance experts merely pick one subject, master it imperfectly, and proceed to wing it from then on: All too soon, with his new role on the television sitcom Spin City, we will be hearing from actor Charlie Sheen on the proper distribution of social services, although there may be no truth to the rumor that Katie Couric, berserk with self-admiration after watching (for the 345th time) the videotape of her live colon exhibition on network television, will donate an ovary during an appearance at Radio City Music Hall and, throughout the process itself, ruminate on organ replacement via radio hookup with Larry King.

The thrills of all this are obvious: Where else but in today’s celebrity culture or on the David Letterman Show can a pompous, ill-informed simpleton trot out clownish drivel as Renaissance wisdom and claim—with a straight face —its validity? According to Bill Clinton—a New Democrat and New Renaissance man who feels our pain, remembers nonexistent church burnings in Arkansas from his youth, and did not have sex with that woman—it all depends on “what the meaning of ‘is’ is.” With Letterman, always the entertainer and prankster, we naturally expect such spoofs as his running series of Top Ten lists. The bizarre thing about the new Renaissance experts, however, is that they seem to think they actually are Gandhi, or Albert Schweitzer, or the second comings of Murray Kempton or William F. Buckley, Jr. Such inveterate hams as Alda and Asner conveniently forget that they were reading scripts; they act as if we should believe that they are qualified to perform open-heart surgery or handle a newspaper censorship controversy. More recently, retired newsreader Walter Cronkite—sounding more like Jimmy Carter with each passing day—has spoken out on the rewards to be reaped from one-world government, a concept that cost upward of 100 million lives last century. Today’s Renaissance experts expect the public to accept every benighted proclamation as absolute truth, defying us to question the statements made or the motives behind the foolishness. With these new cognoscenti, what we see is idiotic enough, but what we get is far worse: show-business megalomania and crackbrained New Age psychobabble dressed up as knowledge and reality.

There exists—largely in academia but in danger of spreading like a cloud of marauding Mediterranean fruit flies into the public at large—what might be called the “determination to be weird.” Recent decades have brought ingenious new disciplines such as New Math, whereby two plus two equals 11 (except on alternate rainy Thursday afternoons); a program called “Whole Language,” whose advocates seem to suggest that it is not so important for a youngster to be able to read, write, or spell properly, only that—for purposes of self-esteem—the little tyke take an honest crack at it; and a more recent enthusiasm, only now gaining momentum in the clammy equatorial atmospheres of college faculty lounges, that there is no such thing as objective knowledge. This newest breakthrough promises fabulous potential benefits for mankind down to the bottom quintile of wage earners. Within this postmodern, free-floating structure of reality, academics, lawyers, and other con artists will be able to reeducate the drooling, disoriented masses about how the United States—and specifically the state of Idaho—was responsible for the Cold War, how the roots of modern civilization lie not in ancient Greece, Rome, or Egypt, but in Bangui, squalid river-town capital of the Central African Republic; how Teddy Kennedy really did “dive repeatedly” at Chappaquiddick and Bill Clinton was truthful when he claimed to have “wept uncontrollably” in 1963 while watching Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech on TV. Such transparent fakery is neatly defined by columnist Cindy Adams’ witticism that “the hardest thing for me to believe about the Bible is that there were only 2 asses in the ark.”

Little matters to the Renaissance experts except their own stature. Sadly, our recent leadership has contributed mightily to the blizzard of contrivances presented as reality and good sense, and they have been boosted by the media who, barely into the first Clinton-Gore term, gushed with adolescent infatuation while trumpeting the Clintons’ alleged Renaissance qualities: she, a tireless supporter of childrens’ rights and “one of the top hundred lawyers in the country”—a ranking certified, no doubt, by the Associated Press Coaches’ Poll of top lawyers; he, the policy wonk, still conversant in German from his Rhodes Scholar days and, class guy that he is, reputedly a collector of rare Wedgwood. Thus, years later, the President felt completely free to spin out the canard that “even Presidents have private lives”—and, therefore, they should be given the respect, the free rein, and (of course) the privacy to commit perjury, obstruction of justice, character assassination, even treason as laws are broken, evidence suppressed, critics and opponents slandered, national security sabotaged, and defense secrets passed along to hostile foreign powers for campaign funds.

When writer Mary McCarthy, on Dick Cavett’s television show in 1980, said of rival Lillian Hellman that “every word she writes is a lie, including ‘and’ and ‘the,'” an intriguing precedent was established. Today, given the momentum built up by Bill Clinton as he tweaked the public with falsehood after falsehood while claiming that all has been forgiven and even demanding apologies from others, it may not be long before some wicked commentator amends McCarthy’s provocative declaration to describe our former First Renaissance man as, follows: “Every word Mr. Clinton speaks is a lie, including ‘Bill’ and ‘Clinton.'” His assertions on gun control, school reform, race relations, religion, and partial-birth abortion were the epitome of flagrant duplicity beneath only the flimsiest veneer of historical reality and bipartisan debate. Similarly, Al Gore’s abusive demagoguery over global warming and the Kyoto Treaty—like his self-obsessed post-election “I’ll do anything to win” rallying cry—increasingly resembles the hysteria of a zealot, and one wonders how completely out-of-hand his arguments may get. We must watch closely to see if he begins blaming the dubious phenomenon for such sinister occurrences as the disorder in the Baltimore Orioles’ bullpen, the near-total disappearance of frogs from the third floor of the Old Executive Office Building, and the recent pandemic of print-media misspellings of the words “glyptodont” and “fenugreek.” Now, in the nuclear winter of his discontent, he can proceed in the spirit of bipartisanship to talk up more right-wing conspiracies for the likes of Jack Newfield, Eleanor Clift, Joe Conason, and their block-warden brethren to pursue with fangs bared.

Yet one of the most unpleasant things about modern Renaissance types is that it can be very difficult to get rid of them; once established, they remain on hand, eager to foul the air with foolishness at the barest hint of an invitation. They pretend to master additional disciplines in adjacent areas, assume newer and greater levels of authority, even begin to contradict legitimate scholars. Alan Alda, after his starring role in the hit Broadway play Art, may suddenly turn up at New York City’s Whitney Museum to lecture the society crowd on the brushwork of Renaissance masters Van Dyck and van der Weyden, and visitors will be compelled to wear tiny buttons that read “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be Flemish.” Sen. Hillary Clinton, her customary fever of hubris stoked even higher by the cleverness of her observation that the world must learn to discredit the concept of “another person’s child,” has given signs that, politics and future self-congratulatory memoirs aside, child psychology may be her true calling. In her 1996 book, It Takes a Village—and Other Lessons We Learn From Children, she trotted out a laundry list of specious, pseudo-philosophical platitudes while failing to acknowledge—and then trying to cheat—the Georgetown professor who had done the writing for her. More recently, the former First Lady has asked the nation to buy into allegations that ever)’one is plotting against her (slavering right-wingers, treasonous left-wingers, the entire Washington Redskins’ defensive backfield, all those renegades from the White House’s 1996 “Communication Stream of Conspiracy Commerce” report), that only she is qualified to make proper decisions about serious matters, and—as revealed in an interview in New York magazine last year—that it is impossible to insult her. More ominous, though, is the hint that there should be some sort of roving band of ombudsmen monitoring family life to make sure that America’s little ones are treated with due respect. This, then, is the true aim of today’s Renaissance folks: to impose their views, witless and obnoxious though they may be, on everyone else, friend and foe alike. It is what we should learn to expect from the likes of Bill and Al, Ed and Alan, Diane and Rosie, Susan and The Dersh, Teddy and Walter, and all the others so eager to lecture us, interfere in our lives, and generally bore us to death—and particularly from Hillary, whose book, although a best-seller, was inaccurately titled. It should properly have been called It Takes a Fraud—and Other Lessons We Learn From Phonies.

Leave a Reply