Land of Albania! Let me bend mine eyes On thee, thou rugged nurse of savage men!

—Byron, Childe Harolde’s Pilgrimage

ALBANIAN ANARCHY! BALKAN BLOODBATH! Typical banners to newspaper stories of the riots and virtual civil war that gripped “Europe’s most bizarre country” during 1997, culminating in the forced resignation of Sali Berisha, the first noncommunist president, and the return of seven-foot, gun-toting King Leka I Zogu who threatens to take by bullets the monarchy denied to him by votes. No need for bewilderment. This, after all, is the country in which the villagers of Vilan recently met in solemn conclave to decide if the unusual pregnancy of a mule meant that the devil was in its stomach signaling the Apocalypse.

The gjakmarrja (“taking of blood”) is a centuries-old institution that explains most of the country’s history, recent and remote. In his Eskili, Ky Humbes I Madh (Aeschylus, The Great Loser—yet to be translated into English), Albania’s best-known author, Ismail Kadare, explains the Oresteia’s cycle of family murder and revenge in terms of his own nation’s blood feuds. True, he ignores some differences of principle and detail. In Greece, a death could be avenged by the clan rather than a relative. Compensation might be in goods or labor, or the killer(s) merely cursed and exiled. Albanian rules exclude women, hence no counterparts to Clytemnestra and Electra.

Geography is here a factor. The blood feuds of Albania center on the Northern Highlands—the Rrafsh or plateau—rather than the regions contiguous with Greece, which is one reason for continuing North-South mutual incomprehension and conflict. Still, ancient Epirus (Albania) was identified with bloody vendettas. According to Plutarch’s Life of Pyrrhus (of “pyrrhic victory” fame), “the chieftains and clans of Epirus were perpetually at war because plots and jealousies are natural to them.” His countrymen nicknamed Pyrrhus “The Eagle”; Albanians call their country Shqipëria—Land of the Eagles. Certainly, by juxtaposing Albanian blood-feud regulations with Aeschylean verses, Kadare makes a cogent correlation.

This is an ancient tragicomedy. Albanians did not have a country until modern times, being successively ruled by Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Turks. For centuries, justice meant the fight for freedom from occupation—the home of the brave is the land of the free. The national hero Skanderbeg campaigned for Christian Byzantium against the Turks. In different circumstances, he would have been on the other side— he had converted to Islam before returning to Christianity. Dreams of independence were bound up with language and religion. It is no coincidence that the oldest Albanian texts were written by priests and nationalists to aid Roman Catholic clergy and to pursue the right to be educated in their own tongue, an issue that boiled over in late Ottoman times and remains the dominant one for Albanian minorities in Kosovo and Macedonia. The new country was made fissiparous by its geography, history, language, and religions. Like many another nation, it has a North-South divide based on a river (the Shkumbi), different dialects of the same language (Gheg in the North, Tosk in the South—communist harmonization was less than 100 percent effective), and religion—the North is predominantly Christian, the South Islamic. Hence Northern support for Berisha and violent opposition from the South where communism was also strongest—Enver Hoxha himself was a Tosk. Like Skanderbeg and Zog, Hoxha was basically a bandit chief who forcibly united the land (first liquidating the rival noncommunist and pro-monarchy resistance groups from World War II) and played on national pride in independence and the fear of losing it to either America or Russia. Which explains the endless purges of “traitors” and “polyagents,” most famously the mysterious death (murder? suicide?) of Mehmet Shehu in 1981 (Albania is the only country in which every security minister was eventually denounced and destroyed as a traitor, and in which vinestakes had sharpened points to impale the enemy parachutists supposedly always about to invade!)

One definition of justice in the communist-produced Albanian Dictionary reads, “The sword of the People, by which a traitor is sliced.” Berisha was soon well down this same path, dumping the cofounder of his original Democratic Party, jailing (despite international protests) former Prime Minister Fatos Nano on trumped-up corruption charges, and blatantly rigging the 1996 elections. The extent to which Berisha was involved in the old regime remains obscure—he has naturally rewritten his own history—but he was more continuation than change. Although far from a complete diagnosis, Tirana-based Baptist missionary Glyn Jones’ statement in 1997 gives universal food for thought: “The world’s strongest atheistic government destroyed all personal morality and left a whole nation with hardly any sense of right and wrong. There is a lesson here for any democracy which allows erosion of the moral basis on which its society rests.”

Albanian vendettas are strictly governed by the Great Code (Kanun) devised by the 15th-century prince, Lek Dukagjini. Pope Paul II excommunicated him in 1464 for the code’s “most un-Christian” content. Consisting of 1,263 separate provisions, it was definitively edited and published by the scholarpriest Shtjefën Gjeçovi (1873-1929). Margaret Hasluck’s The Unwritten Law of Albania (1954) provides historical background. Kadare’s novel Broken April (available in English), set in the 1930’s, has for its theme the Kanun and a long-running feud between two village families.

The Kanun covers not only killings but all bodily assaults, disputes over inheritances and land, and theft: “The Kanun was stronger than it seemed. Its power reached everywhere—lands, fields, houses, tombs, roads, markets, weddings—to the very skies whence it fell as rain to fill the water-courses, the cause of a good third of all murders” (Kadare). When Albanians demanded that Berisha’s government compensate them for monies lost in the notorious pyramid schemes, they were reacting in the spirit of the Kanun: recompense is a legal and moral claim. The Kanun punctiliously extends even to the damaging of doors, e.g., if a door is holed by a bullet, the transgressor surrenders his own for the damaged one, which he must forever keep as a reminder. (Hence, in the recent mass vandalisms, the seemingly bizarre removal of doors from other people’s houses.)

Not that all such acts were licit retribution. As Julian Amery, who through his World War II service knew Albanians as well as any foreigner can, writes in his memoir Sons of the Eagle (1948), “They variously proclaimed themselves Fascists, Communists, or Democrats, in obedience to the calculations of interest rather than the dictates of conviction.” Similarly Plutarch on Pyrrhus and company: “They treat the words war and peace as current coins, using whichever is to their advantage, regardless of justice.” We in North America have become all too accustomed to looting being justified in pseudosociological terms.

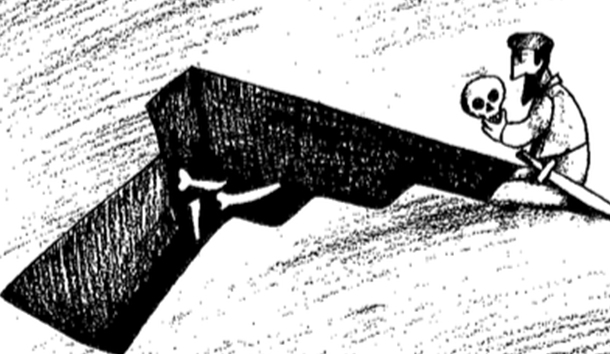

The rules of the blood feud are quite elaborate. Suppose X has killed Y in revenge for the shooting of his brother. This may be a new vendetta, or the continuation of a decades-old—even centuries-old—one. X is now technically a “justicer.” Killings are individual. The Kanun forbids massacres, a factor in the Berisha regime’s failure to execute the top communist officials en masse—nor were any lynched. The ultimate tragedy is the victim who has no family member left to avenge him. There is a special word (one of many to do with blood) for him in Albanian—gjakhupës. X may not have wished to kill Y, but may have been coerced by his father and the sight of his dead brother’s bloodstained shirt fluttering—as prescribed—in the open air, especially if the stains have yellowed, a sign of the unquiet spirit demanding vengeance—very Aeschylean. In the actual killing, X must confront Y with the words “please give my greetings to . . . ” (naming his dead brother), then leave the body face-up, rifle by its head. To omit this ritual is a great disgrace. If overcome by the emotion colloquially known as bloodsickness, X may ask a passerby to perform it for him.

In Lek’s day, stones were used as weapons or carried in races to settle land disputes. When firearms came in, old Albanian pistol butts were commonly inscribed, “When you shoot, it is God who aims.” A ubiquitous communist poster slogan proclaimed, “With pickax in one hand and rifle in the other we are building Socialism.” A local proverb transcends the centuries: “The Albanian response to all challenge—a bullet between the eyes.” Hence their much-photographed addiction to the public brandishing and discharging of guns.

Not all “justicers” are crack shots. The Kanun acknowledges this. If the would-be killer only wounds his target, he may either pay a fine assessed by the village mediator and maintain his vendetta, or not pay and give it up, since the wounded prey is then declared out of bounds. Compensation for wounds is variously assessed: head injuries count twice as much as others; all are categorized by bodily location. Kadare describes a much wounded fugitive who supported his family on monies received, summing up in Marxist terms: “Behind the semi-mythical decor, look for the economic component. As with everything else, blood has been transformed into money.” A genuine flourish: the vampire was one of Marx’s favorite images for capitalism (he used it three times in Das Kapital). The most telling economic aspect was the blood tax, payable by a killer to the regional collector, who recorded such transactions in his Blood Book. This tax played a major role in the local economy. Ledgers speak of good years (many killings) and bad ones (few).

The family of X, the “justicer,” immediately prepares defenses. Male relatives, if prudent, will lie low or leave the community until the truce is obtained. The women are dispersed to other village houses; laws of hospitality compel their acceptance. Women, like the priests of Albania’s three religions (Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim), are exempt from the vendetta. This helps to explain why Hoxha’s widow, Nexhmije, although the first communist luminary to be tried, had her prison sentence quickly commuted, instead of facing a firing-squad as did Elena Ceausescu in Rumania. The Kanun‘s provision for execution of unmarried pregnant girls by their male relatives illuminates the fact that in all of Hoxha’s purges the only female victim of consequence was one Liri Gega, officially a “Titoist agent,” who was pregnant at the time and so deemed a betrayer of the communist family honor as well as her country.

X is now the target of Y’s family, although they may replace him by a brother, an option rarely exercised. A black ribbon, worn on the sleeve, advertises his status as prey. His family will ask Y’s for a 24-hour Besa or truce. This is usually granted. Violation of it, or of any part of the Kanun, is punished. The transgressor’s own family, in concert with the village (led by the Flamurtar or standard bearer)—will burn his house and kill his animals. After Hoxha’s death in 1985, a mobile cadre devoted to maintaining his “teachings” (many bulky volumes, in effect the communist Kanun) was called “Standard Bearers of Enver.”

X must attend Ys funeral and wake, at which he will be neither insulted nor harmed by the male relatives, one of whom is now his own designated killer. A 30-day Besa is now sought and (as usual) granted, although it may be revoked if X is foolish enough to brag of killing Y. X’s family may attempt to save his life by a money payment, determined by an elder called the Blood Master, which is formalized at a meal during which spots of blood are ritually exchanged. This very rarely happens, largely because all males in the victim’s family must concur— one “no” stops it.

Cognate provisions take care of all non-blood disputes, notably land, including absolute bans on moving boundary-markers and any human bones. Ancient historians will think of Solon and Orestes. One swift consequence of communism’s fall was the ripping-up of Hoxha’s tomb and throwing-out of his remains, since he is now beyond the pale of the Kanun—in the new demonology, he is referred to as “The Great Zeus” and as “Vampire” (gjakpirës).

X has two options—he may not (of course) kill his own stalker. He can attempt to flee the community—sections of the local roads are under Besa and so inviolate—and thus escape death. (Escape, however, is often a vain hope. Recently in the lobby of Tirana’s best hotel, a man was decapitated with an ax as the culmination of a vendetta—his killer had spent 40 years tracking him down.) Or he may take sanctuary in a Külla or “tower of refuge” where he may not be killed—only a priest can enter. Female relatives are allowed to bring him food and drink. His sojourn there could be indefinite, and he will not be alone. Kadare has one village where 180 of 200 households are in blood feuds, with almost all the menfolk immured, while Amery reports cases of fugitives holed up for 20 years and more. This aspect of the Kanun is halfway between ancient notions of sanctuary and the modern inviolability (except in Iran) of embassies; this latter code was honored by communist authorities when thousands stormed Tirana embassies in the early 1990’s in quest of legal emigration or illegal flight.

Western writers chorus that one of the Red regime’s (very few) good deeds was its banning of the blood feuds. Its attitude was, in fact, disingenuous to the point of self-contradiction. Thus, the entry on gjakmarrja in the 1985 Party-approved Fjalori Shqiptar (National Encyclopedia) denounces the practice as incompatible with Marxist-Leninism, yet in the previous year Enver Hoxha’s “Speech on the 40th Anniversary of National Liberation” was full of hacking swords, rifles, blood, and the slogan “The Vengeance of the People is Merciless”—his vocabulary that of Kadare and the Kanun. The encyclopedia’s entry on the Kanun, in fact, both has and eats its ideological cake. Lek Dukagjini is pointedly associated with the national hero Skanderbeg, and an unspecified portion of the Kanun is said to typify “the social psychology of the mountaineers and the virtues of our nation: fidelity, manliness, hospitality, courage.” Sections that defend private property, class privilege, and the “obscurantist Church” are denounced as feudal and reactionary. The portions dealing with punishments are noted without blame and this noncommittal conclusion: “All through the Kanun can be seen the distinctive originality of Albania.” Kadare dutifully follows the line: “The Kanun is one of the world’s most monumental constitutions, and we Albanians ought to be proud of begetting it.”

Apart from pretend moral considerations, one respectable reason for suppression was the capitalist aspect of the Kanun. But this was merely an attempted hastening of a decline in killings and revenues in the 1930’s, a phenomenon noted by writers as diverse as Kadare and Amery. The crises of the times, incipient Western influence, and the pre-communist efforts of the much-reviled King Zog to curb the feuds provide coalescent explanations. With war and the invasion of Albania, Zog tiled to impose a general Besa in the national interest because families divided by feuds would not join together against the common enemy and therefore weakened guerrilla resistance. Naturally, there is not one word of this in the communist version.

The more cogent, though unadmitted, impulse was a totalitarian need to take freedom and weapons away from the people; Hoxha wished simply to make killing and revenge a state monopoly. In Kadare’s words, “the Rrafsh has rejected the laws, the police, the courts, replacing them with other moral rules just as adequate, constraining the administrations of occupying foreign powers and later that of the Albanian state, putting the High Plateau quite beyond its control.” Amery found much to approve of in the Kanun: “This ancient code of conduct has undoubtedly exercised a restraining influence on the clansmen and helped to soften the grim realities of anarchy . . . the blood feud has its merits, for it was a great teacher of manners and respect for the dignity of the individual. No Albanian could strike another with impunity, and even schoolmasters had been known to pay with their lives for a hasty cuff in class.”

Whatever one thinks of private justice, after 50 years of communism the vendetta is alive and well—it is no historical curiosity. Despite the efforts of priest-mediators and the government’s Blood Feuds Reconciliation Committee, the current estimate (cited in a recent London Sunday Telegraph story) is that 11,000 males, some as young as 12, are hiding in their homes or in towers because of blood-feud involvements. In the words of relatives of a man from the Northern village of Prosek shot by a neighbor who is now jailed: “we cannot accept this humiliation. The government put him in prison, not us. We want blood for blood, we want revenge according to our traditions.”

So the cycles have come full circle and back again. Byron’s verses apply equally to the Albania of Pyrrhus, Lek Dukagjini, Skanderbeg, Zog, Hoxha, Berisha, and the new president Rexhap Mejdani:

Albania’s chief, whose dread command

Is lawless law, for with a bloody hand . . .

The wild Albanian kirfled to his knee.

With shawl-girt head and ornamented gun.

Leave a Reply