“What do you expect of a spiritualist? His mind’s attuned to the ghouls of the air all day long. How can he be expected to consider the moral obligations of the flesh? The man’s a dualist. No sacramental sense.” So speaks one of the characters in a Muriel Spark novel. G.K. Chesterton thinks along similar lines. He also regards the loss of a sacramental sense as the defining characteristic of the modern world. Like Muriel Spark, he regards the retreat to private worlds of the spirit as a religious problem, since those who isolate themselves in this way cut themselves off from the voice of God who speaks to man through material things. But Chesterton makes a further point. He also believes that a people who sever themselves from the materialities of everyday life often invent parodies of the material realities with which they have lost touch. In his view, in such a post-Christian spiritualist society, the old Christian truths never entirely disappear: they are merely transmuted into new and strangely abstract shapes. “All the tools of Professor Lucifer,” he writes, “were the ancient tools gone mad, grown into unrecognizable shapes, forgetful of their origins, forgetful of their names.” In Orthodoxy (1908), commenting on the loss of solidly material communities in which real virtues are embodied, he describes the modern world, not as something evil, but as something crazed and disconnected from reality, a realm in which disembodied Christian virtues have gone mad because they have become isolated from each other.

Contemporary life provides many examples of the sacramental parodies to which Chesterton refers. It would, for example, be easy to draw up a more or less random list of ceremonies of contemporary secular life that mimic, in a weird way, the beliefs of the Christian faith. This strange list is full of ironies. In a world in which the fear of damnation is no longer a matter of general concern, the therapist becomes the modern confessor, providing psychologically troubled souls with a secular substitute for sacramental forgiveness of sins that, in psychological theory, do not in fact exist. In an age which rejects religious authority, the ever-changing pronouncements of modern scientists are accepted with religious trust. In nations which have lost a sense of spiritual peril, dangers to physical health are regarded with the same horror with which religious people used to regard mortal sin, and increasingly extreme measures are taken to protect citizens from such moral threats as secondhand smoke or unhealthy food. Recently, for example, one of the most thoroughly de-Christianized societies in the Western world, came close to abandoning its age-old tradition of raising beef for food because of a mass hysteria whipped up by television and newspaper reports about a danger to physical health that was statistically so remote that even the scientific authorities whose contradictory studies were the basis for the panic became frightened by the irrationality which their reports had unleashed. In a popular and largely urban pornographic culture, moral environments as polluting as open sewers are regarded with complete indifference; yet, at the same time, city-dwellers express growing concern about possible damage to the forests and wilderness regions with which few of them will ever have any direct contact—”the swaying tall pines among the litter of cones on the forest floor,” real places which remain for them what they are for Muriel Spark’s self-destroying modern heroine in The Driver’s Seat (1970)—a mental construct, a country of the mind. So, too, with the traditional belief in a “communion of saints,” as affirmed in the age-old Christian creeds. This faith in the existence of a real but mysterious community of the living and the dead is replaced by a belief in a mock community of the Internet—an abstract and shifting fellowship of wraithlike beings who are incapable of making any permanent commitments, because, to borrow Muriel Spark’s phrase, no meetings between them can ever materialize. There are even parodies of traditional religious festivals. In international athletic competitions, nations that no longer worship God organize secular celebrations which take on the trappings of religious worship, and the celebration of youth and of physical fitness becomes a sinister analogue to the Christian hope in a world to come where there will be no more aging or death and where those who can no longer die will remain perpetually young.

If nothing else, the reading of authors such as Muriel Spark and G.K. Chesterton helps one to understand such contradictions. No one familiar with their writing would imagine that the difference between religion and irreligion is a simple contrast between those who believe in the unseen world of the spirit and those who believe in the world of empirical realities, as though the great modern opposites were the religious spiritualist and the irreligious materialist. For these two authors, the opposite is closer to the truth: Christians are the true materialists, and nonbelievers are the spiritualists.

Chesterton’s critique of spiritualism had its origin in a crisis which occurred in his own life. A personal problem provided him with an insight into the characteristic problem of his age. As a student at the Slade School of Art in the mid-1890’s, the young Chesterton went through a time of complete moral and mental isolation. For a brief while, he entertained the possibility that nothing existed outside his own lonely mind. What such an experience of living in a solipsistic universe means in practice is described in books such as his Autobiography (1936), and The Poet and the Lunatics (1929), and, above all, in his strange 1908 novel The Man Who Was Thursday—a symbolic narrative in the Kafka mode: it is subtitled “A Nightmare,” but it is irradiated with a joy unlike anything found in Kafka’s own writing. When Kafka himself read the book, he commented memorably: “The author is so happy, that one might almost believe that he had found God.” It could be said that Chesterton devoted the rest of his life to examining the religious and philosophical, and even the social and economic, implications of his escape from solipsism. I lis novels, his fantastically improbable short stories, his verse, and the unending stream of parables, of visionary utterances, and of moral maxims which form his vast journalistic output are all part of a single effort to stimulate the sleeping imaginations of his readers, so that they too would be capable of escaping from their own private worlds and make contact with the world of other people and of other things.

It is important to understand that for Chesterton the recovery of a material world was also a key religious experience. The fundamental Christian doctrine, after all, is the Incarnation. In Chesterton’s view, this central religious belief alters the relationship between the world of spirit and the world of matter. After the coming of Christ, the spiritual and the material can no longer be separated. “A Christian,” he explains in his 1933 book on St. Thomas Aquinas, “means a man who believes that deity or sanctity has attached to matter and entered the world of the senses.” And again, he writes, “the trend of good is always towards Incarnation.” Moreover, as he explains in one of his early Illustrated London News articles (September 22, 1906), material things provide the only sure way to get in touch with the world of the spirit: “Whenever men really believe they can get to the spiritual, they always employ the material. When the purpose is good, it is bread and wine; when the purpose is evil, it is eye of newt and toe of frog.” For that reason, physicality acquires a moral and a religious significance, and the distinction between the sacred and the profane is no longer a distinction between the spiritual and the material.

In a chapter in his book on St. Thomas which he entitled “A Meditation on the Manichees,” he comments on what he calls “the tremendous truth” that supports all Christian theology: “After the Incarnation had become the idea that is central in our civilisation, it was inevitable that there should be a return to materialism, in the sense of the serious value of matter and the making of the body. When once Christ had risen, it was inevitable that Aristotle should rise again.” A respect for material things is, therefore, a sign of sound Christian faith. “You become more orthodox,” Chesterton explains, “when you become more rational or natural.” For Chesterton, the existence of the most ordinary and transitory material things is given a new and religious meaning by the life, death, and resurrection of the Incarnate Word. Comparing the teaching of St. Thomas to the writing of the modern Irish poet “A.E.,” Chesterton asserts that the saint has the right to borrow the poet’s words: “I begin by the grass to be bound again to the Lord.” In his view, the mark of all genuine religion is that it is grounded in the material. When material things deceive us, they do so, he explains, “by being more real than they seem.” He goes on to say: “As ends in themselves they always deceive us; but as things tending to a greater end, they are even more real than we think them. If they seem to have a relative unreality (so to speak) it is because they are potential and not actual; they are unfulfilled, like packets of seeds or boxes of fireworks. They have it in them to be more real than they are.” In his Autobiography, one of the final books that he wrote, he asserts that his own philosophy might be expressed by reversing the title of an early Yeats play, Where There is Nothing There is God. “The truth presented itself to me,” he writes, “rather in the form that where there is anything there is God.”

This celebration of the religious value of materiality gives a special power to Chesterton’s critique of modernity. For him the modern error is to have lost touch with the material world. Political life and vast economic systems and huge shapeless ideologies all share one essential fault: they are unreal; they substitute a world of shadows for a world of things. In small communities, people are in direct contact with primary things; in vast bureaucratic systems, people are condemned to a life of servile complexity, to what he calls a “spirit of illusion, of indirect rather than direct things.”

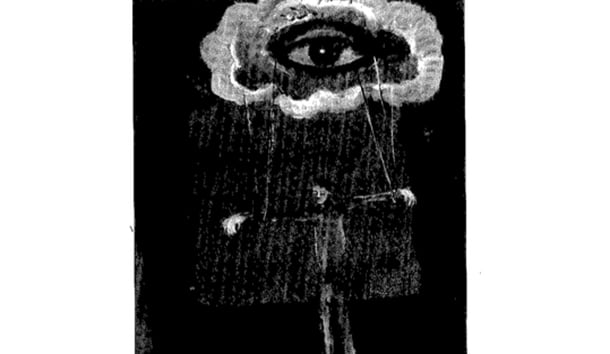

In such a solipsistic world, it is impossible to hear the voice of God as He speaks to man through other people and through the direct experience of real things. The very wealth of the modern world cuts people off further from reality. It is understandable that in all his fiction and journalism, Chesterton defines evil as “the destruction of the material, simple things,” and Christian faith as “a religion of little things.” Not surprisingly, he describes the complexities of modern life as a kind of madness, a “final divorce” from such realities as what he calls “liberty in small nations and poor families” and “the rights of man as including the rights of property; especially the property of the poor.” In a sermon he gave to a congregation in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1905, he commented on the dangers of fragmentation in modern life, the way in which liberal individualism resulted in a condition of solipsism in which each person constructs a private shadow world out of his own isolated experiences and inner needs. Citing a passage from the Book of Proverbs (29:18)—”where there is no vision, the people perish”—he goes on to assert the need for a faith which will give unity to an otherwise meaningless existence: “The people who follow wicked, fallacious visions, wrong visions, end in great disaster and terrible punishments, but the people who do not follow any vision at all do not exist or cannot exist for long.”

The corollary of Chesterton’s celebration of a philosophy which respects the religious value of material things is his distrust of philosophies and religious and political systems which exalt the inner life at the expense of the outer life. As he points out, the work of heaven is entirely material, and the work of hell is entirely spiritual, hi his view, an attachment to a family, to a small community, and to a particular place is the basis of moral and political health. In Manalive (1912), his hero insists, “God bade me love one spot and serve it, and do all things however wild in praise of it, so that this one spot might be a witness against all the infinities and sophistries, that Paradise is somewhere and not anywhere, is something and not anything.” For him, even extreme evil such as devil-worship is recognized by its lack of material definition: those who worship the evil one, he explains, “always insist upon the shapelessness, the wordlessness, the unutterable character of the abomination.”

But the writer who develops the Chestertonian critique of spiritualism furthest is his coreligionist Muriel Spark. Only after her conversion to Chesterton’s sacramental religious faith did Mrs. Spark begin to write the novels which earned her the reputation as one of the most urbane critics of modern life. At home in numerous small worlds, her novels record with witty and realistic precision the particular details of ordinary life in such small communities as that of Miss Jean Brodie’s Edinburgh in the 1930’s, of bored and restless expatriates in rural South Africa in the 1940’s, of the sharply observed intellectual coteries of World War and post-World War London, as well as of the divided communities of modern Israel, or of contemporary Manhattan and of the film star world of modern Rome. Yet in spite of the wealth of realistic documentation, her characters’ lives remain fantastically artificial and unreal. Only in the language with which they describe the unreal financial system to which they cling for security do they project an image of the natural world from which their lives are cut off: “They spoke of the mood of the stock-market, the health of the economy, as if they were living creatures with moods and blood. And thus they personalized and demonized the abstractions of their lives, believing them to be fundamentally real, indeed changeless” (The Takeover, 1976).

Like Chesterton, Muriel Spark writes increasingly improbable fantasies in order to draw attention to the growing unreality of modern life. In one way or another, all the unhappy people in her novels are in flight from the material universe: each of them lives in a totally private world. In a typical conversation in Memento Mori (1959), someone wonders whether or not other people are in fact real. In Muriel Spark’s version of the modern world, the question is not an easy one to answer. In this instance, however, it happens that the characters in conversation are near a graveyard, and that one of them is a Christian believer and herself a novelist; pointing to the graveyard “as a kind of evidence” of the reality of other people, she asks: “Why bother to bury people, if they don’t exist?” In The Hothouse by the East River (1973) the solipsistic nightmare has become the only reality. Paul and Elsa, the main characters, turn out to be people who are dead, but who refuse to accept the fact of their own deaths; and the people whom they meet in the nightmare city of Manhattan are fantasies whom they themselves have invented. “How long, cries Paul in his heart, will these people, this city, haunt me?” The satiric point concerns the unreality of an urban life so cut off from natural things that it is impossible to distinguish fantasy from reality, and the dead from the living: “You would think they were alive,” someone says, “one can’t tell the difference.”

Both Chesterton and Muriel Spark suggest the same solution to the solipsistic nightmare of modernity. Since the problem originates in the separation of the sacred from the profane, both authors advocate that the material and the spiritual be brought together into a single whole. In The Mandelhaum Gate (1965), a novel devoted exclusively to an exploration of the consequences of a fragmented existence, Barbara Vaughan, the central character, expresses a belief in such a unified existence: “Either the whole of life is unified under God,” she says, “or everything falls apart.” In The Bachelors (1960), one of the characters asks, “Afraid? What is there to be afraid of?” The answer to this disturbing question is that people must learn to fear the stubborn realities which will continue to exist even when their existence is denied—such realities, for example, as the “four last things” referred to in the uncompromisingly direct question and answer of the Penny Catechism which provides a title for Memento Mori. To the question, “What are the four last things to be ever remembered?” the Catechism answers simply: “The four last things to be ever remembered are Death, Judgment, Hell and Heaven.” In The Bachelors, the girl who may soon be murdered by her spiritualist boyfriend is reluctant to acknowledge the danger in which she lives: “Yes,” said Alice’s voice in the dark, “I’m afraid of the things I don’t know. I don’t want to know.”

What both Chesterton and Spark recommend as a solution to the problem of solipsistic isolation is the recovery of what they call a sacramental sense. In principle, both authors acknowledge that the dualistic separation of the material and the spiritual has already been overcome by the coming of Christ. But their writings demonstrate the difficulty with which the lost unity can be recovered in human lives which are supposed to be, but which so seldom are, sacramental reenactments of the one Gospel story. Chesterton, who is a philosopher as well as an imaginative artist, has ideas about ways in which small communities of faith might be constructed, places that would provide a setting in which the perennial human drama is more likely to come to a happy ending. Muriel Spark is content to observe the contemporary disorder with a satirist’s eye, and to assert through her fiction a conviction about the need to recover “a balanced regard for matter and spirit,” without ever quite explaining ways in which this might be done. Chesterton once wrote that, in the end, the only thing important is the destiny of the human soul. In every one of the stories in which he describes characters struggling to escape from solipsism, he presents people who do what he himself once did, by turning from their private obsessions to the sacrament of marriage. Muriel Spark would approve of that practical solution to the problem of spiritualism. As one of her own unhappy bachelors explains, “I’m afraid we are heretics, or possessed by devils. . . . It shows a dualistic attitude, not to marry, if you aren’t going to be a priest or a religious. You’ve got to affirm the oneness of reality in some form or another.” Yet when it comes to the essential question of the salvation of the human soul, she would also understand the profoundly sacramental implications of another Chesterton saying—that forgiveness of sins is essential to the communion of saints and the resurrection of the body to life everlasting.

But in a world in which the sacramental sense remains atrophied, no one should be surprised at an odd and growing list of bizarre spiritualist substitutes for the sacraments which the non-sacramental modern world refuses to accept. If Chesterton and Muriel Spark are right, these sacraments alone can restore unity to divided people and to divided societies. In the meantime, there is need for poets and novelists whose improbable fictions will awaken the imaginations of their readers and enable them to recognize the fantastic character of the unreal world in which they are immersed.

Leave a Reply