In a recent interview in New York magazine, writer Jamie Hood responded to question about justice. Hood, the transgender author of a new book Trauma Plot: A Life, claims to have been raped three times in the span of two years between 2012 and 2013. One of the alleged rapes, Hood says, was at the hands of five men. Asked by reporter Grace Byron what justice would look like after such trauma, Hood answers with this:

I don’t know what it looks like. There was no point in time where I was like, I’m going to report. I went into a police precinct once, and it was after the last time I was raped, and it was because [the assailant] had robbed me and taken everything. My Social Security card was in there, my license, every sort of important document was in my wallet. Of course, you look back on that and think, What if I had just left my wallet at home and carried cash on me that night? But I went in, not even to report the rapes, but to see if I could find my wallet and I was in there and the police laughed at me. You know, they laughed. It was not that it was even surprising to me. But it was paralyzing.

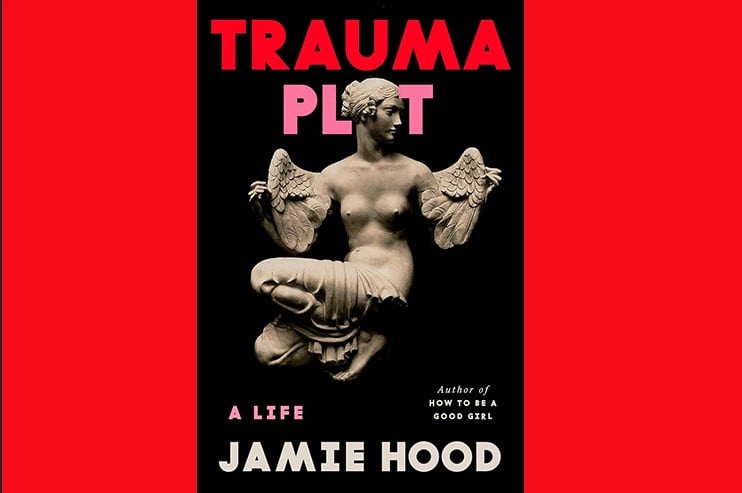

In Trauma Plot, Hood, a “transgender woman,” claims that rape is a regular part of our patriarchal culture, like the air we breathe. It’s also said to be “political” and thriving in the age of Trump. It is also obviously devastating. “Rape severed me from time,” Hood writes, “of which I lost much, in terms of memory and self-presence, yes, but also in the sense of just living—I don’t know if I was doing that until recently. In an early poem I wrote for the book, I described myself as a ‘persistence of biology.’ The years passed through me. Was this like life? The way trauma annihilates time seems to me one reason we consider it unspeakable.’”

Reading Hood’s interview and then reading Trauma Plot, I was left with two impressions. The first is that Jamie Hood, as in the example above, has a penchant for interacting with authority figures who are unfailingly cruel, uncaring, and indifferent to the suffering associated with rape. Secondly, Jamie Hood has the consistent misfortune of getting sexually assaulted in circumstances that make it nearly impossible to catch the perpetrator—even in an age of ubiquitous video cameras and cell phones. These facts alone make it exceedingly difficult to believe the claims made in Trauma Plot.

Take the incident of the “Man in the Gray Room” as Hood describes it in the book. Hood details an alleged rape and sodomy in Boston with great attention to the graphic physical details.After the alleged rape Hood asks the man for a ride home, and the man obliged. No detail is given as to where the attack took place. It’s just “the Gray Room” somewhere in Boston.

Hood describes another rape by a man Hood calls the Diplomat. Hood and a friend called Serena are partying with two men somewhere in Boston. Hood and the Diplomat begin some sexual activity, but then Hood decides against it. She asks Serena for help getting home:

I told Serena how I needed to get out of there. She was fixed on the other man like a barnacle; she didn’t hear me at all. Again I asked, did she want to come with? She waved me off. Did she have any cash, I said I needed to find a cab and had nothing left, my card was overdrawn, but she went on kissing the other man. They were someplace else. Maybe the Diplomat was in the bathroom then, or making drinks in the kitchen. He’d gotten insistent in a way I found unnerving. I thought to slip away unnoticed, as if anything about me in that moment was discreet. My body was overloose; the room hot and full of smoke; everything spun.

The rape Hood then describes is said to have taken place in a room where Serena cannot see it. No charges are filed.

That’s awful but certainly there must be witnesses or video footage of Hood’s assault at the hands of five men. Nope. Hood simply reports walking down a street in Boston one night when a car with five men inside approaches. The driver is described: “Beneath the glow of the streetlamp she saw his teeth, yellow and sort of crooked, and his skin, milk pale, jagged with old acne. He smiled then, a smile that stalled in the lower half of his face. How obvious the look was, how fabular: his grotesquerie, that wolf’s grin. C’mere. This wasn’t a question. In the car’s dark rear, two cigarettes.”

In the age of street cameras and ubiquitous cell phones, somebody had to have seen something, right? At least the street can be named? Afraid not, as Hood adopts the third person to describe the scene: “Motionless, Jamie scanned the street for other people—for witnesses. No one, and no cars coming, which was unusual for the hour but not impossible. She saw then that in her absentmindedness she’d wandered off the main road. She was on a side street she took sometimes, a bit wayward, but one she liked walking down, because of an amiable black lab who roamed a fenced yard along it.” Can hood at least identify that black lab?

The closest we get in Trauma Plot to a specific time and location, and an actual witness, is in the description of an incident that takes place at the Barnes & Noble store in Virginia Beach. Hood, then 13, was in the store when

a man corners me among the shelves. He’s old and bald and has a visible erection tenting his khakis. He starts rubbing himself on me. I go still. I’m under the bed again. He’s smiling and whispering something to my body about where his car is parked in the lot, and couldn’t I just follow him there? My body doesn’t reply. It doesn’t scream. When a store employee turns into the aisle he flees. The woman’s face is red, red as the dog’s strawberry nose, and she storms toward my body, snatching a CosmoGirl from its clenched hands. BOY TROUBLE. GET YOUR CRUSH TO WORSHIP YOU. THE BEST JEANS FOR YOUR BUTT. She says I should be ashamed of myself, she says how disgusting I am—there are children here, she seethes. I am thirteen.

We can’t say for sure when this assault took place. We are simply expected to believe that an employee of Barnes & Noble turned a corner to find a 13 year-old being subjected to a sexual assault and deciding then, to upbraid the teen. Can we find this employee? What did she look like? What time of day was it?

In the New York interview Hood makes a claim about a visit to a police precinct to retrieve a wallet after a rape. Where was the precinct?

Hood also has an amazing run of bad luck when it comes to other authority figures and colleagues. When getting tested for AIDS, Hood tells a doctor about being raped:

The tears poured out of me then, and I found myself apologizing, I said I didn’t know why I was telling him this but maybe it was useful information. I said I tore easily during rough sex, and there was blood after he’d finished with me, which seemed a bad sign. I said the word “seroconversion,” sobbing. I couldn’t believe he was the first person I’d told about the rape. The doctor’s sternness slipped a moment; his face went all dim and flat. I liked that. I liked seeing him realize how small and cruel he was. He began to stammer, to tell me, oh no, it’s just we’re not equipped for this, we’re not the sort of clinic that handles people like you, we don’t conduct rape kits, and was I sure, because really, he didn’t have the expertise.

There’s also no sympathy from the colleagues at the “dive bar” where Hood worked before getting fired. Hood claims the gang rape was orchestrated by a local drug dealer, and that no one at the bar cared when this sinister character reappeared in the neighborhood. The owner of the bar calls Hood a liar and tells customers to dismiss the wild stories. The other workers and friends don’t care:

And this sense of having mattered, of having been someone for whom life has matter, is bound up there too, in no small part (in my case) because this world doesn’t believe trans people have a right to exist at all. A few weeks ago I told you about my ousting from that awful bar, and how simple it must have been for the owners to paint me as crazy and a liar, to weaponize discursive panics about hysterical “victims” and degenerate trans freaks. So then I found, later, that some of my closest friends kept hanging out there afterward, kept chumming around with those men. Which was a stark reminder of my place—that these people I’d spent nearly a decade with were so willing to discard and discredit me, and for what? Some dingy, broke-down, rapey little dive. My friendship was totally inconsequential when weighed against a buy-one-get-one IPA.

To anyone who has worked in a bar, this just comes off as completely bizarre, even foreign. Co-workers in places like that form tight bonds and stick up for one another when one of the team is attacked. Yet Hood is just dismissed and ignored? Flatly called a liar by management? That seems like a red flag.

Let’s summarize. Transgender author Jamie Hood claims to have been raped three times by seven people in two major American cities. Hood is met with laughter by police, dismissed by colleagues at work, ignored by a doctor, and scolded while being assaulted—when only 13 years old—by a clerk at a well-known bookstore. There is no video footage or photographic evidence of any of this. Nevertheless, Trauma Plot has received strong reviews—and while interviewing Hood, NPR host Brittany Luse started crying. “The stories don’t have to be super conventional,” Hood told a crying Luse.

Conventional or not, it’s all just part of the ongoing oppression of the patriarchy I suppose.

Hood decided to write Trauma Plot after a tape came out in 2016 of Donald Trump using crude language to talk about women. There was also the infamous Brett Kavanaugh saga, when the then Supreme Court justice nominee was accused of sexual misconduct in high school by Christine Blasey Ford. Of that episode, Hood writes:

Kavanaugh’s ascension to the Supreme Court seemed to me the first meaningful death knell of #MeToo. Not because Ford’s legitimacy as a witness of her own life was well challenged—it was obvious she was credible; even Trump yielded the point—but because it served to show no one much cared if a woman was violated or not, particularly if the perp was a man turning any special wheel of power. In her memoir, Ford writes that it “didn’t feel like I hadn’t been heard. It felt like I had been believed, [and] the response was a proverbial shrug.”

A shrug? America turned itself upside down trying to verify Ford’s claims. There was a congressional hearing and an FBI report. The media went crazy. (Full disclosure: I was a part of that circus, and you can read my account of that fiasco in my book, The Devil’s Triangle.)

At the end of Trauma Plot, Hood offers this: “If my rapists are made identifiable by this book, I don’t care. I no longer need vengeance, and I hope they rot.”

Well, I do care. Where was the police precinct where Hood went to retrieve a wallet—the place where officers laughed at Hood? Who was the Diplomat? What doctor dismissed Hood’s rape story, and where was the clinic? Who is the owner of the dive bar where Hood worked—the owner who called Hood a liar? What did the clerk at Barnes & Noble look like?

In Trauma Plot, Hood laments the end of #MeToo. Yet what Hood seems to miss is that it was precisely books and stories like this that caused the movement to collapse.

Leave a Reply to Sam Cox Cancel Reply