The government continues its reckless deficit spending and yet inflation is back under control. What is going on?

In the 12 months ending in November, the publicly held national debt climbed to $26.7 trillion from $24.5 trillion. Conventional wisdom holds that deficit spending causes inflation. But something of a black swan event has emerged to demolish conventional inflation-fighting doctrine.

Naturally, the Biden administration has made political hay out of this trend, and the president has bragged that he’s reducing inflation. Of course, this does not mean that prices have fallen to pre-pandemic levels—the prices of food, fuel, and everything else remains much higher than they were before Biden became president.

Nearly 18 months ago, I wrote that the Federal Reserve was not raising interest rates enough to check inflation. The reason was that historically interest rates need to be at least 1.5 times the existing inflation rate to prevent holding cash from being a money-losing proposition. Everyone can feel the value drain on money as grocery and gas bills increase faster than wages. It turns out I was wrong—the Fed was actually able to slow the inflation rate. So how are we getting the benefit of declining inflation while the economy continues to grow? Have we magically escaped the “doom loop” predicted in 2022?

Unfortunately, no. For average Americans, the long-term result of what’s happening will eventually mean more “taxflation,” more government borrowing, higher borrowing costs for the average consumer, and an acceleration of the inevitable debt apocalypse.

To understand what’s happening, we must first explode two things “we know” about the Biden economy. First, domestic energy production has reached record levels under Biden. The president may have fooled his base. But Biden’s America pumps more oil than at any other time in our history, even under Trump. As oil costs influence all other costs, the rising production helps bail out the Biden administration from its inflation mess. Second, despite massive government spending, the M2 money supply actually shrunk.

What differentiates the Biden administration’s effort at inflation-fighting from others in previous administrations is that the Fed can use its gargantuan stockpile of bonds to suck money out of the economy as the IOUs come due and the Treasury pays them off. Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed has used bond purchases to stimulate the economy. From September of 2008 through approximately the end of November 2023, the Fed responded to the collapse in the mortgage-backed security market with dubious purchases of the troubled mortgage-backed-securities in addition to treasuries. These purchases continued for more than a decade as the housing market became addicted to the Fed’s subsidy of the mortgage-backed bonds. In total, the Fed more than doubled its holdings from less than $1 trillion in bonds pre-2008 crisis to around $2 trillion just a few weeks later.

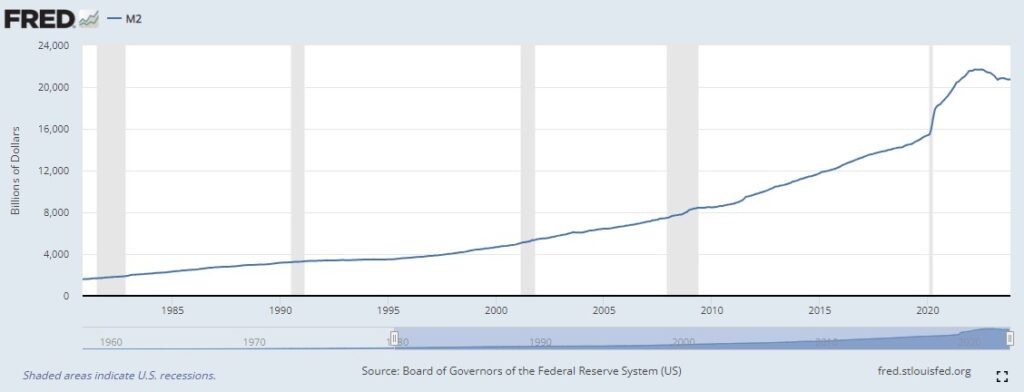

Throughout the anemic recovery under the Obama administration, the Fed continued purchasing more and more assets, calling the program “quantitative easing,” to stimulate the economy. The project stole purchasing power of the dollar to accommodate reckless federal spending. Then when the pandemic lockdowns froze the economy, the Fed printed enough money to increase its stockpile of bonds from $4.15 trillion (in January 2020) to just under $9 trillion in the spring of 2022. Meanwhile, the M2 money supply ballooned from $15.4 trillion pre-pandemic to almost $22 trillion in roughly the same period. While many factors influence the money supply, we can trace much of the expansion right back to the Fed’s bond-buying spree.

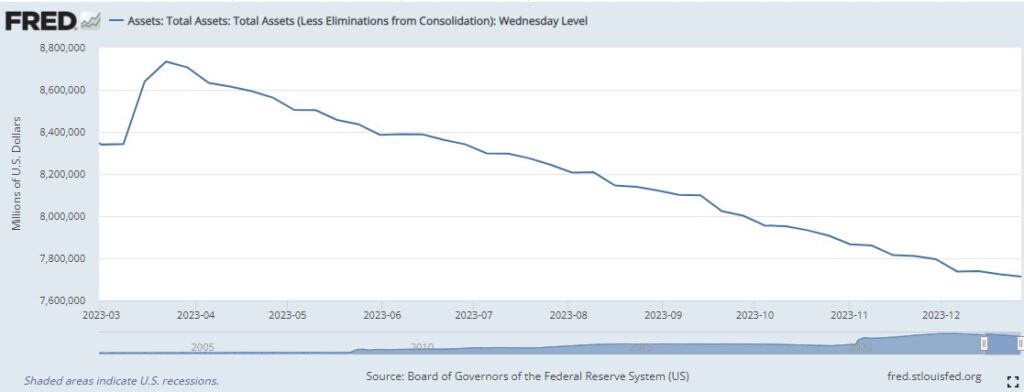

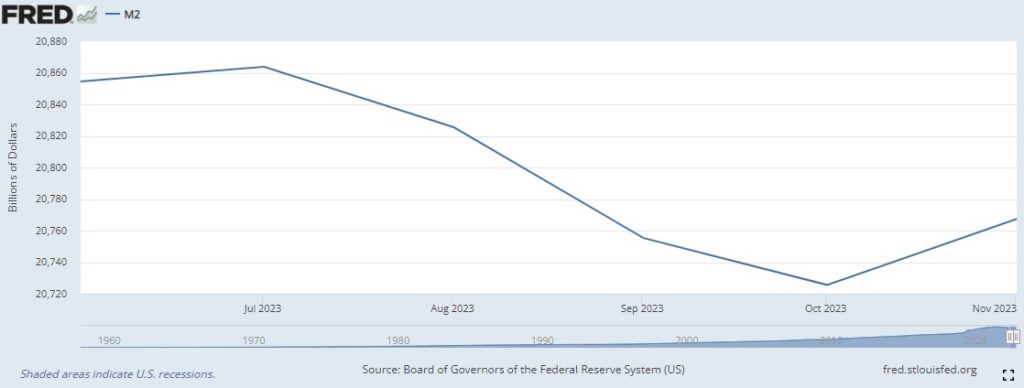

But then inflation heated up to crisis levels, so the Fed announced it would no longer buy these bonds. When the Fed prints money to buy trillions in bonds, it makes borrowing for the Treasury really cheap. In July of 2020, the 10-year treasury paid 0.53 percent which is well below the rate of inflation. In other words, the rates were effectively negative because buyers seeking the bonds had to compete with the Fed. The Fed uses printed money to bid on the bonds. This, in turn, drove the prices up (think of the “price” of a bond as the inverse of the interest rate). Since the Fed stopped buying treasuries, approximately $1 trillion in Fed-owned bonds have disappeared as they matured. The Fed just kept the money the Treasury paid when bonds reached maturity. Consider these two charts. The first shows a nearly perfect straight-line drop in the total bonds held by the Fed since the spring of 2023. The second chart shows that during roughly the same period, the M2 money supply actually shrank by almost $100 billion.

Now compare that chart to the M2 money supply:

The Fed pulled roughly $1 trillion out of circulation by allowing bonds to expire. That was enough to overwhelm the forces that normally expand the money supply, with few exceptions. Consider this chart which shows a long-term history of the money supply.

Add to that Biden’s mass immigration and the surge in domestic oil production and you get a very effective anti-inflation cocktail, which seems to have resulted in a soft-landing without wrecking the economy the way the Fed did in the early 1980s.

The process has already resulted in an explosion in the interest rate the treasury has to pay on new debt. Yield on a 10-year treasury soared to nearly 5 percent in October before falling back to around 4 percent today. That has already caused the Treasury’s interest obligations to nearly double since the start of the pandemic. And it’s also causing other market rates to rise, particularly mortgage rates which roughly tracked the yield on treasury bills by shooting up to a peak in October before retreating to the roughly 6.61 percent we have today. But the higher treasury yield and mortgage rates are tolerable consequences of a policy that seems to have stopped inflation without causing recession.

To the wonks in Washington, this looks like a get-out-of-jail-free card. The Fed can underwrite nearly unlimited spending until inflation becomes politically painful. From now on, the federal government will never again use interest rates alone to fight inflation. If the Fed can stop inflation without raising interest rates to recession-inducing levels, then the spenders in Washington imagine they will have a blank check.

But there’s no such thing as free money. As Milton Friedman used to say, somebody has to pay for every lunch. So how will we pay for Biden’s free lunch?

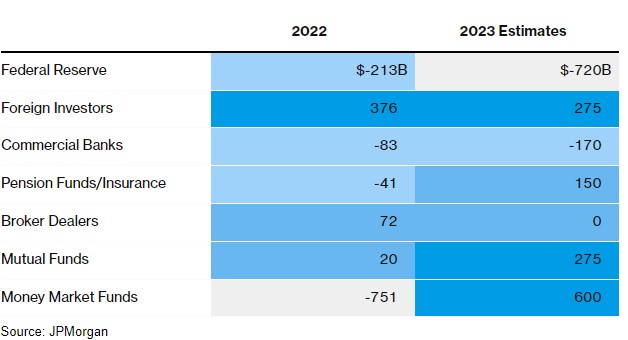

First, we will likely see a return to instability in the mortgage-backed securities market. 2023 was the first year since 2008 that the Fed didn’t backstop the market by buying large quantities of MBSs. Second, as noted by Bloomberg, the two biggest traditional treasury buyers, the Fed and China, have stopped buying. The replacement buyers are buying for profit and will no longer tolerate rates that are effectively negative. That will raise borrowing costs for everyone as the treasury yield is always the starting point for market rate setting.

The federal government must now beg for money from mutual funds, money markets, and pension funds. The shift in buying is dramatic. Mutual funds increased bond purchases at more than ten times their normal rate. Money market funds shifted from a net seller of $751 billion in bonds to a net buyer of $600 billion. That’s a $1.3 trillion swing. This is not stable or sustainable.

But for now, the policy seems to be working in the short run. Biden will get his inflation-reduction headlines without an economic crisis just in time for the next election, which will likely happen before the house of cards tumbles down. But that’s a feature, not a bug, to left-leaning economists who see every crisis as an opportunity. Upon Biden’s re-election, he may have yet another “emergency” that can be used to expand government power and leftist causes. Modern monetary theory only works when the system remains on the verge of collapse at all times. Otherwise, nobody would hoard useless paper cash.

Leave a Reply