What, no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq? This development has resulted in the sort of newsroom hand-wringing that one usually finds only when a reporter for the nation’s most prestigious newspaper is caught fabricating quotations in scores of news stories.

Where is the liberal media when we need it? There is no question that the journalism profession is populated, top to bottom, with people who share a liberal vision of the world. This is a source of constant frustration to conservatives and libertarians, since news editors and reporters always see the good in government agencies and refuse to give serious attention to information that, say, casts aspersions on the one constitutional right left in this nation—the right to an abortion.

Presumably, modern liberals should not like wars, especially ones waged by Republican presidents. Yet, in the nation’s newspapers, there was very little skepticism toward the Bush administration’s bogus claims about the threat Saddam Hussein posed to the world.

Editor & Publisher, an industry publication for journalists, featured an opinion piece on its website on June 12, asking whether the press was asleep at the wheel before the war started with regard to WMD’s. As columnist Joe Strupp wrote:

Although newspapers before the war did report the disagreement between administration officials and U.N. weapons inspectors, few major papers took the issue on full-throttle with demands for answers—or dissected the sketchiness of the administration’s evidence of vast stockpiles of WMDs.

What explains the lack of zeal for covering serious stories about this war—beyond, perhaps, the media’s typical willingness to trust official government sources for their information? The media does not have a leftist bias, in the sense that it is filled with crusading far-left reporters of the sort who write for the Nation. Sometimes, that would be better than what we now have, since the lefties were among the few writers gunning for the war.

Mostly, reporters and editorial writers have an establishment-liberal bias. They see the world in much the same way that a standard-issue Democratic member of Congress or president might see the world. Their only real opposition comes from the establishment right, as seen in the chest-pounding pro-war propaganda from the alternatives to the liberal media. That does not leave much of a choice for those of us whose views fall outside that narrow band of center-left to center-right. Who are you going to believe: Dan Rather or Bill Kristol?

Granted, some newspapers have provided good coverage of the downside of the war, at least in its aftermath. Mainstream newspapers, especially such prestige papers as the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post, have reported on the increasing strength of Islamic fundamentalist movements, attacks on Christian shop owners in Iraq by Muslims, and many other negative side effects of the war.

I am pleased to see such coverage, however late; I am still bothered by the climate that surrounded journalism in the early part of the war, however. For a while, it seemed as if there would be long-term negative consequences for the freedom and openness of the press, as advocates of war, egged on by the neoconservative media (Fox News, National Review, the Weekly Standard), tried to paint all opponents of the war as sympathizers of dictatorship or nutty leftists.

That fear has passed, but it is worth thinking back to the early days of the war. There was a broad sense throughout the country that opposition to the war bordered on treason. Media liberals had mixed feelings but were unwilling to ask the tough questions. Remember how the Democratic presidential candidates acted? They did not really support the war, yet they refused to voice anything more than the most tepid objections.

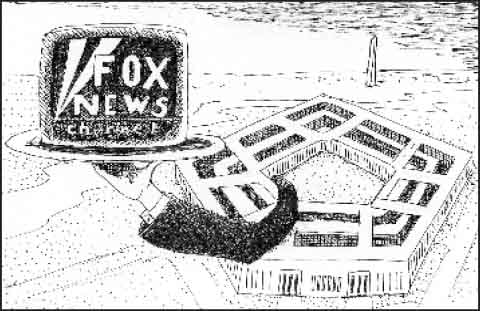

The neoconservatives, however, were on the offensive. As a longtime hater of the dominant TV networks, I have applauded the emergence of Fox News as a reasonable alternative. While a great deal of its programming is lightweight, I appreciated a lineup that included a steady stream of nonliberal voices. Yet I came to loathe Fox during the war, as it morphed into a propaganda arm of the Pentagon.

Fox led the “Shut up, you traitor” chest-pounding that influenced the lack of broader coverage of the war. In a column I wrote for the Orange County Register on March 30, entitled “Confessions of a Bad American,” I raised questions about the apparent lack of weapons of mass destruction and about the administration’s exaggerated case for an offensive war against a distant country.

My main target was Bill O’Reilly, the Fox News talking head who was leading the pro-war cheering section:

Criticism of the war, while bombs are flying and coalition troops are under fire, makes me a “bad” American, according to a certain blow-hard commentator whose idea of tough journalism is badgering guests with comments such as, “Come on, Mr. So and So, you don’t really believe blah, blah, blah.”

Although he apologized for labeling as “anti-American” anti-war protesters who demonstrate during the war, Fox News commentator Bill O’Reilly argued on March 3 that “I will call those who publicly criticize our country in a time of military crisis, which this is, bad Americans . . . [I]t is our duty as loyal Americans to shut up once the fighting begins, unless—unless facts prove the operation wrong, as was the case in Vietnam.”

O’Reilly’s words typified what was going on at the time: an effort to get those who opposed the war, on the right or the left, to shut up and back the President rather than engage in honest debate.

As an editorialist, I am not exposed to the pressures that occur in the newsrooms. My newspaper, the Orange County Register, maintains a strict wall of separation between the editorial page and the rest of the newspaper. The company’s libertarian editorial philosophy is in stark contrast to the liberalism typical in our newsroom, as in most other newsrooms in the country.

We had free rein for our antiwar views. So I wrote what I wrote about the war and got nothing but support from my bosses. I cannot complain. Nonetheless, I was subject to pressures unlike any I have felt before.

Our editorial-page readers are a conservative bunch, and they occasionally get annoyed with the libertarian leanings of some of our positions. To much of the public, issues are liberal or conservative, period. Chronicles readers probably share the same frustration, since paleoconservatives, like libertarians and paleolibertarians, tend to break the mold.

Understandably, these regular readers were mad at us. They did not like our attacks on the President and genuinely believed that criticism of a war while it is going on is borderline unpatriotic. Still, most of our regular readers are surprisingly polite and honorable in their disagreements. I received heated calls and e-mails, but that is part of the fun of being in the editorial-writing business. It was not much different from what I had experienced on other particularly contentious issues.

Then one day, while traveling out of state, I called to check my voice mail, and it was full of bitter, angry, nasty, ignorant messages of the “Why don’t you move to Iraq, you commie” sort. These were angry people. When I got back to the office, my e-mail was filled with the same sort of vitriol. People were calling my editor, and there was an obvious attempt to clamp down on the Register’s editorial voice.

What had happened?

On his nationally syndicated radio program, Bill O’Reilly had read passages from my column—at least that is what many people told me—and then had proceeded to call me either a moron or an idiot several times. He was more reserved on his TV program, but O’Reilly criticized me there also.

I cannot complain. I criticized him, and it was amusing for a basically unknown writer to be targeted by a nationally known celebrity. Really, how could I lose? But there certainly was a sense of anger and hostility—and an attempt at intimidation—from his followers that I have never felt before. It reminded me of what H.L. Mencken once wrote about how beating the drums for war caused even the opponents of war to doubt themselves.

I followed up with a column entitled “War brings out the purple people,” in which I documented this crude attempt to stifle war debate. I quoted from Mencken as well as from the great Old Right journalist John T. Flynn, who coined the phrase “purple people” in his book As We Go Marching. Nonetheless, I was subsequently called a leftist and a liberal and a commie. I am not used to being called those names.

Nationally, similar attempts by the neocon right to silence opposition became more common. The best-known effort was by David Frum, who tried to boot a host of Old Right luminaries out of the conservative movement. In a National Review cover article entitled “Unpatriotic Conservatives,” Frum launched a tirade accusing many honorable men (including the editor of this magazine) of being antisemites because of their antiwar stance.

That was in March, during the thick of the pro-war hysteria. Soon after, things calmed down. Frum’s charges were so reckless and so silly that few paid him any serious attention. Moreover, National Review no longer has the ability to kick anyone out of the conservative movement. The young editors who run it simply do not have sufficient gravitas to frighten anyone. O’Reilly was able to incite some callers to my newspaper, but I have not heard any angry responses to our continued opposition to the war—at least nothing comparable to the tone of earlier days. Their latest efforts to limit debate have simply failed.

When the BBC broke the story that the rescue of Jessica Lynch was largely Pentagon propaganda, the neocon squad sprang into action once again. Robert Scheer, the Los Angeles Times columnist whose leftism usually turns my stomach, did a fabulous job in covering the story.

“Eight days after her capture, American media trumpeted the military’s story that Lynch was saved by Special Forces that stormed the hospital and, in the face of heavy hostile fire, managed to scoop her up and helicopter her out,” Scheer wrote on May 20.

However, according to the BBC, which interviewed the hospital’s staff, the truth appears to be that not only had Iraqi forces abandoned the area before the rescue effort but that the hospital’s staff had informed the U.S. of this and made arrangements two days before the raid to turn Lynch over to the Americans.

Writing about the heated response on May 30, Scheer argued:

It is one thing when the talk-show bullies who shamelessly smeared the last president, even as he attacked the training camps of Al Qaeda, now term it anti-American or even treasonous to dare criticize the Bush administration. When our Pentagon, however—a $400-billion-a-year juggernaut—savages individual journalists for questioning its version of events, it is worth noting.

Forget about the ridiculous defense of President Clinton: Scheer had a point. As his column detailed, the neoconservative media and the Pentagon’s official flaks bloviated, but they never bothered rebutting the BBC story, or Scheer’s version of it, with the “facts.”

The good news is that the efforts at shutting down debate did not succeed for long. Even though U.S. troops might be in more danger now than they were during many phases of the war, the public seems to understand that widespread debate is healthy. The heightened sense of nationalism has subsided, and the widespread warmongering is failing.

Scheer continues to flail away at the war. The Register does not even get much comment on it anymore. O’Reilly has proved himself able to stir up a few malcontents to call a newspaper, but he has not accomplished much more than that. The media is as free and healthy as it has ever been, though that really is not saying much.

The major problem the media face today is a lack of diversity of views, even as editors embrace racial and ethnic diversity at ludicrous levels. There is little zeal in newsrooms for hard-hitting coverage, while much space is given to happy “community” stories that do not ruffle feathers.

I heard little complaint from journalists about the concept of embedding, which essentially made journalists mouthpieces for military units. Here is the introduction to a special news section printed in one newspaper:

They surged across the desert in their massive war machines, in a blizzard of smoke and sand, American Marines rolling northward toward war. . . . They were heavily armed as they rode across the desert, laden with M-16s and grenade launchers and tens of thousands of rounds of ammunition. . . . But the weapons were wielded by men, only human, and as hard and fit as they were after months and years of training, their bodies were vulnerable to pain. They could suffer—and in the coming weeks, they would.

Such prose might be pleasing to some, but it is not balanced coverage of the war. Efforts to support the local troops—which flow naturally from an emphasis on “community journalism”—often melded with the liberal emphasis on trusting the government. As a result, the public was spared a debate about the war until after it had ended. Even now, the toughest questions are going unasked.

In an effort to be all things to all men, journalism has lost its way. It is run by people who generally share the same view of the world. It has lost the hard edge for hard news, especially now that most newspapers are owned by a handful of national chains that have little interest in controversy or serious analysis.

Fortunately, the internet is helping to fill the void. Many links on different websites originate in traditional newspaper sources. Yet websites increasingly feature original pieces and are able to link to newspapers from all over the world, where the Zeitgeist is a bit different.

One day, perhaps, newspaper journalists will set aside the pointless hand-wringing and recognize that the public deserves (even if they may not want) a wide-ranging debate filled with controversy and diverse opinions on most issues—including foreign wars. If they do not get it delivered to their houses for 50 cents per day, they will find it for next to nothing on the internet.

Leave a Reply