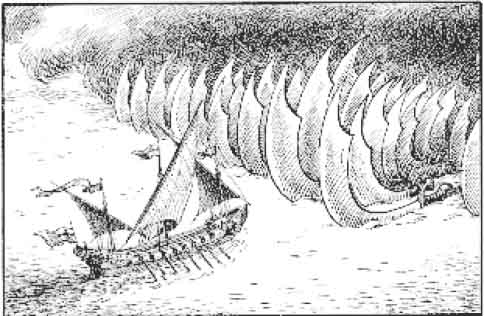

There are days and places in history when time seems to stand still and, in the space of a moment, the fate of future centuries is decided. At dawn on October 7, 1571, the spectacle would have made a strong impression on anyone who looked out at the waters breaking upon the straits that join the Gulf of Patras to the Gulf of Corinth, formerly called the Gulf of Lepanto, after an old fortified city that rose up from the sea. A gigantic fleet advanced slowly, with the south wind at its back. About 270 galleys and a massive number of light craft formed an enormous and threatening semicircle that occupied the seas from the mountainous coasts of Albania to the north and the shoals of Peloponnesus to the south. At the center of the advancing crescent, on the admiral’s flagship (the Sultana), a green banner waved in the breeze. The flag had been brought all the way from Mecca, and into its fabric the name of Allah was woven in gold 28,900 times. In September 622 of the Christian era, a man declaring himself the prophet of this deity had issued a call for the conquest of the world. The religion he founded summed up its mission in its name: Islam, submission.

Now, confronting the power of Islam, came a smaller fleet. Sailing into the wind, using only the power of oars, the ships lined up in the shape of a cross. The red and white flagship, the Royal, was flying a blue damask silk standard bearing the image of a crucifix. From the precious blood of this God made Man, crucified at Calvary, the Church developed and gave birth to a great civilization, the highest that has ever been known: Christendom. This civilization was under attack.

In 1453, after Mehmed II had conquered Constantinople—and, with it, the Christian empire of the East—the Turks had regarded the day of their universal dominion as imminent. In 1521, they gained possession of Belgrade; in 1526, they conquered Hungary and arrived at the gates of Vienna. In Italy, they had invaded and laid waste the entire southern coastal region.

Tripoli had already been taken from the Spanish; the island of Chios, from the Genoese; Rhodes, from the Knights who possessed it; and even Malta itself, the later seat of the Knights, would have fallen to the Turks had not Jean de la Vallette, grand master of the order, defended and saved the island with heroic valor.

In February 1570, a Turkish ambassador arrived in Venice, carrying an ultimatum from the Sublime Porte: Either give up the island of Cyprus to the sultan or there would be war. Venice had refused the ultimatum with disdain, but after 11 months of siege, the city of Famagosta on Cyprus fell on August 1, 1571. The terms of surrender guaranteed the lives of the remaining defenders, but once the Turkish commander entered the city, he gave orders that the commander of the Christian fortress, Marcantonio Bragadin, be skinned alive. His body was quartered, and his skin—stuffed with straw and dressed in his uniform—was dragged through the city. Terror reigned on the Mediterranean, and it seemed that Islam was arranging the same fate for all the Christians of Europe that it had inflicted on the Christians of Cyprus.

Sitting on the chair of St. Peter was a Dominican theologian, Michele Ghislieri, who had been made Pope at the beginning of 1566, taking the name Pius V. He appreciated the seriousness of the danger and understood that only a preemptive war would save the West. With grave and moving words, he exhorted the Christian powers to unite against the aggressors, and he made defense of Christianity the principal object of his brief pontificate.

Not everyone responded to the call. The expansion of the Turks had been made possible, in part, by the complicity of Christian powers such as France, which, in the name of Realpolitik, encouraged and financed the Turks in order to weaken France’s traditional enemy, Austria.

Nonetheless, thanks to the Pope’s prayers and exhortations, Spain, Venice, and Rome formed an alliance against the Turks on July 25, 1570. They were soon joined by the duke of Savoy, the Republics of Genoa and Lucca, the grandduke of Tuscany, the dukes of Mantova, Parma, Urbino, and Ferrara, and the Sovereign Order of Malta. This alliance was a prefiguration of Italian national unity, though on a Christian basis—the first major Italian political and military coalition in history.

Don John of Austria was chosen to head the Christian League. This young man—only 25 years old—was the natural son of Charles V and the half-brother of Phillip II of Spain. The pontifical fleet, assembled with the help of the Knights of San Stefano, was commanded by Marcantonio Colonna, duke of Paliano, to whom the Pope entrusted the Church’s banner. The Holy League was officially proclaimed in Rome at St. Peter’s Basilica. After leaving their rendezvous point at Messina, the Christian fleet sailed for 20 days before attacking the enemy at 11:00 A.M. on Sunday, October 7, 1571.

The battle lasted five hours, and the outcome was decided in the center of the formation where the flagships were grappled together, forming a floating battlefield on which attacks were followed by counterattacks, until the regiment of Sardinian Arquebusiers succeeded in unleashing the decisive attack. Ali Pasha, the Turkish commander, was shot dead, and aboard the Sultana, the Crescent was hauled down and the Cross hoisted up.

Among the many who covered themselves with glory on that day were the noble houses of the Colonna and the Orsini; the count of Savoy, who fell in battle; the 23-year-old Alessandro Farnese, destined to become one of the greatest condottieri of the century; and Giulio Carafa, who, after being taken prisoner, managed to free himself and take over an enemy brigantine.

The Venetians paid the greatest tribute of blood. The Venetian provveditore, Agostino Barbarigo, who commanded the left flank of the Christian formation, fought on—with an arrow sticking out of his left eye—until his strength left him; Sebastian Venier fought with his head unprotected and wearing slippers, because they afforded a surer footing on deck. At 75 years old, he managed the catapult with a sailor’s help. Overwhelmed by numbers, he was helped by the galleys of Giovanni di Loredan and Caterino Malipiero, who fell in the struggle.

With equal courage, 12-year-old Filippo Pasqualigo received the last words of his brother, shot dead by the Turks. Antonio Pasqualigo was commander of the galley the Crucifix. He had brought his younger brother with him to teach him how Venice was to be served. This was the way they were reared, those whom the people recognized as “Venetian patricians.” This was the way the Italian aristocracy, renowned for their valor throughout Europe, fought in those days.

An eyewitness, Ferrante Caracciolo, describes in his Commentaries the spectacle of that afternoon:

The Sea was full of corpses, tables, clothing, Turks who fled by swimming, others who drowned; many shipwrecked vessels, and colored crimson from so many killings; ships that looked on fire, others that went to the bottom, the rocky coast full of Turks who were fleeing and at whom our galleys were firing cannonades at a furious rate, so many little boats of the enemy were beached making a horrifying and frightening spectacle for the losers, but a sight that brought our men, on the contrary, joy and delight.

At the end of the battle, the league had lost more than 7,000 men, as well as about 20,000 wounded. The Turks lost more than 25,000, and 3,000 were taken prisoner. The name of Lepanto had entered into history. For the first time in a century, the Mediterranean was free. The decline of the Ottoman Empire had begun.

In the afternoon of October 7, 1571, Pius V, who had multiplied his prayers to the One Who had always succored Christians in their times of crisis, was going over the accounts with several prelates. Suddenly, he stood up and went over to the window, staring as if in a trance; returning toward the prelates, he exclaimed: “Let us no longer occupy ourselves with business, but let us go to thank the Lord. The Christian fleet has obtained victory.” The Pontiff attributed the triumph of Lepanto to the intercession of the Virgin and expressed his will that they add, in the liturgies at Loreto, the invocation “Auxilium christianorum.” Even the Venetian Senate decided to accord the Virgin the principal merit for the victory; on a panel in their meeting room, they had painted these words: “Non virtus, non arma, non duces, sed Maria Rosari, victores nos fecit”—“It was not courage, not arms, not leaders, but Mary of the Rosary that made us victors.”

Some might ask if Pius V, instead of promoting and undertaking a war, would not have done better to stretch out the hand of friendship to Islam, seeking peaceful coexistence through dialogue and toleration. For those who favor this option, Lepanto becomes an historical memory to eliminate, an episode to forget. They believe that the choice before us today is between fanaticism, which finds its expression in terrorism, and the relativism—modern and postmodern—that deceives us into thinking that we can avoid war by not speaking its name.

To reduce radical Islamism to terrorism or to the deliriums of a psychotic, however, is to insult both Islam and our own intelligence. Radical Islam is an interpretation that is coherent and widely spread throughout the world of Islam. It may not be the majority opinion, but it is strong precisely because it is radical and coherent, and it will, therefore, expand within Islam, which even in its moderate version has always had as its goal—derived from the Koran—the subjugation of the entire world to the word of Allah. This is a teaching that characterizes all Islam, before and after Lepanto.

Islamic terrorism is simply a strategic variant of the broader project of conquest whose ultimate goal is the Islamicization of our society. The gentler and more effective means of reaching this goal are demographic increase and the gradual introduction of Islamic law, the peaceful conquest of Western society according to the formula recorded years ago by Bishop Bernardini of Smyrna: With your laws we shall conquer you, with your might we shall dominate you.

If St. Pius V is going to be accused of fundamentalism or fanaticism, that accusation would also have to be extended to Our Lord, who claimed to be God incarnate, and to His holy apostles, who claimed to announce to the world the truth of salvation, absolute and without compromises. The apostles and the missionaries who followed them did not use weapons; they firmly believed in the message they announced, its superiority, and its power to assure eternal life to our souls and a relative happiness on earth to men. This earthly happiness, relative because it is accompanied by Original Sin, was called “Christendom.” It was to defend this threatened civilization, not to impose the Faith upon the world, that those who fought at Lepanto took up arms.

In praising their heroism, we are not launching a holy war, only recalling that we have a right to legitimate defense, that we have something worth defending, something worth more than life itself, because it is a spiritual good that belongs to preceding and future generations: Our Faith, our culture, and our civilization. The “clash of civilizations” was not invented by Samuel Huntington; it is a reality, whether we wish it or not. To acknowledge its existence is not the same as to desire it, and if we were to eliminate the phrase from our language, we would not so easily eliminate the reality.

It would be wonderful if we could avoid war by simply refusing to label an aggressor as “the enemy.” Unfortunately, in a war of defense, it is not up to us to choose the enemy: The enemy chooses us. The gates of the gulag and of concentration camps stand open to receive all those who refuse to defend themselves, but those who choose to fight may hope for victory. For this reason, Christian combat, which is a spiritual attitude more than anything else (although it includes the possibility of legitimate defense and just war), belongs to the tradition of the Church.

The Church has never professed pacifism. The total pacifist—someone who rejects even a just war—has forgotten that there are some evils that are more profound than physical and material ones, and he has failed to distinguish between the ruinous consequences of war on the physical plane and the causes of war, which are moral and originate in the violation of order—in a word, sin. Every Christian must desire and work for peace. In a 1948 radio message, Pius XII explained that the call to peace is based on divine law. But peace, as Saint Augustine taught, is tranquility of order; and this presupposes a just moral and social order, or even a Christian order. It is a natural order in which the laws of reason and nature, imprinted upon the human heart, are respected. This justice represents a common good that we may not renounce, because the renunciation of this common good, the negation or the destruction of this natural and Christian order, has as its consequence the unhappiness of men on this earth and the eternal destruction of their souls.

The goal of peace, explained Pius XII, is the protection of humanity’s goods insofar as they are the creature’s goods, some of which are so important for the life we share as human beings that “their defense against unjust aggression is, without doubt, completely legitimate. . . . A people that is threatened or already victimized by unjust aggression, if it wants to think and act in a Christian manner, cannot remain in a state of passive indifference.” The Christian does not fight because he loves war; he fights because he loves peace—true peace, just peace, the peace that requires in its own defense a just war in accordance with Christian moral theology. According to just-war theory, war is illicit when it is waged without just cause, but for those whose cause is just, war is not only licit but even, in certain cases, mandatory.

Today, however, an internal enemy threatens us. This enemy is first and foremost a mental attitude that surrounds us, even in Catholic circles—if not especially in Catholic circles. Radical Islam is not wrong because it professes truth; it is wrong because it professes error. If, in opposing error, we uphold relativism—a vision of the world in which there is room for every error, because the whole idea of truth is to be jettisoned—then we are committing an error even greater than that of the radical Islamicists.

This is the error of those who claim that the age of Lepanto and the Crusades is over and, with them, the spirit of Christian combat that presupposes a vision of the world based on the primacy of the absolute truth that is worth living and dying for: the truth of the Gospel. In its place, they offer a vision of the world that tells us that nothing exists that is either absolute or true, that everything is relative to the time, the place, and the circumstances.

This relativism leads us to avoid conflict and polemics at all costs—to give up testifying to what is true, good, and just. This apathy is the direct opposite of the spirit that animated the Christian martyrs, who gave us an example (in the words of Pope John Paul II) “of a life totally transfigured by the splendor of moral truth.” It is not death that makes the martyr, says Saint Augustine, but the fact that his actions are in conformity to truth, that his suffering and death are directed toward justice. Martyrdom is the highest embodiment of the virtue of fortitude, whose essence lies in the disposition to suffer in order to realize the good. “For the sake of the good,” says St. Thomas Aquinas, “the brave man exposes himself to the peril of death.”

As heirs of Lepanto, we should recall the message of Christian fortitude which that name, that battle, that victory have handed down to us: Christian fortitude, which is the disposition to sacrifice the good things of this earth for the sake of higher goods—justice, truth, the glory of the Church, and the future of our civilization. Lepanto is, in this sense, a perennial category of the human spirit.

Today, the West—what was the Christian West—is undergoing an attack without precedent, not only from without but from within. What remains of Christendom deserves to be defended, because it is from this remnant that a different and better future will be constructed for the generations to come.

Leave a Reply