The regime we live under—the regime of the United States Constitution—began with a set of clear understandings. One was that the federal government was to be the servant of the people. It was to be confined to the specific powers the people “delegated” to it, pursuant to the general welfare and common defense of the United States. If it exercised powers the people had not delegated to it, it was “usurping” power and committing “tyranny.” A federal government was, of course, a compact among the sovereign states, as opposed to a “consolidated” or centralized government that was itself sovereign.

Few Americans understand this kind of talk today. Words like “delegated” and “consolidated” are known only to people who set out to build more powerful vocabularies. You can hardly explain the difference between “federal” and “consolidated” government to the products of modern American education, because when they hear the word “federal,” they assume it means the same thing our ancestors meant by “consolidated.” For all practical purposes, “federal” is just a fancy synonym for “big.”

The idea of restricting government to “enumerated” powers—a written and finite list—is equally alien to today’s American. The only remedies he can think of for big government are term limits and a balanced budget amendment. The lucid and shared philosophy of the Founding Fathers, imperfect as it was, has also become unintelligible to today’s American, who knows only a set of slogans labeled “liberal,” “conservative,” and “moderate.” Of course there are wide areas of consensus; if you are outside those areas, you are an “extremist.”

One of the things we can all agree on—unless we are extremists—is that America has a mission abroad: “world leadership.” Both parties and all stripes of pundits agree on that. We must lead the “international community” in keeping peace, deterring “terrorism,” and securing “human rights.” Along with these lofty goals, we must defend our “vital interests” around the world.

To deny this part of the new American creed is to be labeled an “isolationist.” We must never forget “the lesson of Munich,” which our new Secretary of State considers her formative lesson, as opposed to what some people call “the lesson of Vietnam,” or what might be called “the lesson of Sarajevo.” Isolationism led to World War II. Never mind what led to World War I.

I grew up in a family in which Franklin Roosevelt was only a notch below God. My father and uncles had all fought in World War II, and it was unpatriotic to entertain the faintest doubt that the war had been righteous. Not that we had any arguments about this; it was a given. I never doubted it until I was a middle-aged man. And in doing so I was typical of my generation, except that in my ease, doubt eventually set in.

Today I marvel at the consensus in favor of that war. It killed 400,000 young Americans in foreign places. It robbed a generation of men like those in my family of a normal youth. It involved the United States in an alliance with the worst tyranny in Western history. It was chiefly waged against civilians, with American planes bombing huge cities without mercy. It ended with communist rule over ten Christian nations. It created nuclear weapons—and we used them. Those weapons were soon aimed at us, putting us in far more peril than we had ever dreamed possible. And Poland, over which the war had started, ended up a possession of one of the original aggressors.

There is a deeply touching painting by Norman Rockwell titled “War News.” It shows four middle-aged working men in a diner, huddled around a Philco radio. When I see those men, I see my family—ordinary people who voted for Roosevelt during the Depression and who then, a few years later, spent each evening wondering if their sons were dead on some Pacific island. And never did they cease to worship Roosevelt.

But World War II, even more than the Civil War, remains the holy war of the American establishment—the event that gave legitimacy to arrangements of power absolutely opposed to the arrangements established by the Constitution. It not only completed the consolidation of domestic power in Washington, but turned Washington into the capital of an enormous empire, which itself consolidated during the Cold War. Of course consolidation is never quite complete, and though there are no more worlds to conquer, there are still a few parts of the world we have not fully subdued.

Americans do not like words like “conquest” and “empire,” so these terms are not part of the official vocabulary. After all, our rulers led us into war by telling us that the Kaiser, Hitler, the Japanese, and the Soviets were bent on “world conquest.” So we speak of “leadership,” “defense,” and “promoting democracy.” Everything we do, everywhere, is “defense.” Even the Department of War has been rechristened the Department of Defense.

American military action is now defensive by definition. No matter how many troops we place abroad, no matter how far from home, no matter how many people we kill in their own homelands with advanced weaponry they cannot hope to match or resist, we are merely “defending” ourselves. Why can’t those foreigners understand this?

It is odd that we attach such opprobrium to “isolationism.” We Americans are a psychically isolated people who, in our dealings with the rest of the world, are peculiarly uninterested in other people. We have very little curiosity about how the world looks from other places. When we fight a war, we do not even ask ourselves why there is another side. That may have something to do with why we are becoming so widely hated—a fact that seems to surprise us.

On the one hand, we are told that military intervention abroad is in our “national interest.” But if we conclude, after weighing costs and benefits, that intervention is actually against our interests, we are accused of “isolationism” for failing to support it anyway. It seems that intervention is our duty, no matter what it costs us.

We have come a long way from “the common defense of the United States.” This originally meant that if one of the 13 states were attacked by a foreign power, the other states would consider themselves under attack too, and act accordingly.

Foreign policy is a lot less literal-minded than it used to be. Who knows what “vital interests” are? We are told that our “vital interests” are at stake everywhere in the world. George Bush specified Iraq, but never explained why—or rather, explained too often: the reasons Bush gave for the war included the evil of aggression, oil, and “jobs.”

To be literal-minded about it, a “vital interest” is one on which your survival depends. In that sense, the survival of the United States has never been threatened except by Russian missiles, which came into existence, ironically, because of the United States entry into World War II on the Soviet side. Any “threat” posed by Germany and Japan in 1940 was as nothing compared with the threat posed by our Soviet “ally” ten years later. I doubt that even Franklin Roosevelt would have entered that war if he could have foreseen its results.

So why did we fight World War II? In terms of real interests, it is hard to explain—especially if we mean the interests of ordinary Americans, as opposed to a ruling elite and special interests. We are given the ex post facto reason that the Nazi regime was absolute evil, which puts foreign policy into the realm of metaphysics. That could hardly have been the real reason. My grandfather gave my father an earthier explanation: “You can’t have two bulls in the same pasture.” That may not be a sufficient reason either, but at least it makes some sort of sense.

Switzerland has recently faced what some people have called its greatest foreign policy crisis since World War II: the demand for the return of Nazi-confiscated wealth, deposited in Swiss banks, to its rightful owners. If this is its worst crisis over the last half-century, one can only envy Switzerland. That little country is also under renewed attack for having stayed out of the war. Yet it is none the worse for wear for its notorious neutrality; it spared the lives of tens of thousands of its sons. You might think it deserves some credit, or at least human consideration, for that. But one hardly dares to ask in public: Why should the Swiss have fought? Apparently the Swiss government actually identified its national interest with the good of its people. Whatever others may say, I honor Switzerland for keeping its sanity. It remains a serenely civilized country. But of course we seldom ask whether the Swiss may know something we do not. For example, if Switzerland, in the midst of belligerents, could remain aloof from the war, surely the United States might have done so. Switzerland has only mountains to buffer it; we have two oceans. Why not use them?

Today the American government is still looking for trouble. It is currently trying to expand NATO to include countries bordering on Russia, but not Russia itself; and Mrs. Albright has tried to explain to the Russians that this policy is not anti-Russian. Certainly not. No more than it would be anti-American for the Russians to form a military alliance with Canada and Mexico, and to place troops on our borders. Again our rulers show the American trait of incomprehension of other perspectives.

Russia is still a potentially dangerous country, with a huge nuclear arsenal. What on earth is gained by provoking it now? Its communist ideology is dead; its problems are local and internal; it has no natural reason to be our enemy anymore. Yet our rulers want to give it a reason gratuitously. Are they insane? If not, they are criminally irresponsible.

I used to try to understand the sophisticated rationale for American foreign policy that I was sure existed. It took a long time for the truth to dawn on me: American foreign policy is an insult to the intelligence. Yes, highly sophisticated people try to shape it, and some of their machinations and rationalizations are extremely clever; I’ll give Henry Kissinger that much. But it is as futile to seek integrated rationality in American foreign policy as to seek it in our government’s domestic policy. Both are chaotic. If they have a common denominator, it is the habit of accumulating power, of starting and continuing on risky and expensive courses whose final consequences no man can foresee.

Whether your literary taste runs to Hayek or Hamlet, the lesson is the same: the future cannot be controlled. Michael Oakeshott has shown the inherent futility of “rationalism in politics.” Rationalism of the kind Oakeshott described may be discredited in domestic politics—socialism is a dead ideology—but it survives in the current attempt to build a “New World Order” through international conferences, treaties, paper currencies, trade agreements, and the like, along with sporadic military intervention of the kind the United States has engaged in from Haiti to Somalia to Bosnia to Iraq.

I yield to nobody in my contempt for our news media, which do their best to support the ruling elite. Far from a critical “adversary press,” we rely for information on a courtier press that wants to be part of the action and shape public policy—an ambition that corrupts the avowed purpose of keeping us informed. And yet, for all its faults, the press, including television, tells us more than it intends to. Anyone who watches carefully will lose any awe, or even trust, he once felt for our rulers. They relentlessly expose themselves as venal, small-minded power-seekers to whom it is sheer madness to entrust our fate. No amount of favorable press coverage can conceal that. Our Presidents, our justices, our congressmen are made of the same stuff: Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Newt Gingrich—I’m starting at the top of the line of succession—Ted Kennedy, Al D’Amato, Pat Schroeder, Barney Frank . . . but why go on? These may be among the worst; but who are the best? Is there anyone in public life today you really admire? More to the point, do you trust the aggregate of these people to send our sons abroad to fight in worthy causes? We cannot even trust them to keep their hands out of the till. As for acting on any noble or honorable public philosophy, the idea is ludicrous. There is no point in debating principles with such people, any more than with a Mafia don.

But our current rulers are the natural residue of a long history. A country that has chosen such “great” leaders as Lincoln, Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt has pretty well decided that its future Jeffersons will have to find occupations outside politics: a centralized welfare state operating a global empire has closed off Jeffersonian options. How many Johnsons, Nixons, and Clintons do we have to endure before we realize that they are not anomalies? Who is fitter than Bill Clinton to lead this kind of country at the pinnacle of “world leadership”?

Such is the “leader of the free world.” We have produced a system that guarantees that men like him will rise to the top. It is bad enough that they exercise enormous leverage over a quarter of a billion people within our borders; it is horrifying that they should exert similar impact on the rest of mankind. We should feel disgust for our rulers, but they are by no means the worst feature of American society today. American culture itself is now so completely degraded—so self-evidently foul—that we can only be embarrassed and shamed by its global influence. One feels that it should be placed under some sort of international quarantine.

Our rulers and cultural leaders share one remarkable trait: they are seriously alienated from Christian culture. They consider it a positive virtue and duty to uproot popular Christian traditions. The new movie The People vs. Larry Flynt celebrates a pornographer and the Supreme Court decision that “expanded our First Amendment freedoms.” The partnership of a pornographer (who himself is oddly like our President) and the judiciary aptly symbolizes our decline.

Conservatives rail against the courts for their support of such evils as pornography and abortion, but it is not just the content of recent jurisprudence that matters. It is that the federal judiciary has been part of the broader assault on federalism. We are taught that the Supreme Court furnishes a check on the other two branches of the federal government. But nearly all of its important decisions over the past half-century have overturned state, not federal laws. Far from checking federal usurpations of power, the Supreme Court has played a vital role in the whole campaign of usurpation. In the name of separating church and state (according to a fraudulent interpretation of the First Amendment), it has de-Christianized America at the state and local levels. Its message to every town in the country is that it may not rule itself according to its most sacred traditions. In acting thus, the Court is not merely “legislating,” as its accusers say; even more important, it is centralizing power in the name of the Constitution that was supposed to protect us against “consolidated” government.

The Court’s critics are closer to the mark when they speak of the “imperial” judiciary—but the judiciary does not aspire to independent power; it supports the Washington-based empire by weakening all the rival centers of power that once constituted the federal system. The federal judiciary is actually anti-federal. Because traditional popular culture is, or was, deeply Christian, the country could only be de-Christianized by edict from a single center of power, preferably by unelected officials. This role was quietly assigned to the judicial branch, which has nothing to fear from the voters.

Meanwhile, American influence abroad has also made war on local cultures and traditions. Commercial movies and music have insulted sexual morality, and foreign “aid,” including subsidies to population-control groups like Planned Parenthood, have promoted contraception and abortion in defiance of local religious codes and deep-rooted mores. It is by no means only America’s support for Israel that causes Muslims to feel that this country is making war on Islam. (Only in Bosnia has the United States taken the side of Muslims—perhaps because their enemy, this time, is Christian.)

When local populations fight back with the only weapons available to poor people who lack advanced weaponry, our rulers and their courtier journalists damn and dismiss this reaction as “terrorism” and “anti-Americanism”—the counterpart of the “extremism” of those Americans who also see the American government as their deadly enemy.

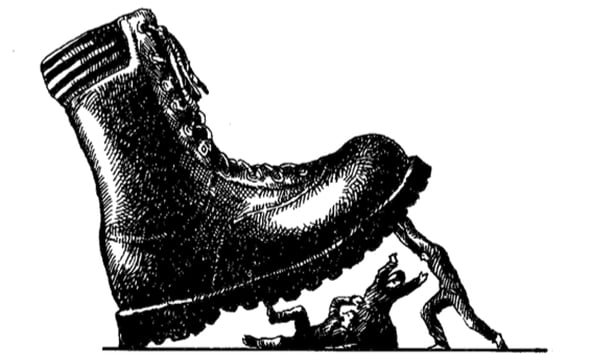

Unfortunately, our government specializes in making enemies, at home and abroad. As George Washington said, government is not reason or persuasion, it is force. The bigger it grows, the more it is forcing or forbidding people to do things against their will—whether they are taxpayers, worshipers, businessmen, or cigarette smokers. And the more it does such things, the more it pits itself against those it rules. Eventually it reaches a point of essential alienation, where it can no longer pretend to represent the governed.

The American government is now the most powerful human organization that has ever existed. It has made a stupid habit of exercising power arbitrarily, uninhibited by moral or constitutional principle. It is not a conspiracy masterminded by some cunning genius at the center; it is a system of power which large numbers of greedy and ambitious people have learned to use. It has ceased to be a problem for Americans only; it has become a problem for a large part of the human race.

Last summer the neoconservative Weekly Standard ran a cover story attacking Bill Clinton’s foreign policy under the title “Is This Any Way to Run a Planet?” Running a planet! Clinton’s foreign policy, you see, was insufficiently interventionist for the Standard. And in February it ran a whole issue on the menace posed by China (just before the death of Deng Xiaoping, as it happened). I was amused to see that its lead editorial noted with alarm that China is increasing its “defense” spending. Well, one might ask, why shouldn’t China defend itself? But obviously the writer meant to imply that China has aggressive designs, and out of long habit he used the word “defense” in the American style, in which all military spending is called “defensive.”

The same editorial went on to accuse China of wanting to replace the United States as “the dominant power in East Asia . . . and the world.” I wondered if the Standard assumes stupidity in its readers, or merely reflexive agreement. Why should the United States dominate either East Asia or the world? And at what cost and risk? Such questions are not to be asked. Nor is the question whether American hegemony over the whole world is morally right or desirable.

Lately the Standard and other neoconservative tracts have also sounded an alarm against “anti-Americanism”—among American conservatives who have finally recognized their own government as their enemy. Apparently the American government is entitled to our unconditional love. Soon, no doubt, the neoconservatives will be accusing the conservatives of giving their loyalty to a foreign power.

But the Founders of this country would not recognize the present government as their creation. We need not idealize them in order to recognize that the regime we live under now has severed any real connection with the original Republic, with its principles, its political culture, its love of peace and good relations abroad free of “entangling alliances.”

At home and abroad, this government has wildly outrun any possible rationale for its power. It is something every American should be both afraid of and ashamed of. A patriotic American today ought to be “anti-American.”

Leave a Reply