Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, recently published an article in Foreign Affairs which encapsulated the agenda of the globalist elite for the incoming Biden administration, should the former vice president be sworn in on Jan. 20.

“When he first enters the Oval Office,” Haass writes, “President-elect Joe Biden will be greeted by an inbox that can only be described as daunting. There will be a seemingly unlimited number of domestic and international challenges that call out for his attention.”

Haass claims that Biden and his team need to follow the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, which means “repairing the world”: “This world is in dire need of repair,” he concludes, “a process that will take time and inevitably meet with uneven success.”

These assertions are inaccurate, and the implied call for America’s full-spectrum engagement is dangerous. The world is relatively stable now, arguably more so than at any time since the middle of Barack Obama’s second term. Let us be specific.

In Europe there are no flashpoints requiring immediate—let alone sustained—U.S. attention. Eastern Ukraine is remarkably peaceful following the ceasefire which came into force on July 27. Since then, there have been fewer than a dozen total combat losses. If Biden does not send lethal weapons to Ukraine, the region would likely remain stable. To follow through on his campaign promise to arm Ukraine would encourage nationalist hardliners in Kiev to advocate yet another attempt to reconquer the Donbas by military means, and its likely failure would lead to demands for greater U.S. involvement.

Tikkun olam has the implied dual meaning of not making things worse than they are. In the former Soviet space the world is best served by Biden doing nothing. It is to be feared that he would be unable to resist the temptation to do something.

Elsewhere, the dispute between Greece and Turkey over their exclusive economic zones (EEZ) in the eastern Mediterranean is under control. The European Union for once seems to have developed a common foreign policy position supporting Greece. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s audacious appetite has been curtailed thanks to this common front which also includes Israel, Egypt, and Cyprus.

Erdoğan has also failed to neutralize the Kurds east of the Euphrates in northern Syria, where no significant fighting has taken place in months. In fact, the whole of the Middle East presents no pressing problems right now. The peace treaty between Israel and the United Arab Emirates is yielding economic fruits, with UAE’s Etihad Airways starting daily flights to Israel in March. Soon after the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan also agreed to normalize relations with Israel in similar agreements.

Iran is too preoccupied battling the pandemic to foment regional mischief. It is also eager not to alienate a new, less belligerent administration in Washington. Across the Shatt al-Arab, Iraq has recorded fewer terrorist incidents over the past quarter than at any time since the Iraq War started in 2003. In Yemen, the war initiated by Saudi Arabia has effectively ended with a Houthi victory. In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has all but destroyed the Islamic insurgency in the northern Sinai.

Erdoğan has tried to recover some of his eroded prestige by encouraging Azerbaijan to launch an attack on the Armenian-inhabited enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. The operation was a partial military success for the Azeris, but in the end a diplomatic solution was found through the intervention of Russian President Vladimir Putin. With Turkey’s tacit agreement, Russia will underwrite the new status quo in the southern Caucasus with 2,000 armed peacekeepers, the first time Russian troops will be based in Azerbaijan since the collapse of the USSR. Another crisis has been resolved without American input.

Looking further east the outlook is no less encouraging. To his credit, Donald Trump will effectively wrap up the endless American presence in Afghanistan over the next six weeks, with no tangible harm to U.S. national security interests. The key lesson of Afghanistan is that we should stay away from far-off countries and people of whom we know little. When the last GI leaves—in January 2021, or in a hundred years—Afghanistan will revert to its usual Hobbesian condition. No American soldier ever should have died there. The fact that nearly 2,400 have died is a crime and a mistake.

More significantly, there have been no serious clashes in the Himalayas between India and China since last summer. Even in their aftermath, the notion of India as a new bulwark against China has not captured either country’s imagination. It may be revived under a potential Biden administration, however, as indicated by Biden’s strange and unnecessary statement of support for Japan’s claim over the Senkaku Islands, in view of the 1960 U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty.

There is no sense in staking America’s future on whose flag flies over some godforsaken islands in the East China Sea, except for members of the Repairing-the-World Cult. This group has raised its ugly head again in the wake of Biden’s alleged victory in November.

Trump’s attempts to turn America into a normal, non-missionary nation appear to have been thwarted. For the next four years at least, neither the U.S. nor the world would be safe from the insane urge to “engage” America in pursuit of repairing the world.

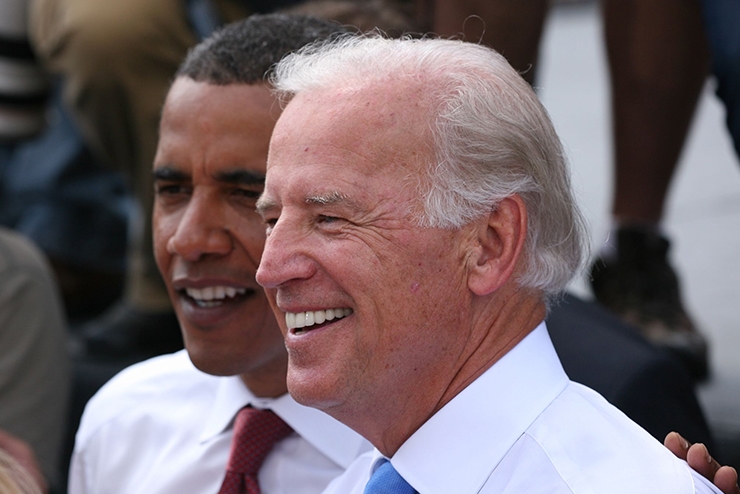

Image Credit:

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons-Daniel Schwen, CC BY-SA 4.0

Leave a Reply