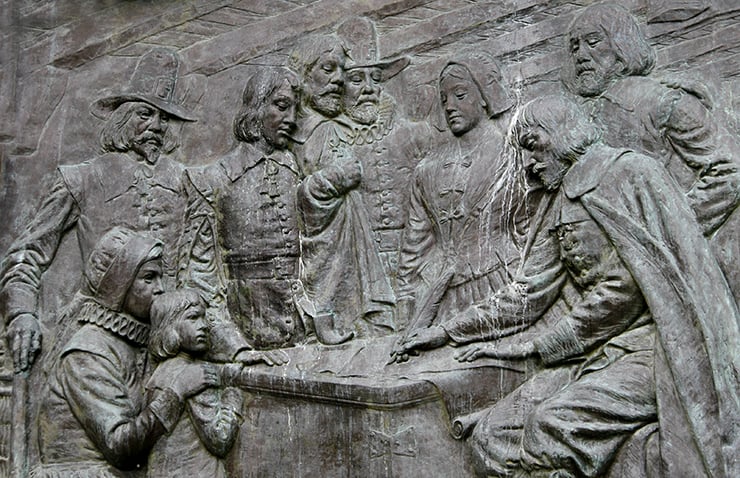

It’s 1620. A cold November wind whistles through the rigging of a Dutch fluyt anchored in Massachusetts Bay. Below deck religious separatists, merchant adventurers, and soldiers of fortune are hard at work … lawyering.

Having set sail in the Mayflower for a new Promised Land over a month earlier, they have arrived too late in the year to make camp on shore so they have chosen the shelter of this ark for the winter. While they are still by maritime conventions under the rule of their captain, Christopher Jones, there is nonetheless a first order of business for this fractious community of brave souls: a charter to govern themselves.

They begin,

In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are underwritten, the loyal subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.

They do not call upon the authority of King James specifically; rather, it is only derivatively in professing they are loyal subjects. They explicitly call upon the authority of God.

The separatists among them are not reformers of the Church of England. As separatists, they had already left that intermediary and have taken a next step in the reformations cascading from the teachings of Martin Luther and John Calvin. In their loosely agreed doctrines they have established for themselves a direct link to God Almighty.

They are sovereign over their own consciences, and while remaining loyal to the sovereign they have physically abandoned, they are taking actions which imply sovereignty over themselves politically.

Having undertaken for the Glory of God and advancement of the Christian Faith and Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the First Colony in the Northern Parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually in the presence of God and one of another, Covenant and Combine ourselves together in a Civil Body Politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute and frame such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions and Offices from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience.

Thus the Pilgrims consented to their form of government.

This Thanksgiving I will be thinking about this, and also my gratitude to Alex Newman for his reply to my essay“It’s Time to Change the Constitution.”

In his “Constitutional Convention Would Open Pandora’s Box,” Newman warns of “catastrophic” consequences of an Article V convention of states. “The future of American’s God-given rights hangs in the balance.” On this last point Newman and I are in agreement, and in general accord with the 41 signatories of the Mayflower Compact.

But after that everything falls apart, quite literally for Newman. “Forces” are “champing at the bit to change—or even trash [the Constitution]—and forever burn the bridge that could lead the United States back to the liberty, prosperity, and peace made possible by that precious Constitution for well over two centuries.” It’s a “massive gamble”; “… it could be the final nail in the coffin for the free United States of America; and “[with] this one mistake, the amazing heritage of the nation could go up in smoke forever.”

My advice to Newman, and to those who share this fear is: Don’t panic. Amazing as it may seem upon first reflection, the Constitution itself is not the sacred heritage to be preserved at all cost. Consent is that sacred heritage.

First, let’s discuss some things about the existing Constitution. Then, let’s discuss our sacred heritage, which will bring us back to the beginning.

Newman readily admits the Constitution is not working as intended. He also admits that the old willingly disregard the Constitution, and the young barely know of it.

In so doing he raises the question whether we Americans are bad people, incapable of governing ourselves. But I do not think Newman desires the obvious alternative for bad people, rule by one man—a Caesar, red, blue, or purple—or even by a cabal of a few men.

Rather Newman claims the Constitution’s restoration lies in enforcement, in making people “obey.” Epistolary work for the naughty on the virtue of obedience is for naught. And Newman offers no other mechanism for enforcement, nor does he point to any provision of the Constitution adequate for such enforcement.

The Constitution leaves its enforcement to all its officers but in practice it falls chiefly to the courts and the executive. But that leads to the trap we are in today: battling over the Supreme Court in death watches and fights over nominations, confirmations, court packing, and court purging (now in vogue with the attacks on conservative justices, most sharply, Justice Clarence Thomas). Neither has this worked nor could it fix a more fundamental problem: the alienation of the people from their charter. The elements of consent in this process are oblique, fragmentary, and obscure, especially as compared to the adoption of a charter through a ratification process, which is a direct, whole, and obvious act of consent. And the fighting, among other things, has subjected the American people to the indignity of the periodic personal destruction of their justices. In so doing, this process has taught the American people to disrespect the Supreme Court and otherwise to be personally destructive as a regular part of our politics. Thus we can dismiss this constitutional remedy of enforcement as ineffective and, if we are candid, malignant.

Newman maintains that the Constitution has no real “defect.” He does not examine this proposition. If a charter is not functioning as intended might that be a consequence of its structure, and the tendencies that structure fosters? Hamilton, writing as Publius, argued in the Federalist that the structure of the Constitution obviated the need for a bill of rights. Why should one not entertain the thought that the structure of the Constitution, when combined with massive growth in population (of varied provenance and legality), increased foreign policy burdens, and changes in media, tends to effect an infringement of rights and corruption of duties?

The bicameral system of our legislature, in conjunction with a separation of the executive and the legislative powers was intended, according to the Federalist, to make it difficult to pass legislation not designed for the common good. George Washington had hoped there would be no party system at all, but the incompetencies of the Constitution for majority formation quickly led to the creation of one. Without a functioning party system for broad majority formation the Constitution arguably cannot produce good laws. That is, with split-ticket voting, thin majorities, and divided, partisan government, the Constitution produces legislative incompetence. Could that not be a cause, in part, of the growth of the administrative state? In the absence of competent legislative output from Congress, other institutions fill the void, not just from arrogance and degenerate ambition, but also out of necessity. Urgent national needs otherwise cannot be met.

Another defect may well be that the Constitution leaves to Congress to decide the number of representatives by act. This number has been set at 435 since 1911, and permanently affirmed in 1963. Now the House of Representatives is the least representative popular house of all the significant contemporary republics.

Having an unrepresentative popular house has consequences, beginning with the dilution of its popular character. With more than 700,000 constituents per representative (comparable governments have less than 200,000), our popular representatives, as a practical matter, are accessible only to an unctuous and selfish class of donors.

Representatives have expensive campaigns to run every two years, they are paid little, must maintain a residence in their district and in D.C., and have influence over billions of dollars in spending. You could not design a better mousetrap for corruption. It is nonetheless obvious that our representatives see some virtue in this arrangement because they make no effort to change it, and they rarely leave the sparsely compensated office willingly. Seriousness obliges one to think of ways to change this.

The Senate is not much better. First, if the founders thought small-state, large-state issues were difficult to bridge in 1787, could they have anticipated the effect of westward expansion and the failure to populate the many states made from the territories there. One can lament the raising of this point because it touches on a great sensitivity—red state conservatism has depended on western state power with Wyoming, the Dakotas, Montana, and Alaska. However, blue state liberalism also depends on small-state power in the East with New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Delaware, Vermont, and Maine. After decades of policy favoring the coasts and disfavoring the exploitation of the interior, these are issues worth considering.

In any event, the Senate—faithful to its Latin root senex, meaning old—is host to many people who are very long in the tooth. Who can watch the Senate minority leader “freeze” in geriatric cognitive weakness another time and say there is nothing to consider here from a fundamental law point of view?

On the scope of the legislative power, how does one address the unlimited elasticity of the commerce clause and the taxing power other than through a convention? Perhaps a convention can do nothing to cure such things. Or maybe it could produce a compromise rescuing some portion of federalism. Anything would be superior to essays pointing wistfully but futilely to the 9th and 10th Amendments.

There can of course be no assurance that a convention of states would not be a disaster. That, however, is unlikely, and therefore, considering the dysfunction both Newman and I agree exists, it is a gamble well worth taking. The likely downside is nothing happens at all: a convention fails to produce anything ratifiable. Even in that downside there is an upside: at least these things will have been considered in a context separate and apart from our day-to-day incompetent political discourse.

As I said in my original essay, a successful convention would involve compromises. That is how agreements among discordant parties work. You hold your nose and accept things that you do not want for the practical reason that an unsatisfactory agreement is better than having your rights and duties established by accident and force.

This brings us back to the whistling November wind and the lawyering in the hold of the Mayflower. The acts done there multiplied in the New World. The making of civil bodies politic was repeated again and again in America, and that is the true heritage of which the Constitution is merely one example, however great and venerable an example it is. That tradition of consent and self-government includes a lot of high moments, from the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut to refusal to comply with Governor Andros’s revocation of the charters of the Dominion of New England leading to Andros’s arrest. It includes the Lee Resolution, the subsequent rationalization in the Declaration of Independence, and the particularization in the Articles and then the Constitution of 1787.

This is the sacred American heritage of consent. As it was for our separatist Pilgrims forefathers, it is, in a certain way, a religious calling. To neglect it, especially out of fear, is for lack of a better word un-American, and even impious, because it is, after all, a God-given right.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Leave a Reply