From the June 2012 issue of Chronicles.

Most retrospectives take the Swinging Sixties, and more particularly Swinging London, on their own terms. “Society was shaken to its foundations!” a 2011 BBC documentary on the subject shouted. “All the rules came off, all the brakes came off . . . the floodgates were unlocked. . . . A youthquake hit Britain,” and so on. For most young Britons, of whom I was one, what this mainly seems to have meant was some very silly shirts, marginally better food, and a slight increase in the use of soft drugs. By a lucky bit of timing, the introduction and rapid availability of the contraceptive pill coincided with the arrival of that other defining symbol of swinging bedroom etiquette, the duvet. Exact statistics are elusive, but as a result of these twin developments, it’s likely that a few more young women spent the night together with their boyfriends. But that was about it for the so-called youthquake. For millions of young Britons, it seems fair to say that sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll took their place against a normal existence of knitting, cricket, and worrying about O-level exams. A night out at The Sound of Music, followed by the Berni Inn Family Platter, remained the height of most teenagers’ aspirations. When Time came to dub London the “Style Capital of Europe,” it concentrated on a few photogenic locations and eye-catching developments such as miniskirts and the rise of the Rolling Stones. Despite the subsequent claims of the BBC, these were not events that appeared to be part of any broader revolution under way against the Britain of Hancock’s Half Hour, with its grinding conformity and identical red-brick semidetached houses furnished just like your grandmother’s.

Certainly, if you lived in Britain in the summer of 1968, a time of some domestic and international turmoil, the most commonly heard topic of conversation in many homes wasn’t the Vietnam War, or the rioting by French students, or the ending of British theater censorship and the subsequent arrival on the London stage of the “tribal love-rock” musical Hair. Nor was it the latest single by the Beatles or the Stones. The subject of most debate, among Britons of all ages, and at all levels of society, wasn’t even a figure generally associated with the Swinging Sixties. Rather, it was a 56-year-old man of rigid military gait, who happened to be a classical scholar, poet, author, and latterly Conservative Party Shadow Cabinet defense secretary, named Enoch Powell. It would be hard to think of a more profoundly divisive figure, not excluding Margaret Thatcher, at any time in postwar European history. In May of that year, dockers and meat porters left their jobs, and bus drivers abandoned their vehicles, to march on Westminster in support of Powell; thousands of other Britons paraded in the streets of London, Birmingham, and other cities, demanding his arrest; the BBC compared him with Hitler; ideologically pristine newspapers like the Guardian were taxed almost to the point of incoherence in their denunciations of him. The era would likely have been similar in tone and direction had Powell not lived; yet so bitter and prolonged was the debate he started, and so vividly did it reflect and illuminate its time, that it seems to assume ever greater significance—one of the key events that helped turn the 1960’s into The Sixties, and still sharply polarizing today, 14 years after Powell’s death.

What did Powell do? He got up one April Saturday afternoon at a meeting of his local Conservative Party and spoke about the issue of widespread immigration to Britain. Among other things, Powell recounted a conversation with one of his constituents, who had expressed the view that, “In this country, in 15 or 20 years’ time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.” Such remarks were not uncommon in the streets of Britain, as opposed to her legislative corridors, in the period leading up to the enactment of the Labour government’s Race Relations Act, which was to be debated in Parliament three days later. “Here is a decent, ordinary fellow-Englishman,” Powell told his audience,

who in broad daylight in my own town says to me, his Member of Parliament, that the country will not be worth living in for his children . . . I simply do not have the right to shrug my shoulders and think about something else. What he is saying, thousands and thousands and thousands are saying and thinking—not throughout Great Britain, perhaps, but in the areas that are already undergoing the total transformation to which there is no parallel in a thousand years of English history.

“We must be mad,” Powell continued, “literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.” He went on to make certain statistical forecasts about the exact nature, and likely consequences, of what politicians are now pleased to call the multicultural society. Of those journalists who urged the government to pass positive-discrimination laws, he argued, many were “of the same kidney and sometimes on the same newspapers which year after year in the 1930’s tried to blind this country to the rising peril which confronted it.” Then came the Sibylline climax of the speech with which Powell was forever to be associated. “As I look ahead,” he said,

I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood.” . . . Only resolute and urgent action will avert it even now. Whether there will be the public will to demand and obtain that action, I do not know. All I know is that to see, and not to speak, would be the great betrayal.

Powell was well aware of the furor his “Rivers of Blood” speech would cause, as disseminated, and often distorted, by the press. Indeed, he referred to it at the time, when coming to recount the story of his meeting with his constituent. “I can already hear the chorus of execration,” Powell noted, pausing to fix the local television crew with his basilisk stare. “How dare I say such a horrible thing? How dare I stir up trouble and inflame feelings by repeating such a conversation? . . . Because I have no right not to.” Although Powell was quite right in his prediction of the odium subsequently heaped upon him by the political establishment, he proved to be an only modestly gifted forecaster of future demographic trends as they applied specifically to the numbers of non-European migrants arriving annually in the United Kingdom. In the week following his speech, Powell told the Birmingham Post that he foresaw “as many as two million” such individuals settled in the U.K. by the end of the 20th century. He was rather too conservative. According to the 2001 Census, and in the terminology of Britain’s Office for National Statistics, the actual numbers were Indian, 1,053,411; Pakistani, 977,285; Mixed Race, 677,117; Black Caribbean, 565,876; Black African, 485,277; Bangladeshi, 283,063; Chinese, 247,403; Other Asian, 247,644; Other, 230,615; and Black (Others), 97,585—for a total of 4,865,276, or some 8.5 percent of the British population. There are many who believe, for a variety of reasons, that these figures significantly undercount the true totals. It seems probable that the number of immigrants as a whole has not fallen in the last 11 years.

Not only Labour ministers, but many of Powell’s Conservative opposition colleagues were outraged at the speech. Four members of the Shadow Cabinet publicly threatened to resign unless he was sacked, and even Margaret Thatcher, then a 42-year-old Shadow fuel spokesman, thought the speech was “strong meat.” Over the following days, the note of simulated or real moral horror was stoked by a series of inflammatory headlines in the broadsheet press. Even when Powell was duly axed by his party leader Edward Heath (in the last conversation they would have), there were those on both sides of the House of Commons who called for him to be charged with criminal incitement. In contrast, 1,400 London dockers marched on Downing Street in mass support of the speech. The organizer of the march, Harry Pearman, told the press, “I have met Enoch Powell and it made me feel proud to be an Englishman. He told me that he felt that if this matter was swept under the rug he would lift the rug, and do the same again. We are representatives of the working man. We are not racialists.” Powell himself insisted that he spoke from a position not of “ethnic superiority . . . indeed I feel that in many ways the Indian is a higher being to the European,” but from concern that unbridled immigration would fatally alter the “historical and social composition” of the country, to no one’s ultimate benefit. “I have, and always will, set my face like flint against making any difference between one citizen of this land and another on grounds of his origins,” he told the Times. A Gallup poll published on April 30, 1968, found that 74.7 percent of respondents agreed with what Powell had said in his speech; within the next week, he received 120,000 letters of support from what he called “ordinary English men and women of every stripe.”

Nor was Powell without his influential backers, even if, for the most part, they chose to express their solidarity away from the glare of public scrutiny. The left-wing firebrand and future Labour leader Michael Foot told a reporter he thought it “tragic” that this “outstanding personality” should have been widely misunderstood as “predicting actual bloodshed in Britain,” when in fact he had used the Aeneid quotation “merely to communicate his own sense of foreboding.” A more robust defense came from the rock star Eric Clapton, who, among other unappreciative remarks about “suntans,” asked a concert audience in Birmingham, “Do we have any foreigners here tonight? If so, please put up your hands. Any Wogs, I mean . . . Well, wherever you all are, I think you should all just leave. Not just leave the hall, leave our country. I think we should vote for Enoch Powell.” With the benefit of 30 years’ hindsight, Heath himself was to admit that some of his estranged colleague’s remarks both on the “economic burden of free movement” and the “dangers of an internationally untrammeled America” had been “not without prescience.” Margaret Thatcher told the newspaper Today in an interview shortly after her departure from office in 1991 that “Enoch [had] made a valid argument, if in sometimes regrettable terms.” Many in today’s Conservative Party have expressed it more vigorously than that, and in August 2011 the British constitutional historian David Starkey commented, “Powell’s prophecy was absolutely right in one sense. The Tiber didn’t foam with blood, but flames lambent.” Dr. Starkey went on to attribute the widespread rioting in London that month to the fact that too many young white people had “now become black”—an explosively provocative notion to the BBC and many other opinion-formers, but an incontrovertible truth to anyone who has walked alone in Britain’s city streets after dark on a Saturday night.

John Enoch Powell was born on June 16, 1912, the only child of an English provincial schoolteacher, and the grandson of a coal miner. He excelled in school, and at 17 went up to Cambridge University, where he achieved a rare double-starred first-class degree in Latin and Greek. Feeling this was an inadequate qualification for him to achieve his ambition of becoming viceroy of India, Powell enrolled in London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, where he not only swiftly mastered Hindi and Urdu but published a volume of poetry broadly in the school of his friend and mentor A.E. Housman. To read these transparently honest verses is to enter a world it is difficult nowadays to imagine. It is a world where patriotism, dedication to a cause, devotion to duty, and service to one’s fellows have not been tainted by irony or satire. Whether writing of colleagues at Cambridge or male friends in London, love is a word Powell uses without embarrassment, echoing in a less lyrical way the emotions that Housman invests in his wistful evocations of doomed young men. (It is perhaps redundant to add that several of Powell’s later critics have detected a homosexual element in his writings.) What fascinates about his career as a whole is its combination of the abstract intellectual and the hardheaded realist. In 1938, Powell resigned as professor of Greek at Sydney University, a position he had taken at the age of 25, after registering his disgust at Neville Chamberlain’s “terrible exhibition of dishonor, weakness and gullibility” in appeasing Hitler at Munich, and returned to England to enlist. On the four-week journey home he taught himself to speak Russian, since he thought “Russia would hold the key to our survival and victory, as it had in 1812 and 1916.” In September 1939, Powell was graduated at the top of his officer-training class. In the course of a picaresque war service, he became the youngest brigadier in the British Army, and was awarded the MBE for his intelligence work in helping to plan the Battle of El Alamein, among other services.

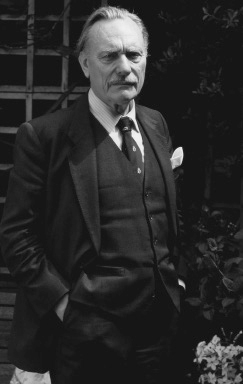

Powell’s subsequent political career equally abounded in paradoxes. He loved clubs, particularly the House of Commons and the Conservative Party, and wasn’t adverse to the exercise of personal power. Yet he refused office in 1952, resigned on a point of principle from Harold Macmillan’s Treasury team in 1958, and refused office again in 1959 and 1963. As a general rule, Powell was associated in these years with free-market economics, reductions in public spending, and an unflinching devotion to the monetarist theories of Milton Friedman. It might be said that he was preaching economic Thatcherism two decades in advance of Lady Thatcher. Well before April 1968, there was an otherworldly, if not prophetic, aspect to Powell’s public image that went far beyond the specifics of his policy statements. Apart from his deep, monotone voice and the association of the name Enoch itself, there was his splendidly anachronistic appearance, stern and thin-lipped and invariably clad in a funereal three-piece suit at a time when even many of his Conservative colleagues had abandoned themselves to polyester slacks and safari jackets. In photographs, Powell made no compromise with the camera, gazing unsmilingly into the lens or far into the distance as though the present were losing its interest for him.

Though Powell could endow even the driest of economic statistics with the gravity of a biblical portent of doom, in private he was very far from the mirthless haruspex of popular legend. “Mr. Heath is a methodical man,” Powell announced in 1969, speaking of his corpulent former boss. “I think he must once have missed an important lunch engagement, and it preys on his mind.” His glancing humor was not long subdued by Heath’s surprise accession as prime minister in June 1970. The two men were not reconciled. Powell’s refusal to support Britain’s membership in the European Community led him in the February 1974 election to urge his followers to abandon the “squatter in Downing Street” and vote Labour. He characterized the choice facing the British electorate in that contest as the “generally unappealing one between a man with a pipe and a man with a boat.” When he awoke to learn that Heath had narrowly lost the poll, he went to his morning bath singing the Te Deum.

I was at Cambridge later that year when Powell arrived one wet Sunday afternoon to visit his younger daughter, who was an undergraduate housed in the next-door college. Standing on wooden crates, explicitly phrased placards in their hands, a hundred or so members of the student union demonstrated their commitment to free speech by pelting their guest with eggs and other materiel. Powell walked calmly through the mob, supporting his wife by the arm, and shaking his head with a smile. When the family returned to their car a few minutes later, a full-scale riot was in progress. Supporters of Powell who had hurriedly arrived on the scene struck up the national anthem to drown out the catcalls of his opponents. As the car pulled out, police were breaking up the fighting between the two groups—a not unrepresentative British-campus scene of the mid-1970’s.

Powell returned to the House of Commons in October 1974 as the Ulster Unionist MP for the Northern Irish constituency of South Down, which he represented for the remainder of his career. This was not a man who conspicuously sought the quiet option in political life. For the next 13 years, Powell remained, depending on your point of view, a deeply moral Christian thinker and patriot with the courage to break from the postwar consensus or, as Edward Heath once put it, “an ambitious brute.” There followed a number of colorful parliamentary statements, policy initiatives, and more speeches. Following an IRA bombing outrage in Birmingham, Powell, almost alone among parliamentarians, opposed the Labour government’s hurried introduction of a Prevention of Terrorism Act, warning of passing legislation “in haste, and under the immediate pressure of indignation, which touches the fundamental liberties of the subject.” Powell was not immediately enthusiastic about Heath’s successor as Conservative Party leader, Margaret Thatcher, whose success he attributed to the fact that she faced “supremely unattractive opponents at the time.” He did, however, robustly defend Thatcher’s decision to send troops to repossess the Falkland Islands from their Argentine invaders, while coming to argue that Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent was no more than an “unaffordable farce,” and her foreign policy as a whole “deformed by our excessive deference to the United States.” Nor did Powell shy from returning to the race-relations debate. Following widespread street rioting in May 1981, he predicted a situation in which “inner London become[s] ungovernable, or [sees] violence which could only effectively be described as civil war”—an apt description of the outbreak of mass criminality on the capital’s streets 30 years later. Toward the end of his political career, Powell was engaged in campaigns as diverse as his insistence that Earl Mountbatten had been murdered not by the IRA but by the “American intelligence services and their friends,” and that fox-hunting was “a much-loved side of our national character,” and thus “deeply antipathetic to those in the Labour party.”

Powell retired from public life in 1987, but was characteristically blunt three years later when asked to comment on the buildup to the Gulf War. “The world is full of evil men engaged in doing evil things,” he told an interviewer.

That does not make us policemen to round them up, nor judges to find them guilty and to sentence them. What is so special about the ruler of Iraq that we suddenly discover that we are to be his jailers and his judge? . . . I sometimes wonder if, when we shed our power, we omitted to shed our arrogance.

Powell was no admirer of what he called the “little magic circle of ruling dictators,” whether they be in Baghdad, London, Washington, or Brussels. He consistently opposed the chimera of European political unity, because, much like unfettered immigration, “it destroys the essence of nationhood.” Speaking 20 years before the latest such crisis, he saw only “crippling dislocation” arising from a single European currency, another feat of prediction beyond most leaders at the time. Addressing a Conservative fringe conference in January 1990, Powell said,

We are taunted—by the French, by the Italians, by the Spaniards—for refusing to worship at the shrine of a common government superimposed upon them all . . . Where were the European unity merchants in 1940? I will tell you. They were either writhing under a hideous oppression or they were aiding and abetting that oppression. Lucky for Europe that Britain was alone in 1940.

For the most part, Powell was notably unsentimental about the art of politics. In retirement, he spurned the “contemptible directorships and sham fees” enjoyed by many of his colleagues, and declined to write his autobiography on the grounds that it would be “like a dog returning to its vomit.” As an alternative, Powell taught himself Hebrew (his 12th language), and spent much of his final years engaged in a close textual analysis of the Gospel of St. John.

Enoch Powell died on February 8, 1998, aged 85. There was a public funeral service at St. Margaret’s, Westminster, where he had been a churchwarden for 40 years. Even in those surroundings, his opponents were loudly represented. If you were to distill the essence of Powell’s professional life, it might be that the truly fearless independent operator, however trying the circumstances, can so effectively puncture the arrogance of the political elite. This may be harder to achieve even than rising to the leadership of your country. And it is just as splendid.

Leave a Reply