The amazing thing about the nuclear debate and the Catholic bishops’ participation in it is that the accumulated wisdom and experience of mankind, as well as the Church’s pronouncements on peace and war, are so completely ignored. This is quite a natural phenomenon on the part of so many lay debaters: it belongs also to mankind’s experience that in every age there are men who believe that theirs is a privileged moment of division in history: between a long but essentially unenlightened past and a bright and rational future in which mankind will embrace full happiness and harmony. The falsely wise man, whom I prefer to call a “Utopian” and whom Mgr. Knox used to call an “enthusiast,” believes that the times have somehow thickened during his own lifespan, and that history has undergone an ontological transformation. He himself—a Hegel, a Marx, a Nietzsche—stands on the threshold of a new era into which it is given to him exclusively to peer, prophet-like.

It follows from such premises that the Utopian regards events during his own lifetime as particularly dramatic, good or bad, but sufficiently so to start all men, or at least an elite, to think on different lines from the traditional course. Such a dramatic event, according to the false prophets, is today the military use of nuclear power, a gigantic misuse of human talents and abilities which will, however, introduce the redemption of history from the greatest plague of all, war.

War, the killing of men, is based not only on distrust, but also on the assumption that its destructiveness has always been limited by the imperfection of available weapons. Now, however, says the Utopian, war has become qualitatively different from what it used to be: global, devastating potentially the whole planet, murdering all men in one single apocalyptic blow. The whole matter must be rethought, antiwar movements must be started everywhere, hostility to nuclear wars, offensive or defensive, must be taught in schools, parades of little children must be used, along with propaganda posters, to soften the statesmen’s hearts. By the same relentless propaganda, all men must be made conscious that now is the time to end all wars, that there is not a day to lose. A Harvard Law School professor, one Roger Fisher, who crisscrosses the planet teaching the techniques of “conflict-solving” (if anything, by his primitive arguments he sows the seeds of new ones), suggested that the heads of State of the two superpowers should be compelled to kill an escort before pushing the button of the nuclear holocaust.

Now what is so strange in this whole thing is not the pseudo-prophets’ alarm over new hardware: there were those who saw a threat to civilization when the crossbow was invented, or gunpowder, the rapid-fire machine gun, or toxic gases. Of course, potentially damaging inventions should always be opposed—but not with apocalyptic arguments, not with a thesis that mankind’s fate is in the balance, that history may now turn from evil to goodness. Even reputable philosophers have succumbed to this false vision: Immanuel Kant drew up a project-blueprint for permanent peace. The strangeness and novelty inhere in the fact that we find bishops, entire episcopates, joining the false prophets and adopting their faulty reasoning—as if the Church’s teaching were not available in order to put matters in perspective, to fight evil but without the naive, ideological view that it can be uprooted by wishful thinking and an all-too-human manipulation.

An entire sociological study would be needed to explain why the American bishops have turned, roughly in one decade, from one conformity to another—from a naive belief in “old” America: the America of businessmen, hard hats, and “God’s own country,” to a ritualized hatred of the “new” America: home of intolerable poverty, racial exploitation, warmongering, and inequality. I think that the switch from one superficial view to another has as its basis the crusading spirit of all Americans, bishops or laymen, Christians or Jews. The nuclear bomb and the economic issues provide at present safe crusading causes, attention-catching slogans—and pastoral letters full of cliches.

A few years ago I wrote a book in which I warned that as the American Church increasingly distances itself from Rome, we might see bishops’ committees turning into a kind of shadow-cabinet to the government in Washington. Such a shadow-cabinet would have as many ministries as the government has, dealing with foreign policy and agriculture, military matters and labor—mostly by incompetent people whose true mission lies in spirituality, moral matters, and diocesan administration. Today, what had seemed to be an impossibly grotesque suggestion becomes reality, as the bishops issue letter upon letter about things alien to the ministry that Christ entrusted to them.

The other reason for the sudden irruption of utopianism into the bishops’ undisturbed universe may be located in the kind of ecclesiastical coup d’etat that took place when the new, progressive, and leftist seminarians began leaving their classrooms and occupying, now as ordained priests, the secretariats of episcopal commissions and conferences. While formerly, on matters where they lacked competence, the bishops used to consult people of varied backgrounds, they now have at their elbow reputedly bright young college graduates, with doctorates in sociology, psychology, and foreign policy. Documents issued bear the mark of brain trusters, with the result that “new research” and “scientific expertise” tend to replace “old doctrine.”

These and other reasons explain why the bishops, in a turnabout of one short decade, have lined up with the fashionable ideological opinion—at a time when the German and French episcopates, for example, took an altogether different stand on the war and peace issue, hi view of the possible confusion, it is thus important for us to restore the Church’s correct teaching on this matter. The American bishops and their advisors tend to overlook and often to simply ignore the Church’s teaching.

We can make short shrift of the general argument of all pacifists and quasi-pacifists that nuclear weapons represent such an absolute evil that, as a result of their availability, wars must be outlawed and all previous views about their possible justness scratched. If the Bomb is indeed so absolutely new in the annals of mankind, why would the communist regime, against which it is primarily aimed, also not be absolutely new and absolutely noxious? Never has there been, under Assyrian emperors or Nero, under Chinese despots or Caligula, such inhuman regimes as those which now cover one third of the planet and are still expanding; they represent a veritable “first” in their relentless efforts to change man by crushing his soul and destroying previous communities and institutions. The game of the “absolutely new,” requiring a total rethinking of history, doctrine, wisdom and experience, may be played by both sides; it leads only into a speculative impasse.

Let us abandon the impasse about what constitutes ontological change and try instead to restore Catholic doctrine on the matter of peace and war, a matter which also naturally includes all considerations about nuclear war. The latter requires no “new morality,” “new Christian vision,” nor any rewriting of doctrine. Instead, let us ask why the Church’s teaching on “just war” is under attack, an attack for which the nuclear issue may have merely contributed a pretext.

In modern thinking—which goes back to the 14th century and William of Ockham—the individual has acquired a disproportionate importance as the only verifiable reality. Communities, institutions, family, moral and juridical persons, and finally the social network have paid for this distortion. By the 18th century, it was denied that man needed the State to prosper, and it was proposed that Society is the product of a contract based on the hypothetical contractants’ “cupidity and fear of each other” (Hobbes)—in other words, on aggression and counteraggression. The ideal was the isolated “noble savage” and Rousseau’s similarly isolated Emile. A number of extremely fashionable ideas today, from Freudianism to existentialism, perpetuate the notion that society is man’s enemy and that our “pulsions” are all expressions of a fundamental hostility.

Under the circumstances, further confused by the neoliberal concept of the “minimal State,” we tend to locate the evil not in ourselves, but in the State as a concentration of power and evil interests. We have conveniently forgotten the old doctrine that the State too is God’s creation, a secondary cause without which man could not survive, though our memory can be restored when it suits our purpose: after their pastoral on nuclear war, the bishops—with supreme illogic—call upon the State to provide for the citizens’ welfare. It is absurd to give the State all the economic power—then deprive it of its primary function, the community’s defense.

If he is without any social and sentimental responsibility to family, group, community, or nation, the individual, by now a sheer abstraction, indeed has the right to adopt a “pacifist” attitude, as far as his own person is concerned. He may decide not to resist attackers, thiefs, murderers. Suppose, however, that the same individual is father of a family, a watchman on medieval city walls expected to alert fellow-citizens to approaching marauders, or the president of a modern republic. His duties in these functions neutralize and overcome his individual inclinations and command him to respond to the aggressions in kind. It would be unspeakably immoral of him not to resist, not to protect the group he leads. It would not be a question of neutrality or pacifism. In fact, the pacifist leader would be guilty of taking the attacker’s side against his own people.

This, in essence, is the core of the Church’s position on the “just war,” now being occulted by ideological and emotional verbiage. This position is so crystal clear and correct that appeals to the “absolutely new nature” of atomic weapons have no logical power against it. No matter what risks are taken by the self-protecting group—a nation, as the case is—the natural right, even duty, of self-protection prevails over all other considerations. The opposite position is that the nuclear weapon has changed the nature of war, whether offensive or defensive. The assertion that nuclear weaponry is not “hostile to any kind of aggression”—a cheap slogan—is also aimed at the dismantling of the State, whose primary justification is, precisely, external defense.

The American bishops offer several alternatives: nonresistance to the attacker combined with noncooperation with him, now the occupier of the national territory. This sounds like a child’s vagaries in the world of adults, for the occupier they and we have in mind has means to compel “cooperation” in chains and gulags. Nor would the enemy have even a minimum of grudging respect, as it had for Hungarians who had risen up, arms in hand, in sacrifice for their nation. The American bishops not only oppose reason and dignity, they recommend cowardice as a view of the new historical epoch. Or, worse, they seek to formulate impossible—and immoral—amalgams, as Cardinal Bernardin’s ingenious proposition that “life-issues”—abortion, war, capital punishment—should be treated as one “package.” Since wars are not likely to go out of fashion this side of Christ’s Second Coming, Bernardin’s message is to keep abortions forever on the book.

In sum, the United States bishops line up on the side of pacifism, which is itself a militant, aggressive, quasimilitary operation. The “pacifist” label has nothing to do with it; it is not the first time in this century that a reassuring label covers an evil merchandise. The peace that the Church preaches is a conversion of the heart. Before that can happen, the human condition imposes its servitudes. History, in fact, has never known a peace based on agreement and final reconciliation, only such a peace that was in the victor’s interest, although the defeated also gained some satisfaction. There was the pax Romana, the Spanish peace in South America, the “peaceful” century in Europe, from 1815 to 1914, paid for by colonial people, and then the post-1945 “peace,” as bloody and violent through its local wars as any major conflict ever. The bishops, engaging in political rhetoric instead of moral exhortation, have turned into peace-activists; yet they speak in a moral vacuum.

The world, for all its imperfections, is at least more concrete than the bishops’ untutored imaginings. Basically, wars are not mere clashes of arms. They are ideological conflicts between sets of definitions. The victor imposes not only his material conditions, but also, more importantly, his monopoly of meanings. Hitler and Chamberlain obviously defined “peace” differently, and the question in 1939 was whose definition would prevail. We are instructed by the various pacifist schools of thought that “peace is in mankind’s rational interest”; but even if we grant that the rational prevails over the irrational, who defines “rational” or “interest”? Thus what appears to A as rational, is interpreted by B as cowardly, an invitation to aggression.

While the Church teaches the conversion of hearts, a process to end with history itself (and even then incompletely, since there will remain the redeemed and the damned), the pacifists—and the American bishops—insist that this be done here and now, with the help of technological dismantling of existing arsenals. Even if this were a possibility, where is the assurance that tomorrow the blackness of the warring heart does not again prevail—and the military technology reactivated? Place all weapons at the disposal of the United Nations? But this organization too is human, and the only difference would be that wars would henceforth be called “insurrections against a World-State” that would be by definition, but only by definition, peaceful.

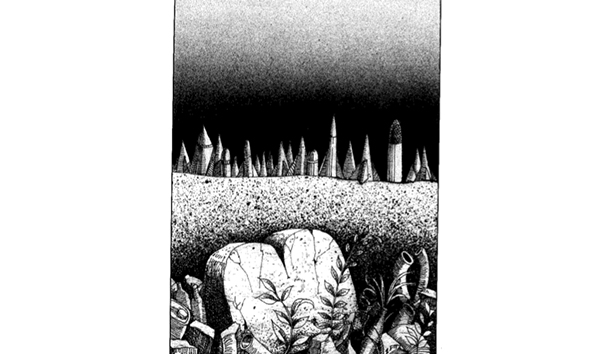

The most that can be hoped for is what is promised in the permanent teaching of the Church: temporary and limited peace periods, guaranteed by the self-interest of sovereign States. This perspective is unacceptably modest for the enthusiasts, both within and without the Church, who forget that in feudal times the Church, depositor of meanings, could impose the treuga Dei, a temporary and limited peace, not more. At the time, the “balance of terror” existed between the armor of knights, a kind of mutual deterrence. Yet, no permanent peace resulted, mankind survived and went on devising new weapons: better siege machines, more combat-ready standing armies, tanks, bomber planes . . . the Bomb. Not a lovely enumeration, but apparently within the scope of man under God’s providence.

Leave a Reply