For Texas conservatives, a surprisingly strong showing by Democrats in their deep-red state in November’s midterm election was an unexpected wake-up call. The results also set me to thinking about my own personal history with the Lone Star State. And how, in the absence of vigilance, the long, proud heritage of a particular place can so easily be put at risk.

To a kid growing up in the soft, sun-kissed climes of Southern California in the 1950’s and 60’s, the family’s annual two-week trek to visit relatives in the Texas Panhandle was an exotic and welcome respite. There was nothing soft about the High Plains of the Panhandle. The northernmost part of the state was farming and ranching and oil and gas country, and its residents—my grandparents and uncles and aunts and cousins—were independent, realistic, willful people who worked hard and knew the difference between right and wrong. They listened to Paul Harvey’s midday radio broadcast and attended church on Wednesday nights and twice on Sundays.

My late uncle W.C. Crawford, “Dub” for short, exemplified the breed. Known as the Odessa Kid during his days as a cowhand, he went on to help start up natural-gas plants for Roy Huffington, a legendary Houston wildcatter. Dub told me how his father, a farmer who was born in Williamson County, Texas, in 1878, had instilled self-confidence in him at an early age: “I remember he sent me to do something when I was four or five, maybe, and I came back and said, ‘Dad, I can’t do that.’ He set me down and said, ‘Son, I’m never going to tell you to do anything you can’t do. Some of the jobs are going to be difficult, but if you try long and hard enough, you can do it.’ He taught me I could do whatever needed to be done.”

Once, after he’d relocated from Texas to California’s Central Valley, Dub volunteered to drive my nine-year-old daughter, Sachiko, to the airport in Los Angeles, where she would catch a plane back to our home in New Mexico after visiting my mother in San Diego County. The flight was canceled, though, so when ticket holders queued up to book the next one, which turned out to be oversold, they began clamoring, some louder and more rudely than others, for a coveted seat. Finally, Dub and Sachiko reached the front of the chaotic line. “This child must get on this plane to go home,” Dub said to the ticket agent softly, but with rock-hard resolve. “There is no other choice.” Not only did Sachi get her ticket, but they bumped her from coach to first class.

Texans like Dub were a big reason I was happy to move to the state in the 1990’s, after years spent living in New Mexico and California. My native California, it seemed to me, had in recent years become a lost cause, with leftists and bureaucrats ruling the roost, enabling all manner of uncivilized behavior. In San Francisco, for example, homeless people routinely would break into my (then-grown) daughter’s parked car and sleep in it overnight. With housing, energy, and other costs sky-high, there was no shortage of homeless and other struggling people around. For that you could thank the state’s one-party rule by Democrats, who blessed the state with exorbitant taxes, environmental extremism, sanctuary cities, powerful unions, and arbitrary overregulation. Of course, California’s wealthier residents—the tech entrepreneurs, urban hipoisie, and limousine liberals of all stripes—did just fine.

Texas, by contrast, was ruby red, in keeping with its historic character. Although the state didn’t begin voting Republican in earnest until 1978, when Bill Clements was elected its first Republican governor, the Democrats who’d dominated the place for more than a century were more boll weevil than left-wing. Sam Gwynne, a former executive editor of Texas Monthly magazine, noted in a 2005 interview for PBS’s Frontline series that small government and low taxes were “always true” in Texas, which until the late 1970’s had been “Democratic, but fundamentally conservative.”

That approach led to spectacular economic success for the state. With its low taxes, minimal regulatory barriers, and reasonable cost of living, including relatively affordable housing, Texas became a magnet for jobs, companies, and people. During the 12-month period ending in October 2018, the state enjoyed the fastest employment-growth rate of any large state. Chief Executive magazine named it the country’s No. 1 state for business for the 14th straight year. And tens of thousands of people continue moving to Texas each month, with California in recent years sending more than any other state.

Today, though, many are wondering, and worrying, how long Texas will be able to maintain the conservative values and governance that spawned this success. If it fails to do so, they fear, it will no longer be a reliably red bulwark against blue states like California and New York in presidential elections. The recent November 6 midterm results, when Democrats stunned the GOP in Texas by racking up more wins and near-misses than they had in decades, were a cause for concern—and not just for Texans. As Kevin Roberts, executive director of the right-leaning Texas Public Policy Foundation, says, “As Texas goes, so goes America.”

Although Republicans still hold every statewide office in Texas—just as they have since 1994—they received a major scare in the 2018 race for U.S. Senate, when Democrat Robert Francis “Beto” O’Rourke lost to Republican Ted Cruz by about 220,000 votes out of 8.3 million cast, or just 2.6 percentage points. In 2012, by contrast, Cruz rode high on Tea Party sentiment to defeat a little-known opponent by 16 percent, or 1.25 million votes. Even the state’s popular governor, Greg Abbott, beat a very weak Democrat this year by just 14 percentage points, down from his 20 percent margin of victory against state Sen. Wendy Davis four years earlier. In other 2018 races, Democrats did more than just scare the GOP. They flipped two congressional seats in the Houston and Dallas areas—the latter had been held for 22 years by Rep. Pete Sessions, chairman of the House Rules Committee—and made notable gains in the Texas House and Senate. The Dems picked up two seats in the state’s upper chamber, bringing the split there to 19-12 in favor of Republicans, and no fewer than a dozen in the House, cutting the GOP advantage to 83-67.

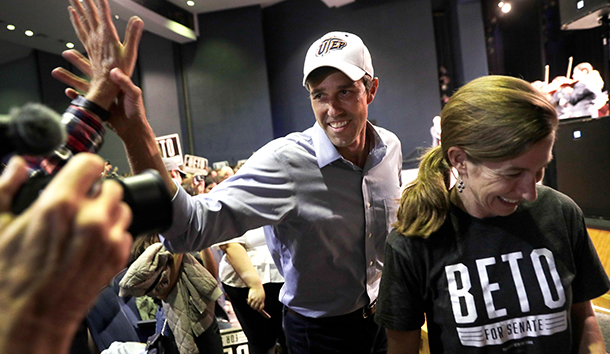

There were several reasons for these eye-opening results. These include a much higher turnout, with 53 percent of Texas voters participating in the 2018 election, up from 28.3 percent in 2014. The state’s shifting demographics also came into play, with the biggest urban metros—Houston, San Antonio, Dallas, Austin, and Fort Worth, in that order—increasingly dominated by younger, more liberal, and more minority voters. Distaste for President Trump, especially among Hispanics and suburbanites, including college-educated white women, played a role as well. Nothing, though, explains the Democratic gains more than the lightning-in-a-bottle Senate campaign of O’Rourke, a three-term, 46-year-old congressman from El Paso, in the western corner of the state. O’Rourke created such buzz in the Texas and national media that he lifted Texas Democrats to victory up and down the ballot, largely because many of the state’s residents opted for straight-ticket voting. (Texas has been one of only eight states allowing straight-party voting, but last year Governor Abbott signed a bill to eliminate the option starting in 2020.)

Tall (6’4″), slim, and energetic—invariably described as “Kennedyesque”—O’Rourke effused charisma, especially to Millennials and other true-believing members of his party. In contrast to the somewhat robotic, telegenically challenged Cruz, whose popularity took a hit following his failed run for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination, O’Rourke had a youthful, freewheeling image. He made a point of visiting all 254 Texas counties during his 19-month-long campaign, generating momentum—and plenty of adoring press—for his upbeat, post-partisan stump speeches. “We are not running against anything or any political party,” he claimed.

He also boasted about shunning consultants and pollsters and PAC money, relying largely on social media to spread his message. A former 1990’s era punk-rock musician, O’Rourke posted relentlessly on the likes of Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. One widely seen video showed him riding a skateboard through the parking lot at Whataburger, a popular Texas hamburger chain. Another eavesdropped on O’Rourke sitting in his car in a fast-food line, “air-drumming” to The Who’s “Baba O’Riley.” When Texas music icon Willie Nelson played a concert supporting O’Rourke in Austin, nearly 60,000 people showed up, and Beto took the stage to help Willie sing “On the Road Again,” of course. Even O’Rourke’s ubiquitous, black-and-white yard signs were cutting-edge; nothing so mundane as red, white, and blue for Beto.

Despite the record amount of money ($80 million) and enthusiasm O’Rourke generated among Democrats around the country, some Texans were rightfully skeptical. For example, a Caucasian with Irish roots who goes by the name Beto (a Spanish nickname for Robert) must be “Hispandering,” critics charged. O’Rourke countered that Beto is simply what he was called growing up in El Paso, where the population is overwhelmingly Hispanic. But according to PolitiFact Texas, a March 2018 profile of O’Rourke in the Dallas Morning News told a different story: The congressman’s late father, Pat O’Rourke, who was an El Paso County commissioner and judge,

once explained why he nicknamed his son Beto: Nicknames are common in Mexico and along the border, and if he ever ran for office in El Paso, the odds of being elected in this mostly Mexican-American city were far greater with a name like Beto than Robert Francis O’Rourke. It was also a way to distinguish him from his maternal grandfather, Robert Williams.

When O’Rourke was told about his father’s explanation, the congressman said, “I believe it, I believe it. He was farsighted in that way.”

Many Texans also saw a cynical disconnect between O’Rourke’s high-minded platitudes on the stump and his actual politics. While claiming to be “running to represent everyone,” regardless of geography or party affiliation, O’Rourke’s beliefs were light-years to the left of the state’s mainstream. He not only rejected the President’s plan for border security—“We don’t need a wall,” he told late-night TV host Stephen Colbert—but also said he was open to abolishing the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. He argued for a Bernie Sanders-like single-payer health-care plan, and voted against the $1.5 trillion tax-cut bill. He favored President Barack Obama’s Iran deal, bragged about getting an “F” rating from the NRA, and opposed a bill to outlaw abortions after 20 weeks. When O’Rourke doubled down on impeaching Trump during an October appearance on CNN, it seemed as if he might finally have gone too far. Even Joe Biden said, “I don’t think there’s a basis for doing that right now.”

Thankfully, most of geographic Texas voted with its eyes wide open. According to an analysis by the Texas Tribune, the state’s 172 “non-metro” counties pushed Cruz over the top, with the incumbent winning the rural counties by a margin of 73 to 26.6 percent for O’Rourke. That result, combined with Cruz’s 59-41 percent edge in the mostly suburban and exurban counties, helped overcome—but just barely—O’Rourke’s advantage in the state’s six biggest metro counties, where he swamped Cruz by 61.8 to 38 percent, or nearly one million votes.

The next few years will show whether the gains Texas Democrats made in November are sustainable, or were merely a Beto-driven blip. Despite his loss, O’Rourke already is being touted as a leading candidate for his party’s 2020 presidential nomination, and he says he’s considering such a run. He’s also being talked up as a potential challenger in 2020 to Republican John Cornyn, Texas’s senior U.S. senator. But Cornyn is a more moderate and less polarizing figure than Cruz. And O’Rourke, who spoke approvingly of Cornyn during the 2018 campaign, has thus far shown no inclination to take him on.

More troubling for Texas Republicans are the inroads Democrats made this past election in Congress and the state legislature, especially in the state’s big-city and suburban Republican counties. With straight-ticket voting gone, the GOP may feel slightly more sanguine about its prospects two years from now. But that could be a mistake. Those who contend Republican losses in 2018 were “just the Beto effect are kidding themselves,” says state Rep. Morgan Meyer, a GOP incumbent who narrowly beat a little-known, first-time candidate in deep-blue Dallas County: “This is something we Republicans need to take seriously. We’re going to have to work across the aisle more and focus on issues that are important to people.”

Two issues that Meyer and others identify as top priorities are property-tax relief and school finance reform. Local property owners have been paying for a bigger and bigger share of public-education spending in Texas, leading to complaints about the burdensome system as well as subpar education results. Members of both parties have said these intertwined concerns would lead their agendas on January 8, when the state legislature began meeting for its 86th biennial session in Austin.

Tom Pauken, a former chairman of the Texas Republican Party who served on President Ronald Reagan’s White House staff, shares Meyer’s sentiment. Pauken says if Republicans hope to remain the majority party in Texas, they’ll have to “put together a broad coalition” and actually fix problems like the school-finance conundrum. As it is, “there’s too much sizzle and not enough substance,” Pauken said before the November election. “Reagan ran to do something; too many are running to be something.”

If Republicans can help craft common-sense solutions, such as requiring voter approval for certain property-tax increases, and implementing a student-centered funding structure for public schools, their reputation as problem-solvers deserving re-election will be greatly enhanced. At the same time, the Texas GOP should double down on its educational outreach to Millennials, minorities, and newcomers, patiently demonstrating to them how, and why, the state’s success has been the result of anything but California-style big government. It might also try to persuade them that old-time, native Texans like Dub Crawford could teach them a lot about things like grit, resourcefulness, and perseverance.

Newcomers “just need to use a little cowboy logic when they get here,” Sid Miller, the Texas Agricultural Commissioner, told me recently. “We’re great because we’re independent. We’re not a litigious state, we’re a low-tax and low-regulation state, and that’s why we normally lead the nation in job creation and business startups. There’s a saying, ‘Don’t California my Texas.’ It’d be a huge mistake if they tried to change Texas values to New York or California values.”

Even after working for a decade at a city magazine in Dallas—where the trendy young editors believe that traditionalists are troglodytes and transgender politicians are cool because, well, they’re transgender—I’m personally hopeful that Texans will heed warnings like Miller’s. But I’m not ready to bet the farm on it yet.

Leave a Reply