“Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book rewritten, every

picture has been repainted, every statue and street building has been renamed,

every date has been altered. And the

process is continuing day by day and minute by minute. History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present in which the Party is always right.”

—George Orwell,

Nineteen Eighty-four

“America has only three cities: New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. Everywhere else is Cleveland.”

—Tennessee Williams

Cleveland is a wonderful city. My first “real” job was downtown at East 9th and Superior. The city is a metropolis of ethnic neighborhoods and displays a delightful cultural quirkiness. But the point Tennessee Williams had in mind is that some cities, by virtue of their history and culture, are utterly unique. New Orleans fits that bill.

The Big Easy will celebrate its tricentennial next year, having existed under French, Spanish, and British rule, as well as a brief period of independence, government under the Confederate States of America, and of course its affiliation within the United States. New Orleans is proof that flags and rulers and countries can rise and fall, yet cities and cultures and people remain. Its complex and interesting history oozes from the city’s pictures, statues, buildings, and other landmarks.

New Orleans is also known for its openness—for its respect of diversity and tolerance in the true meaning of those words. This is especially true regarding ethnicity. The city was not a melting pot or a salad bowl, but rather a bold, motley gumbo of French, Spanish, black, Creole, German, American Indian, and Southern cultures, with more recent seasonings of Vietnamese and Central American—all of them living and working side by side. And after Hurricane Katrina, our cultures were bound together through common suffering and striving and overcoming, intersecting with music, cuisine, local dialect, and endless festivals.

In the blink of an eye, this gumbo was spoiled. Our easygoing racial and ethnic concord has been shattered by a social-justice warrior, Mayor Mitch Landrieu.

At his behest and with the nod of the city council, four commemorative monuments, each over 100 years old, were removed by masked men. Three of their targets were world-class sculptures. Each had been erected after years of private fundraising, which sought donations not only in honor of Confederate statesmen and American heroes, but also in tribute to the thousands of soldiers who served Louisiana during its Confederate period.

On April 24, in the darkness of early morning, with snipers keeping watch from a nearby parking garage, the Liberty Place Monument was dismantled by masked firefighters who lacked training in historical preservation. Thus, it was not a surprise that the men damaged the obelisk during their bungling operation. The Liberty Place Monument was described as a “monument to white supremacy”—a gross oversimplification and misrepresentation of a significant historical event that took place during Reconstruction.

Following the first removal, the city announced that it would move quickly to dismantle the Jefferson Davis, P.G.T. Beau regard, and Robert E. Lee monuments. Mayor Landrieu wasted no time, as a proposed state bill drafted to protect such monuments remained tied up in an unfriendly committee in Baton Rouge. Activists from the Marxist-led Take ’Em Down NOLA (TEDN) celebrated the mayor’s plan to proceed; the majority of citizens, who did not want these monuments removed, could do nothing to stop it.

A 63-year-old black lady, Arlene Barnum, came from Oklahoma to start a candlelight vigil at the Davis Monument. An Army veteran, Arlene is seldom seen without her Confederate Battle Flag; she was taught by her grandmother to revere it in honor of her ancestors who fought for the Confederacy. Two years ago in Mississippi, Arlene left a Confederate flag rally with fellow black Confederate supporter Anthony Hervey. Their car was run off the road by militant activists. The vehicle flipped. Anthony died, and Arlene suffered a broken foot. Arlene remains undeterred.

Others began to join Miss Arlene at the Davis Monument.

Andrew Duncomb, also known as “the black rebel,” likewise made the trek from Oklahoma. Tall, clad in a black cowboy hat and his black Sons of Confederate Veterans “Mechanized Cavalry” vest, he cuts an imposing figure. Locals began to join the pilgrims with flags and candles of their own, and the little crowd began to grow.

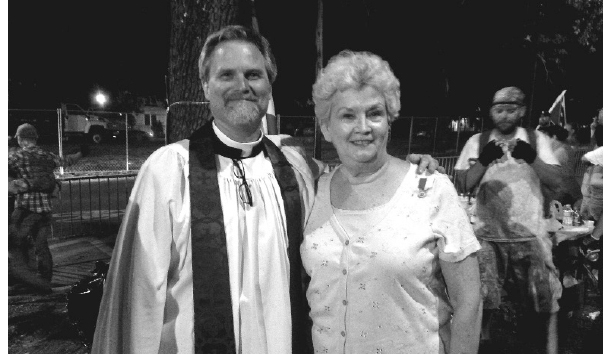

I am pastor of Salem Lutheran Church in nearby Gretna, Jefferson Parish. On April 28, I came to visit the monument supporters and was struck by the diversity of the crowd: locals and nonlocals; blacks, whites, Asians; well-dressed older ladies and young men in biker attire. Many were talking history, others conversing about politics. Their banners were also a variegated lot, including various Confederate, U.S., Gadsden (“Don’t Tread On Me”), and Louisiana flags. Many people were open-carrying firearms. Also, many in the crowd were live-streaming their vigil and conversations to Facebook. Drivers displayed a fairly even show of support (thumbs up, honks) and disdain (profanity, rude gestures). And aside from the occasional mouthy drunken college student staggering over from the corner bar to cry “racism” repeatedly, there were few confrontations.

However, peace was broken when TEDN and its allies in Antifa (the violent neocommunist organization that led riots in Berkeley) scheduled a May Day “barbecue” at the monument. Several hundred of these activists were bussed to the site. They pressed in on the monument defenders from all directions, causing the defenders to scale the monument for safety. Bottles were hurled. A woman was sliced in the leg by a man wielding a razor. Though the monument defenders were armed, they showed restraint. Meanwhile, police did nothing during this escalation. Monument defenders were told by insiders that the police were ordered to stand down. Facebook footage shows people calling for help from the police, only to have squad-car windows rolled up in their faces.

Seeing this on Facebook, I rushed to the scene. I got there just as police had finally moved in and cleared out everyone from the site, erecting barricades. I spoke to groups of monument defenders who told me what had just transpired—many had recorded the events on video. A lady in a wheelchair had had mace sprayed in her face. (Her attacker has been identified.) I ministered to an old war veteran who was suffering a PTSD attack because protestors threw a burning U.S. flag in his face and tried to hit him with a beer bottle. I asked an officer if it were true that they had been ordered to stand down. He did not deny it. (At a later monument event, an officer spoke to me privately, asking rhetorically, “Do you think I like just standing here?”)

Speculation ran wild about the monument being taken down that night, but nothing happened.

Crowds came the next day, as TEDN protestors and monument defenders both had swelling numbers, and a large number of police were on hand. The situation was tense, and monument defenders were frustrated. I decided to come and pray. I brought my hymnal and Bible, and was received warmly by the monument defenders. Respectfully, they gathered together and knelt, right on the street corner, in full view of the police and the mocking opposition. It was an extraordinary thing to behold. By this time, many of the monument defenders were wearing body armor and carrying pistols and military rifles. I led a service of Vespers. We prayed Psalm 91, a Psalm of protection from evil. I read John 16, the passage of hope where our Lord teaches that in Him, our sorrow will be turned to joy. I prayed for peace, for divine protection, for cooler heads to prevail, for the preservation of our history. I didn’t realize that the service was videotaped. People all over the country have written to me and were so happy to see prayer going on at such a time of unrest and anxiety.

I was able to give pastoral care to numerous people in private, off camera, and to encourage them to remain in the faith and to seek the Lord’s protection. Crowds from both sides continued to grow over the next few days. I interviewed an older man in distress whose impoverished great-grandmother had set aside small amounts of money to pay for these monuments—a mission of great importance to the ladies of the United Daughters of the Confederacy as the aged veterans were dying.

On the night of May 10, the two factions were corralled behind barricades in close range of each other as the bumbling masked firemen emerged from unmarked vehicles with obscured license plates to tear down the Davis Monument.

TEDN and Antifa activists hurled racial epithets toward the black defenders of the monuments. They chanted vulgarities, profanities, and blasphemies. Some of the monument defenders engaged them. Most stood somberly facing the monument, as flags were lowered in salute to President Jefferson Davis. The monument defenders sang “Dixie.” I watched one young man, amid the chaos and curses, standing at attention and rendering a military salute for well more than an hour, as the inept city workers struggled with the statue—which resisted them with a vigor that called to mind its real-life counterpart, who fought against being placed in leg irons in his postwar cell at Fortress Monroe. Once the statue was removed, monument supporters filed out. They were prevented from going directly to their cars and were forced to make a circuitous route through the streets of an already unsafe city.

The masked city workers returned to remove the pedestal some time the next day, leaving a bare slab on a site that had been adorned since 1911. To this day, no mention has been made of the whereabouts and contents of the time capsule that contained documents and Confederate and U.S. money that had been placed under the statue more than a century ago.

To the dismay of the gloating college students from the bar across the street, the slab has become a site for monument supporters to meet, fly flags, and play music. I met the great-great-granddaughter of Jefferson Davis there. Far from the promised racial utopia and city-wide unity promised by the mayor, the social fabric of the city now resembles the dilapidated ruins of the beautiful art that once stood at that location.

The next monument slated for removal was the beautiful equestrian statue of P.G.T. Beauregard at City Park. A masterpiece by world-famous sculptor Alexander Doyle, it was erected in 1915 after 22 years of fundraising, largely by widows and aging veterans. I had offered the Invocation at its 2015 rededication ceremony, 100 years to the very minute after the Invocation at its original dedication.

“Gus” Beauregard was a hometown hero, a mixed-race Creole whose second language was English. He served briefly as superintendent of West Point, and after secession and confederation served for a time as a popular general-in-chief of the C.S.A. After the war, he was an advocate of sectional reconciliation and black civil rights, proposing school integration in the 1870’s. His engineering exploits include inventing the street car, a line of which terminates at the ruins of his monument.

Although the Monumental Task Committee had documentation demonstrating that the city of New Orleans did not own the monument, and despite a city attorney’s recommendation of a 30-day stay to confirm that documentation, Mayor Landrieu refused to delay his plans. Civil District Court Judge Kern Reese denied a temporary restraining order, and simply declared that the statue belonged to the city.

Monument defenders began to gather around Beauregard, many carrying flags. Some kept all-night vigils. On May 14, the day before the rumored removal, two sisters, descendants of Beauregard, brought their nine-year-old daughter/niece to see the imposing statue one more time. The smiling little girl stood next to my 12-year-old son as a car pulled up. A passenger pulled out a gun and fired. Fortunately, the gun was firing paintballs. The girl was wounded in the chest and arm as the driver sped away. A Good Samaritan followed and notified the police. The four young men were caught with paintball equipment, arrested, and charged. That day, police were professional and helpful.

On May 16, the entire area was cordoned off. Crowds of protestors and defenders arrived and were somewhat separated by barricades. Monument protestors—vulgar and menacing—routinely crossed the barricade. My wife and son were present, as were people of diverse ages and ethnic backgrounds, to support the monument and to witness its historic dismantling. The monument opponents became more militant and aggressive, as once more the police made no effort to separate the groups or to deter violence.

Some of us had an interesting discussion with a recent college graduate, a young lady, who seemed baffled as to why a clergyman would be with the monument defenders. To her, it was inconceivable that there could be two sides to this issue, that anyone who was not a “racist” and a “white supremacist” would defend the monuments.

She wanted to know what my church and I were doing about racism. I told her that what I do is love my parishioners of every race and ethnicity as if they were my own family. I told her that I am with them on their deathbeds and in times of crisis. I give them the Body and Blood of Christ. I told her that what the Church does is raise the dead. She looked a little confused and repeated, “So, you raise the dead?” I reiterated that this is what the church does.

Though she was white, she was completely immersed in an Afrocentric and socialist reading of American history, one of “exploitation” and “white supremacy.” She had never read a book, an article, or even a Wikipedia entry regarding any of the men memorialized by these monuments, which she hated. Her solution to this manufactured conflict was that all monuments to white people be removed—that all place names, street names, school names, and tributes of any kind to white Founding Fathers—including Washington, D.C.—be removed or changed. She suggested that the U.S. flag should also be changed. I asked her about her own whiteness, and how her “privilege” should be addressed, and she was literally left speechless.

As the evening wore on, I led a service of prayer.

As it began, angry protestors immediately swarmed around us to hurl blasphemies and vulgarities. They pressed in on us and pushed us to the barricades. Men in bulletproof vests formed a wall in front of me. I let them know that I was OK, and joined them on the front line. I wanted to look at the protestors and to pray for them as well. It sent them into a rage. I made the Sign of the Cross over them individually and blessed them. Their response was to curse and to question whether I was actually ordained. They wanted to know where my church was and what seminary I graduated from. An oddly attired young man wanted me to interpret a passage for him. He was carrying on a strange monologue. I ignored their questions and continued praying Psalm 91.

A brass band appeared, and our attackers decided to leave. We later learned that Malcolm Suber, the communist “community organizer” and head of TEDN, was present with the band. Someone said that the Black Panthers had also arrived. At this point, the police finally stormed through the barricades to provide protection.

As the masked firefighters were trying and failing to pull down the statue, my family and I decided to go home. A bodyguard escorted us through hostile territory to the car.

The next day, we saw the destruction: The statue had been removed, and the beautiful pedestal had been torn up. The exquisite panel that included the general’s name was ripped off, exposing naked bricks. It gave the appearance of our South Louisiana above-ground tombs. Once again, the time capsule that had been placed within the statue has not been mentioned by anyone in authority.

It was later learned that this magnificent and priceless century-old masterpiece was lying in a city junkyard. A photographer brought members of the press and went inside without permission; the gate was left wide open. Pictures were televised of the Beauregard statue and dismembered pieces of its pedestal resting among rusted car parts and derelict tires.

The last remaining monument was the most challenging: a 16-foot, 7,000 pound colossus of Robert E. Lee (also an Alexander Doyle piece) atop a 60-foot stone column surrounded by streetcar wires. When the area was cordoned off, it became apparent that Lee’s removal was imminent. Monument defenders were corralled into a barricaded area at the base of the monument. Monument protesters poured in, again cursing and screaming vulgarities. A man who claimed to be “God” and “Allah” called for Muhammad Ali to replace Robert E. Lee. A brass band showed up. A nearly naked dancer with a blue Afro gyrated and twerked as “Allah” joined in. An older lady seemed to be performing a voodoo ritual. Against this spectacle, I prayed the Psalms loudly. I was singled out for abuse and accused of raping boys. Others demanded to know where my church was—as if I would tell them!

During this standoff, the acrid aroma of drugs filled the air. “Allah” scaled the monument and was arrested. An altercation happened, and mace was sprayed. The police came and separated the sides. It was announced that the planned removal was being delayed because of high winds. A protestor stole a flag from one of the defenders. She was waving it around like a trophy and got into her car. Monument defenders surrounded her car and refused to let her leave. The police forced her to return the flag. A monument defender was struck in the head by a man wielding a drumstick.

The next day, the Lee statue was removed, 133 years after it was installed amid thousands of people, including Union and Confederate veterans, who came to honor the veterans and leaders of the South in the reunited country. The city has kept the naked column intact; Mayor Landrieu has suggested that it be converted into a “water feature.” The statue (which cost $36,400 in 1876) went to the junkyard as well.

The lack of prosecutions for the aforementioned acts of vandalism (even though there is plenty of video evidence) has had a predictable effect. On May 24, another communist/anarchist group placed flyers and a hammer and chisel at the foot of a monument honoring Fr. Abram Ryan, a Roman Catholic priest, poet, and chaplain. They vandalized the monument with red paint. They did the same to the Gen. Albert Pike monument a block away. On May 31, the same group also chipped the nose off of the Lieutenant Colonel Charles Didier Dreux monument, a 1922 statue honoring the first officer from Louisiana to be killed in the War Between the States. They posted pictures of their crimes on social media and left a manifesto at the site. Monument defenders camped out in the rain to guard and clean the monument.

In the two years between Landrieu’s first announcement that he intended to remove the monuments and their actual removal, no arrests were made for vandalism, and there were no investigations of hate crimes—even when the words “Die Whites Die” were spray-painted on the base of the Lee Monument following Donald Trump’s election. The monuments have been cleaned time and again by volunteers from the Monumental Task Committee, at no expense to the city. The two-year dearth of investigation was broken after a monument supporter and his son, who painted “Gen PGT Beauregard” on the ruins of the pedestal after the statue had been taken down, were arrested and charged.

The monument-protection bill was finally passed by the Louisiana House after a lot of arm-twisting, but it continues to linger in a Republican-controlled State Senate committee; a Republican has moved to kill the bill. Meanwhile, TEDN is setting its sights on the iconic 1858 Andrew Jackson statue that stands majestically in front of the St. Louis Cathedral. The George Washington statue at the public library has been targeted. The Joan of Arc statue was also vandalized. TEDN is hoping to agitate in surrounding areas, such as neighboring Jefferson Parish, where TEDN wants to bully citizens into changing the parish name and removing tributes to the third U.S. President and chief author of the Declaration of Independence.

Perhaps TEDN has gone a bridge too far—even for craven politicians—by circulating a petition demanding that Louisiana State University do away with its Tiger mascot, in light of the fact that the Louisiana Tigers were a Confederate military unit. By TEDN’s lights, this makes LSU guilty of promoting “white supremacy.” Now they’re messing with college football, the unofficial religion of the Deep South.

Tennessee Williams placed New Orleans in a category apart from Cleveland, but one can only wonder how long it will be before New Orleans’s peculiar struggle is felt in the Midwest, as radicals fantasize about “white supremacy” in sports teams named “Browns” and “Indians” and “Cavaliers.”

Meanwhile, I look at the historical and cultural ruins of a 300-year-old city and hear the words of George Orwell ringing true:

One could not learn history from architecture any more than one could learn it from books. Statues, inscriptions, memorial stones, the names of streets—anything that might throw light upon the past had been systematically altered.

Leave a Reply