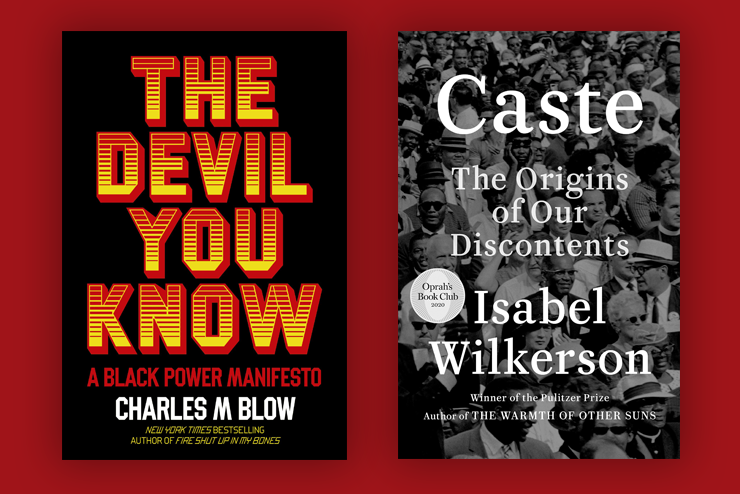

The Devil You Know: A Black Power Manifesto

by Charles Blow

Harper Collins

256 pp., $26.99

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents

by Isabel Wilkerson

Random House

496 pp., $32.00

The verbal tics of the orthodox Marxist vocabulary in mid-20th century Europe made it virtually impossible for communists to camouflage themselves. Ex-communist author Arthur Koestler vividly describes a female comrade who had almost fooled the police but then used the term “concrete” for a second time. She grew flustered when asked where she had learned this expression, and the jig was up.

Charles Blow and Isabel Wilkerson are elite members of a cultic political quasi-religion not unlike communism in many ways, and just as easily identifiable by the formulaic, fatuous language members speak as evidence of their adherence to the cult’s belief system. In this world, everything is evidence of “racism,” “white supremacy,” and “antiblackness,” and the entirety of historical American society is but a prison camp for the victims of white oppression.

Black America needs, in Blow’s terms, a “rescue mission” from systematic “white terror,” and Wilkerson describes a mercilessly repressive system in which blacks bear a caste “costume…that can never be removed.”

They are not coy about what must be done to address the problem. Blow openly calls himself an “insurgent” and cites the self-described communist Harry Belafonte—who praised the Soviet Union, Castro’s Cuba, and Hugo Chavez, as well as the work of Karl Marx—as his inspiration. Wilkerson dreams of a mushyheaded globalist collectivism in which all loyalties to kith, kin, and nation must dissolve into indistinct love for “the species,” which is best illustrated in her view by an Ethiopian runner, an African-American Olympic athlete, a “composer of Puerto Rican descent who can rap the history of the founding of America at 144 words a minute,” and the almost superhumanly annoying Greta Thunberg. America will have to submit to a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and massive reparations before we can begin to imagine an escape from caste and realize the utopia announced by the Puerto Rican speed rapper.

Hyperbole is central to this genre’s style. Wilkerson’s book begins and ends by explicitly equating America to Hitler’s Germany. Meanwhile Blow incoherently compares 20th century America’s Great Migration of blacks from South to North with the transatlantic slave trade, claiming it was a “fleeing of terror and the settling in permanent refugee camps.”

The genre is also argumentatively fueled by the anecdote and the individual case, often incompletely or inaccurately represented, as purported demonstration of the state of a more general situation.

An example of this anecdotal dependency—and perhaps the single most telling statement about Wilkerson’s book—is that she includes an entire chapter of her own experiences aboard airplanes. A flight attendant who did not leap to help her with her bag with sufficient rapidity; a passenger who would not move his bag from the overhead rack to make room for hers; yet another passenger who bumped into her while boarding: all are evidence of the “openly dismissive caste assumptions” of the pack of irredeemable racists with whom she is forced to coexist.

The impression given by this comical chapter is that Wilkerson must be an impossible person to deal with interpersonally: hostile and prepared to think the worst in every situation, eager to make baseless charges that could have significant effects on the careers and lives of those with whom she interacts, filled with resentment and diffuse anger and itching to make random others pay for it.

Even when Wilkerson wants to conclude with a hopeful anecdote, she cannot but emit the same withering scorn for anyone who fails to recognize her lofty condition or otherwise disappoints her stringent expectation. When she calls a plumber to attend to a basement leak, he appears (the horror!) in a MAGA hat. Wilkerson loathingly describes him in the terms of elite hatred of the working class—he “smell[s] of beer and tobacco” and has a “belly extend[ing] over his belt buckle”—and insinuates his evident white supremacy from the fact that he is unable to immediately correct the problem. Magnanimously, the great-souled writer deigns to try to bring the poor deplorable’s lost humanity back by informing him of the death of her mother. As I read this spectacularly oblivious bit of moral self-congratulation, I imagined tracking down this plumber and asking him for his account of this encounter. I somehow imagine it might differ from hers.

Blow is also expert in his cynical substitution of anecdote for systematic argument. He riffs on the patently absurd idea that Vermont is a particularly dangerous state for blacks. Much of the evidence he musters for this claim has to do with his own son, who, while playing football for the team at Middlebury College there, took a knee during the national anthem and was insulted by someone in the stands.

To find these arguments at all credible, the reader of this genre of black radical literature must ignore a veritable mountain of facts, including the existence of the large black middle class. The black poverty rate was just under 19 percent in 2019, according to Census data, about twice that of the white poverty rate. This kind of figure is endlessly cited in this literature. But of course it also means that more than eight in 10 black households were not in poverty. By that same data, nearly half of black households had incomes greater than $50,000, and thus were solidly middle class or higher.

above: Charles Blow, The New York Times columnist and author, delivers the 2019 Hearst Lecture at Moody College of Communication at the University of Texas, Austin. (Flcikr/Moody College of Communication CC BY-SA 2.0)

The susceptible reader must also believe that police kill large numbers of unarmed blacks daily. But this is pure myth. In all of 2015, for example, the national total was 38 deaths. We have figures from that same year for all police interactions with civilians and when we compare that to the tiny number of lethal encounters, we learn that the odds of an unarmed black person age 16 or older being killed by police were almost literally one in a million. Furthermore, the risk for all Americans of dying in a fall is about 100 times higher than the black risk of being an unarmed victim of lethal police violence. It is an insanely irresponsible exaggeration to present this as something to be reasonably feared by the average law-abiding black American. There is next to no chance that it will happen to you, especially if you refrain from doing the reckless things that nearly always precipitate such situations, such as failing to show police your hands or fighting them.

Finally, that gullible reader must also believe blacks are systematically excluded from schools and places of employment. He must be radically ignorant of the extensive, torturous efforts of virtually every educational institution and employment industry to actively recruit and bring on board as many blacks as possible, often with qualifications below those of other applicants.

Blow’s book at least has the advantage that it advocates for something—the migration of Northern blacks to the South—that is already happening, though only in dribs and drabs. But his claims about the situation of blacks in both North and South are egregiously false. The most impressive period of black economic gain in the country came precisely during the time of the Great Migration. The black poverty rate was cut in half between 1940 and 1960, dropping 40 percentage points at the height of the second black migratory wave and well before the biggest events in the Civil Rights movement. The growth of the black middle class was also much greater during the years of this second migration than during subsequent Civil Rights years; the percentages of black men and women in white-collar jobs grew four- and sixfold respectively between 1940 and 1970.

The assumption behind Blow’s hyperbole is that only the total disappearance of all racial disparities is an acceptable outcome, and all problems and pathologies found in black communities are due to racism. Detroit fell apart, we are to believe, because of white flight, and not because of the predominantly black rioting and crime that they fled. He describes a conversation with the mother of Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old shot by police while wielding a replica toy gun, and notes that her family’s history is one filled with “drugs and violence.” Oddly, no one in her family can be assigned any agency at all in this dismal fact.

This is a despicably anti-black position, at its core. In this view, black people never have any free will to act or to refrain from acting. They are puppets controlled by machinations they do not understand. Was even the most ruthless Southern slaveholder this dismissive of the basic human freedom of blacks? It’s a real question.

Blow presents majority black Southern cities as unquestionable success stories and desirable destinations for migrants. But the 2019 murder rate contradicts this as every one of those cities ranks in the top 50 in the country, and all but Savannah and Montgomery are in the top 25. Five of the top 10 American cities for murder rates in 2019, and six of the top 11, were majority black cities in the South. But, we can rest assured, the logic of Blow’s faith would dictate that this, too, must be the fault of white racism.

Blow also fails utterly to reckon with the cultural forces necessary to make viable, successful black cities in the South or elsewhere. He invokes black cultural tradition as a good thing, but then he attacks the black church and religious faith as “indoctrination” and approvingly cites Marx’s “opiate of the masses” phrase. It is an “end of hoping” that Blow wants.

above: Isabel Wilkerson speaks at the University of Virginia in 2011 (Flickr/Miller Center, CC BY 2.0)

Wilkerson believes the U.S. is one of three model caste systems in human history (India and Nazi Germany are the others). But in classic social science frameworks, caste societies require all members to be casted into unchanging groups. By this definition, only precolonial India and apartheid South Africa fit. Numerous other examples—the slavery-era U.S., feudal Japan, a number of African societies—have or had durable minority pariah groups, but the rest of the society is not casted.

The argument that blacks were a caste in America during slavery is sustainable, but Wilkerson’s claim is that the term adequately describes American blacks now. Consider this claim in light of these two black writers who, to judge from their book sales and job titles, draw incomes that place them in the upper 5 percent or higher, who are fêted by elite cultural institutions that ceaselessly tell them how amazingly smart they are and ask them breathlessly for more, and who have gained their positions by telling readers that the country in which they live dooms people like them to a permanently inferior status. Raucous laughter is the only fitting response.

Wilkerson also believes rigorous in-group/out-group antagonism was invented by the religious systems of the Indian subcontinent and Europe. Yet the Iroquois Confederacy carried out a war of extermination against the Huron and the Mexica, exercising crushing military domination that included slavery and human sacrifice over neighboring ethnic groups with no ideological contribution whatsoever from Hinduism or Christianity. Durable forms of social order based on caste date from at least the beginning of horticulture, roughly 10,000 years ago. Slavery of a hereditary nature existed in some societies even before that. The history of humankind is full of such things. Mature adults generally learn to come to terms with this.

But the goal for Blow and Wilkerson is not truth. There is an audience for this kind of thing, and it is a sizable one that buys books and pays to attend talks and invite speakers. It is made up mostly of guilt-ridden, upper middle-class whites, the kind of folks who sit happily and pensively listening to others tell them how undeserved and unjust their social position is. If I could only believe that Blow and Wilkerson might convince some portion of that morbidly self-execrating white elite to willingly dispossess themselves, I could finally point to something to celebrate in their project, as I admit that I find many of those people at least as insufferable as they do, but for different reasons.

It can be good fun to decry the many failings of this genre of political literature, but then there are its consequences. We hear constantly that “racist rhetoric” causes hate crimes. With that same causal linguistic theory, we can predict that one outcome of books like these is violence. The deceitful, hateful words Blow and Wilkerson have produced will embolden those among the racially aggrieved, predisposed to engage in riots and acts of criminal and terrorist violence such as those that left many police officers dead in Texas and Louisiana a few years ago. They will inspire black youth to reject the very idea of trying to better themselves and instead to retreat further into helpless, angry victimization and to lash out against “oppressors.” That will be the most important legacy of Blow and Wilkerson’s morally crippled literature.

The sad phenomenon of black elites preaching to their fellows that America despises them and wants their ruin, when they are themselves evidence of the falsehood of the claims, is something this country is going to have to outgrow. If it does not, the cancer of racial grievance will eventually tear it apart.

Leave a Reply