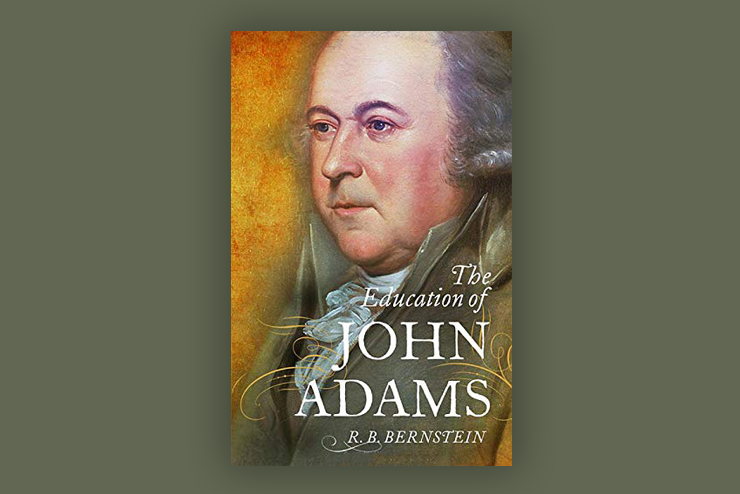

The Education of John Adams; by R. B. Bernstein; Oxford University Press; 368 pp., $24.95

It is not fashionable these days to admire the Founding Fathers, and yet the flood of books, articles, and even Broadway musicals devoted to them has not ceased. Attention is usually focused on George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jeff erson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison, but, lately, the stock of the somehow more obscure John Adams—signer of the Declaration of Independence, our fi rst vice president and second president, and the first incumbent to lose a presidential election—has been rising.

Adams was the most intellectual of the founding generation, and wrote now unreadable multi-volume treatises on subjects such as comparative constitutional law. His correspondence with his wife, Abigail, to whom he was married for more than five decades, is one of the great sources of insight into early republican love, domestic life, and even feminism.

Adams is also intriguing because he was always his own worst enemy—envious of those who succeeded in society with apparently less eff ort than himself, such as Franklin, or those, like Washington, whose natural charisma, grandeur, and military bearing made him an exceptionally tough act to follow. Worried that to alter Washington’s cabinet would be a slight to the father of his country, Adams left in place advisors who were more loyal to Alexander Hamilton—Washington’s treasury secretary and the leading force in his administration—than they were to Adams. Even so, Adams somehow managed to alienate Hamilton, and Hamilton’s derogatory comments about Adams, which were published on the eve of the election of 1800, contributed to Adams’ later loss of the presidency to Jefferson.

R. B. Bernstein, one of our most talented legal and constitutional historians and one of the few who is also a gift ed biographer (his superb book on Thomas Jefferson is a companion volume to this one), sought to create not simply a portrait of Adams as an irascible eccentric or as a deep scholar—the two lines of Adams’ biography currently in vogue—but to combine both in a work that would also explore, more than any previous effort, Adams’ views on law, slavery, and race.

Bernstein succeeds on his own terms, as this volume is also the most concise, elegant, and best-written introduction to Adams and his time we are ever likely to receive. His exceptionally fulsome annotations demonstrate Bernstein has read, digested, and incorporated a remarkable range of secondary literature on early American law, politics, and culture. Not only that, but he also has a masterful command of primary sources, particularly Adams’ correspondence and writing. This allows Adams to speak for himself, making him quite a bit more appealing to readers than he may actually have been.

Even so, Bernstein does not ignore Adams’ failings, but through their enumeration, manages to make Adams more endearing.

Bernstein set out to place Adams and his views in context, and a rich context it is: the Revolutionary War, a diplomatic tour of European capitals, ascendance to the highest national office, an on-again off-again intimate friendship with Jefferson, and the strained relations with others who also occupied the highest pantheon in early American history.

The most impressive feature of the book, though, is the exploration of Adams as a political and constitutional philosopher. Some of us would like to think that the original understanding of the Constitution’s framers can be easily grasped, and that there is a single set of tenets of that original understanding that could be confidently applied by Supreme Court justices, if they were only faithful adherents to the rule of law.

Some, like Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas (and your reviewer), cling to that view, but Bernstein suggests that during Adams’ time there were actually several competing constitutional visions.

John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, Bernstein explains, “championed a version of constitutionalism imbued with the Quaker faith, promoting peaceful dissent as the best way to preserve rights and liberties.” Thomas Paine “proposed a competing model of constitutionalism, grounded in popular government and embracing simplicity of constitutional ideas and structures,” while James Madison “advocated a form of constitutionalism emphasizing the balance between state sovereignty and national supremacy within a federal system, a concept that Adams never fully understood.”

Jefferson, like Paine and Franklin, “sought to promote the international democratic revolution ignited by the American Revolution,” while Alexander Hamilton and John Jay “offered a nationalist constitutionalism empowering a supreme general government both to restrain states’ political powers and to create a great commercial republic for a union that could stand the test of time.”

Adams’ vision, somewhat different from all of these, was deployed throughout his life, as he “sought to preserve Anglo-American common-law constitutionalism, in particular its commitment to separation of powers and checks and balances.”

John Adams by Gilbert Stuart, oil on canvas, c. 1800/1815 (National Gallery of Art/Wikimedia Commons)

As a student of world history, Adams thought some aristocratic elements in society were inevitable, and he thus became an easy target for Paine and Jefferson, who believed the future lay with democracy rather than monarchy or aristocracy. In a splendid piece of invective to a correspondent in 1805, Adams dismissed Paine as “a mongrel between Pigg and Puppy, begotten by a wild Boar on a Bitch Wolf, never before in any Age of the World was suffered by the Poltroonery of mankind, to run through such a career of mischief.”

Adams also, in a revealing and exasperated outburst, suggested that Paine’s “Age of Reason,” was really the “Age of Paine,” characterized by “Folly, Vice, Frenzy, Fury, Brutality, Daemons, Buonaparte,” and Paine himself.

Bernstein demonstrates that Adams simply was unable to grasp the increasingly democratic nature of his own country. That inability, coupled with Adams’ failure to be convinced of the value of federalism (dual national and state sovereignty), which was so important to Madison and Jefferson, led our greatest living American founding era historian, Gordon Wood, to wonder whether Adams simply became “irrelevant.”

Adams was not irrelevant, however, as Bernstein makes clear that Adams’ work on constitutional theory had a profound influence not only on the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, which Bernstein properly calls “the most eloquent state constitution framed during the Revolution,” but also on the framing of the federal Constitution of 1789. Moreover, in the last 30 years, through the influence of many historians and political scientists— and Justices Thomas and Scalia in particparticular— we have come to a greater appreciation of the federal Constitution’s reliance on English common law, as well as the separation of powers and checks and balances that were so important to Adams. The man may still be of lasting relevance after all.

Bernstein is not actually an Adams hagiographer—his excuse for writing yet another biography of Adams is that he has special legal expertise—but I believe he has succeeded in humanizing Adams greatly. For example, I knew Adams was more religious than some other founders, and I knew that Adams had rekindled his friendship with Jefferson following the bitter political battle between the two over the presidency in 1800, but until I encountered Bernstein’s account, I hadn’t realized how poignant was their shared piety and shared belief in an afterlife.

When his beloved Abigail passed away in 1818, Adams wrote Jefferson, “If human Life is a Bubble, no matter how Soon it breaks. If it is as I firmly believe an immortal Existence We ought patiently to wait the Instructions of the great Teacher.” Jefferson wrote back, “It is of some comfort to us both that the term is not very distant at which we are to deposit, in the same cerement, our sorrows and suffering bodies, and to ascend in essence to an ecstatic meeting with the friends we have loved & lost and whom we shall still love and never lose again.” The popular conception among scholars that our Founding Fathers were a collection of deists, agnostics, and atheists needs amending.

It is not too much, then, to be deeply grateful for this sensitive, but realistic and very rich account of Adams and his times. This book shows that for the founding generation there was a profound connection between constitutional law, morality, and religion. Bernstein eloquently demonstrates that Adams’ personal flaws and his lack of political finesse and popularity pale in comparison to the rich constitutional legacy he left his nation.

Bernstein gave the book its title to recall Adams’ great grandson Henry’s marvelous conservative reflection on the decline of the country in the 19th century. Bernstein reveals little, in this fine work, of his own political views, though he is anything but a Trump supporter. Yet, insofar as Trump is a follower of Adams’ favored schemes of the separation of powers and checks and balances on the power of Washington, D.C., his book may actually be a manual for appreciation of that other irascible and parvenu president.

Leave a Reply