Martin Fletcher worked seven years as a Washington, D.C., correspondent for the London Times. Before returning to Britain, he packed up a car and hit the road for a five-month journey that started in Virginia and ended in Seattle. After years of writing about politics in Washington, Fletcher “resolved to take time off to explore this overlooked land more deeply, to travel far beyond the famous sights and cities in search of this little-known America.” Along the way, he gathered enough material to write a book.

When a European writes a book about rural America, you can bet it will feature detailed accounts of the nutty inhabitants of the hinterlands flanked by New York and Los Angeles. To the European mind, America is a giant freak show, overrun by philistines, inbreds, and gun-lovers. Like busy little worker ants, Europeans are building a bureaucratic superstate that has very little room for the backward notions of individualism and freedom that many Americans still treasure. Of course, these cultural differences cut both ways. Unlike the French, most Americans are not attracted by the scent of unwashed armpit, and unlike Englishmen, most American men still prefer women over sheep.

Fletcher observes enough Americana to delight the legions of Europe-builders in Brussels. He tracks moonshiners. He attends a church service where parishioners handle poisonous snakes and drink strychnine. He interviews UFO chasers and conspiracy theorists. And, at almost every stop along the trip (save maybe his visit to a Nevada bordello). Fletcher confronts Christians so fundamentalist that, to his amazement, they actually believe in creationism.

Fletcher is no creationist. And he is definitely bothered by some of the beliefs and customs of Heartland America. Even so, it’s obvious Fletcher likes a lot of what he sees. He is also honest. In reflecting on one white Southerner’s view that a public-housing complex was an “incubator” where blacks on welfare “made babies” and his opinion that young black youths in flashy cars outside a store were crack dealers, Fletcher says, “In both instances he was probably right.” At a stop in Alabama, Fletcher recalls an earlier visit he made in 1996 to investigate an epidemic of black church burnings that turned out to be as fictitious as the Loch Ness monster:

Along with scores of other reporters from Washington and New York I flew in for a day to write what seemed a straightforward story about how white racists, emulating the “night riders” of the KKK during the civil rights era, were destroying the traditional centres of rural black life.

Local black leaders certainly encouraged us in that belief. . . That all happened, however, before the charges of corruption and mismanagement by the county’s black officials came to light, and I began to wonder whether the media had not been hoodwinked.

Indeed, the media were hoodwinked. And to Fletcher’s credit, he can admit to having been taken for a ride by a band of ideological con men.

Fletcher’s strength is reporting: It makes Almost Heaven a simple, easy-to-follow account of a traveler who wandered from the South to the Northwest. But reporting, as anyone who reads a newspaper will know, is often bland and shallow, weaknesses from which Almost Heaven suffers at times.

The main problem with the book is that Martin Fletcher had his mind made up about the Flyover Republic before he filled his first tank of gas. In the opening pages, he writes that inner America

is an extraordinarily insular and conservative place whose inhabitants consider New York and Washington as foreign as London and Paris. . . . In much of this land even USA Today is unobtainable and ultra rightwing radio chat-show hosts are often the major source of “news.”

Well, most large cities are pretty insular, also. For every urbanite who visits the symphony, the art museum, or the foreign-film theater, dozens more take a first-class ride to Jerry Springerland. And all cities harbor at least one area where it’s easier to catch a bullet or score drugs than it is to find a USA Today “news” box.

It’s one thing to say that rural America is “insular” and “conservative,” and quite another thing to prove it. Countless heroes of the American left hail from the Heartland. South Dakota has given us Senators Daschle and McGovern. Texas hoisted Great Society Lyndon. And Georgia produced Jimmy Carter. Fletcher ignores this. He then contradicts his claim that rural America is wall-to-wall conservatives, by describing first a church service at which Jimmy Carter preached and later a visit to Hope, Arkansas, birthplace of the notorious right-wing conservative Bill Clinton. And the contradictions continue to pile up. How, for example, are West Virginian bear-hunters who use high-tech tracking equipment or Indians with satellite dishes insular? And could it really be that the all-black communities he visits are conservative? For that matter, are all the Christians he meets conservative just because they are Christian?

As a European journalist, Fletcher is what he is. Because Europeans get a kick out of these exotic creatures, he goes out of his way to hunt up white separatists, antigovernment militia men, and weirdos who believe the U.S. government is in league with agents from outer space. If your only knowledge about America came solely from this book, you would think the country were flowing over with antigovernment loons. The reality is that vastly more Americans simply believe their government is a stupid, lumbering behemoth that constantly steps on little people while shielding the corrupt and the lazy.

A more interesting book would explore the thousands of Americas flourishing under a political system that is under assault by the homogenizers. It would survey a land that tolerates diverse beliefs and backgrounds. In short, it would have been written by somebody who didn’t treat America like a giant zoo.

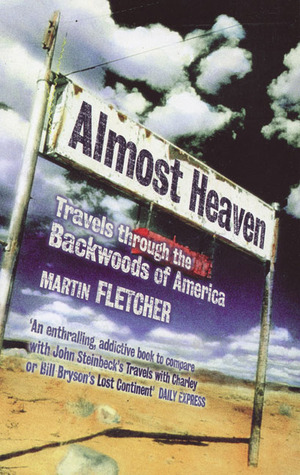

[Almost Heaven: Travels Through the Backwoods of America, by Martin Fletcher (London: Little, Brown and Company) 304 pp.. $14.95]

Leave a Reply