Poet John Clare (1793-1864) seems to have grown from the soil. His last name derives from the word clayer—someone who manures and enriches clay. As a farm laborer, he drew sustenance from the earth. Immersed in humus, he learned the humility so necessary to creativity. His poems, like furrow lines, break the surface of things to expose the extraordinary aspect of the ordinary. Delighting in common things—birds, flowers, trees, blades of grass—Clare revels in their simple mystery. It is an art that captures the first day forever dawning.

John Clare was born in Helpston in Northamptonshire, a small village largely undisturbed since the Middle Ages. People kept the old ways and customs, shared the common land, and still observed the pre-Reformation calendar that celebrated all the seasonal festivals. Life was in rhythm with nature, in an era before the Enclosure Acts took their toll and radically reconstructed English rural life.

The Clare family subsisted as farm laborers, living on potatoes and water gruel. When only seven, Clare had a job looking after sheep and geese. At 12, he worked the fields. Never robust in health or temperament, he stood barely five feet five inches, a small, sensitive plant. One reviewer who visited him at Northborough sanitarium described his eyes as “light blue and flashing with genius.”

Clare was reared in an oral tradition of stories and songs. His parents were admired as local storytellers: Clare’s father once said he could sing over a hundred songs. When his workday was finished, Clare studied reading and writing in night classes. At 13, he came across Thompson’s poem “Seasons” and was immensely influenced by it. Thereafter, he read every book he could find, recited poetry to himself in the fields, and wrote verses of his own on discarded scraps of paper.

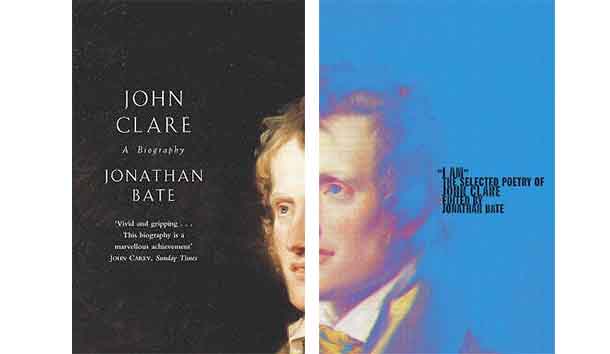

Jonathan Bate does a fine job in reacquainting us with this sadly neglected Romantic poet. The noted Shakespeare scholar spent five years among Clare’s vast archive, determined to fill a void by giving “the one major English poet never to have received a biography worthy of his memory” his due. Bate has succeeded absolutely in his prescribed biographical task.

Published alongside this biography is a companion volume containing a wider selection of poems. I AM takes its title from one of Clare’s most anthologized poems:

I am—yet what I am, none cares or knows;

My friends forsake me like a memory lost:

I am the self-consumer of my woes;

They rise and vanish in oblivion’s host

Like shadows in love’s frenzied stifled throes:

And yet I am and live as vapours tossed.

“I AM” was written at the Northampton general lunatic asylum, to which Clare was committed in 1841. Here he spent the rest of his life imagining at times that he was Lord Byron or a prizefighter or that he was married to his childhood sweetheart, Mary, who was a kind of elusive muse for him. What happened to Clare and what he suffered from is still open to speculation. Bate says, “if Clare were alive and receiving psychiatric treatment today he would probably be diagnosed as suffering from manic depression.” Another doctor’s diagnosis mentions exhaustion from “years spent addicted to poetical prosings.”

The world seemed to close in on poor Clare. After his initial success as a poet with the publication of Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery in 1820, Clare married, as his publishers Taylor and Hessey, ever mindful of the example of Robert Burns, had urged him to do. (Clare, like Burns, was overly fond of women and drink.) Patty Turner and John Clare had seven children. Some of the local nobility helped with a generous income of 45 pounds per year, but that was not enough to support Clare’s household, which included his parents

Clare’s second volume made a respectable showing. In London, he met Coleridge, Lamb, De Quincy, and Haz-litt, but the “peasant poet” rapidly fell out of fashion and was left between two worlds. Looking out of his coach at the laborers in the field, he wrote,

The novelty created strange feelings that I could almost fancy that my identity as well as my occupation had changed—that I was not the same John Clare, but that some stranger had jumped into my skin.

Clare drove himself hard to support his growing family and never ceased writing poetry. Prolific as his output was, his books never sold enough to bring the income he needed.

And the fields he loved were being enclosed for the sake of the industrial efficiency of capitalist agriculture. Between 1760 and 1815, some seven million acres of English common land were made private.

Fence now meets fence in owners’ little bounds

Of field and meadow large as garden grounds,

In little parcels little minds to please

With men and flocks imprisoned, ill at ease.

The chase of money was in full swing along with the Enlightenment project to reduce all of Creation to a base materialism. A genuine poet, Clare stood against this cloying conformity. “I am as far as politics is concerned for King and Country—no Innovations in Religion and government say I.” Yet Clare saw the rapid change around him. He was surrounded by a new people, who “Deem all as rude their kindred did of yore” and who engage in “Affecting high life’s airs to scorn the past / Trying to be something makes them nought at last.”

Tormented by what he called “blue devils” and the encroaching ache of modernity, Clare took refuge in his own world.

Old custom! O I love the sound,

However simple they may be—

Whate’er with time hath sanction found

Is welcome and is dear to me—

Pride grows above simplicity

And spurns them from her haughty mind

And soon the poet’s song will be

The only refuge they can find.

Clare’s work is only now receiving the attention it deserves. His “Shepherds Calendar,” Bate argues, “is one of the greatest poems of the nineteenth century.” With this new biography and selection of poems, Clare’s work is lifted into the realm of the eternal.

A Vision

I lost the love of heaven above;

I spurned the lust of earth below;

I felt the sweets of fancied love,

And hell itself my only foe.

I lost earth’s joys but felt the glow

Of heaven’s flame abound in me;

Till loveliness and I did grow

The bard of immortality.

I loved but woman fell away;

I hid me from her faded fame:

I snatched the sun’s eternal ray

And wrote till earth was but a name.

In every language upon earth,

On every shore, o’er every sea,

I gave my name immortal birth

And kept my spirit with the free.

[John Clare: A Biography, by Jonathan Bate (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux) 672 pp., $40.00]

[“I AM”: The Selected Poetry, of John Clare, edited by Jonathan Bate (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux) 344 pp., $17.00]

Leave a Reply