William Butler Yeats was not talking about literally sailing to a literal Byzantium in his famous poem, and I know that Urbino is a mountain fastness, not a port. Even so, sailing to Urbino is necessary, and it does not matter how you do it—only that you do. One way to approach Urbino is through the mediation of June Osborne (lecturer, author, art historian, and former research assistant to Ernst Gombrich, the greatest art historian of all time), who has written the first book on Urbino in English.

My own approach to Urbino, as I remember from some four decades ago, was different and accidental. I was reading poetry, and I wanted to understand both the letter and the spirit of what I was reading.

And Guidobaldo, when he made

That grammar school of courtesies

Where wit and beauty learned their trade

Upon Urbino’s windy hill,

Had sent no runners to and fro

That he might learn the shepherds’ will.

These lines, and others from the poem “To a Wealthy Man who promised a Second Subscription to the Dublin Municipal Gallery if it were proved the People wanted Pictures,” were inspired by the Italian Renaissance in general and Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano (The Book of the Courtier, 1528) in particular, as Yeats meditated on the clash between artistic ideals and democratic politics in the Dublin of 1913. Castiglione’s beautiful book meant much to Yeats, as in his poem “The People,” where Urbino is cited again, as an image and an ideal of community and aristocratic life. Yeats’ citations and passionate devotion are one way to approach Castiglione, who, of course, set his superb dialogues in Urbino, whose court was, in his informed opinion, the finest and the most cultivated in Europe.

By the time Castiglione wrote of it, that court’s best years were already becoming a memory; it was to fix that memory forever that Castiglione made his book. The great courtiers died as he inscribed, but the memory of the culture he had known in the ducal court of Urbino became for Europe an ideal of the good life. The High Renaissance spread to France through the influence of Castiglione, who had known François I, who is cited in his book, before he became king. And through Hoby’s translation of 1561, the image of the Renaissance man was fixed in England by such examples as Sir Philip Sidney, the man of letters who died as a soldier, and the tragic Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, who was trapped in an unworthy court.

June Osborne has taken for her subject not the glorious book but the reality that inspired it, its roots in the Roman dispensation and the medieval period, and the flowering under the leadership of Guidobaldo’s father, Frederico da Montefeltro, count and then duke of Urbino, who assumed power in 1444 and died in 1482. A highly successful condottiere, Frederico made a lot of money for decades both by fighting and by not fighting. He knew what to do with his wealth—his leadership and patronage were what made Urbino both a glorious reality and a legend.

Duke Frederico was and is a supreme example of an enlightened monarch. He stayed in close touch with the people he ruled and was not at all grand in his style of address. He said that the secret of leadership was “essere umano,”—to be human, and also to be humane. We find this humanity in his personality, in his patronage, and in his social relations. His household amounted to 500 people, including 45 counts; four teachers of grammar, logic, and philosophy; two dancing masters; two fencing masters; two organists; eight masters of horse; and one “Keeper of the Camel-leopard” (or giraffe). My favorite work of art at the palace is Frederico’s bed, but there were more glamorous accomplishments. Artists who worked at Urbino in his time included Justus of Ghent, Piero della Francesca, and Paolo Uccello; later, Raphael and Titian painted portraits of the dukes and duchesses of Urbino. Though it is impossible to overlook such distinguished contributions, even such a level of achievement is not quite the supreme plane on which the measure of Urbino may be attempted.

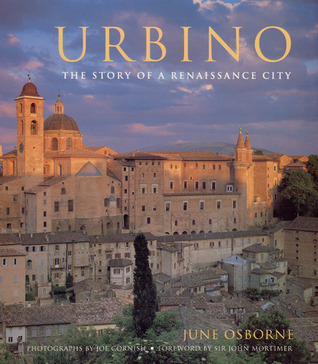

The Ducal Palace and its integration into the town says much about the social cohesion of that community in its greatest days. The luminous beauty of the stonework and the siting of the town itself all speak to something more grand even than great works of art—I mean the vision of Urbino as an exalted image of the ideal community, of the Yeatsian Unity of Being. Castiglione alluded to Plato and Aristotle in his dialogues; Duke Frederico was a patron of learning who amassed a superb library and whose Studiolo was decorated with pictures of the masters of learning and wisdom, such as Moses and Solomon, Homer and Virgil, Boethius and St. Thomas Aquinas.

Now having said so much, let me add that “to be human” means also to be flawed. The glory of Urbino had its source in revenues derived from violence, and there remains the possibility (if no more) that Frederico’s accession to the throne may have implied his own foreknowledge of the assassination of his half-brother, Oddantonio. And I will add that, although the synagogue in Urbino is centrally located and Jews were a notable part of the town’s commercial life, the antisemitic predella, The Profanation of the Host by Uccello, can only be accounted a perversely twisted product of the imagination and an unworthy, because groundless and cruel, subject for art.

To me, the best thing about Urbino is its scale. In this, it is truly human, for not being monumentally overbearing. Urbino lives on in its beauty and in its university, founded by Guidobaldo in the early 16th century. We need to maintain contact with Urbino if we wish to maintain a connection with our own beleaguered humanity. For helping us to do that in all the fullness of the tale and in the splendor of its illustrations, we must be obliged to June Osborne and her colleagues.

[Urbino: The Story of a Renaissance City, by June Osborne (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 208 pp., $50.00]

Leave a Reply