“Truth rests with God alone, and a little bit with me.”

—Yiddish Proverb

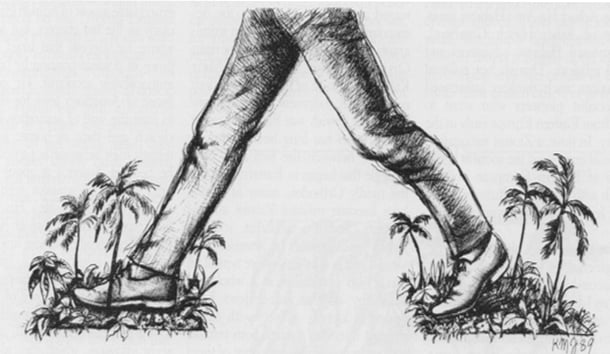

Moshe Leshem ends Balaam’s Curse with a warning against the growing political power of the Israeli Orthodox rabbinate. By yielding to Orthodox authorities on educational and cultural matters, he says, Israelis are sacrificing their democratic patrimony. For the sake of Israeli democracy and of the country’s future relations with other nation states, Leshem urges that Israel perform a separation of church and state. This would mean that Israelis would treat religion as a private matter and, among other things, accord to the leaders of Reform and Conservative Judaism full parity with the now established Orthodox rabbinate. Only through such reforms, Leshem insists, can Israelis avert the dubious blessing—in reality a curse—that the gentile prophet Balaam pronounced upon their ancestors in the desert: “Lo, the people shall dwell alone, and shall not be reckoned among the nations” (Numbers 23:9).

Leshem’s brief against the Orthodox in Israel overlooks certain cultural realities. Such massive interference with religious-cultural patterns would certainly offend most Israelis outside the intelligentsia. The (misnamed) Conservative and Reformed Jewish movements in Israel are made-in-America imports; they have little or no support even among Israeli secularists and are now being used to impose feminist social agendas on unwilling Israelis. When the Masortim (Conservative Jews in Israel) held services at the Western Wall conducted by women in prayer shawls, onlookers were outraged.

Despite his shrieks against organized religion, Leshem is informative on the subject of the ideological origins of the Jewish state. He correctly notes that among the Zionists who originally envisaged the creation of Israel, three different and conflicting concepts were considered. The oldest—as well as the first to be abandoned—was the idea of a Jewish state constructed by the late-19th-century Viennese journalist Theodor Herzl. As a German-speaking Central European Jew, Herzl obviously had no interest in preserving the rabbinically controlled communal life of the Eastern European Pale of Settlement. He dreamt of a Jewish state that would free his coreligionists not only from anti-Semitic Russian officials but also from the “ungentlemanly” backwardness of their own culture. The New Jew would speak German, watch clocks and mind his manners, appreciate art and take part in sports. Leshem is at his best depicting Herzl’s entry into an Eastern European Jewish town, whose inhabitants rush forth to hail him as their king. Suddenly Herzl pulls out a watch—a mechanism despised by the townsmen as a gentile invention—and lectures to his disillusioned listeners on the importance of time.

For most Eastern European Zionists, the group that founded (and, despite the present Oriental Jewish majority, still politically dominates) the state of Israel, Herzl was a “cold” and “alien” presence, the embodiment of a German-Jewish ethos unrelated to their cultural experience. More typical of later Zionists were cultural nationalists like Achad Ha-Am (Hebrew pseudonym of Asher Hirsch Ginzberg), who stressed Hebrew education and ethical religion. Though not political nationalists, such thinkers influenced the socialist pioneers who went to Israel from Eastern Europe early in the century. In time, a Zionist nationalism arose that combined the socialist agrarianism of Eastern European political radicals with Hebrew culture as a vehicle of Jewish national consciousness.

The third model, although one neglected by Jewish intellectuals, and discussed by Leshem only in passing, may have been the most important, based as it was on the vision of the Eastern European Jewish masses finally embracing the idea of a Jewish homeland. Though tensions grew between the rabbinical magisterium and the Zionist leaders who were generally contemptuous of religious orthodoxy, most Eastern European Jews, Leshem stresses, associated any specifically Jewish state with the continuation of an Eastern European Jewish community, freed of gentile persecutors. Though these masses distrusted the German Jews who sought to Westernize them, they also never fully accepted the secular, educationist Zionism of their own radicalized intellectuals.

It may be fair to say, though Leshem never carries his analysis quite far enough, that the present Israeli Kulturkampf represents a clash between two Eastern European concepts of Zionism. While Herzl’s model never gained ground in Israel owing to the marginality of German-Jewish cultural and political ideas, it did nevertheless influence the thinking of American Jewry. If expressions of Jewish hostility toward “Christian America” have grown louder and more obsessive in recent years, this may be partly due to the disappearance in America of the old German-Jewish establishment. Like the lace-curtain-Irish, this establishment acted as a moderating force on later and more socially resentful immigrants. It stressed civility and patriotism and would have shunned the present competition among American Jews and others for the top spot on the federal government’s list of socially accredited victims.

The war between Israeli secularists and the embattled Orthodox is being waged almost, entirely among the descendants of Eastern European immigrants. The intervention of American Orthodox Jews, like Rabbi Meir Kahane and most of his followers, does not call this judgment into question. The same Jewish war that has broken out in Israel has long been raging in America between the two sides of a struggle that began in Eastern Europe: the rigidly Orthodox, many of whom have become militant Zionist annexationists, and the secularist, socialist Jewish intelligentsia. In America, the second group is by now more typical of the Jewish population as a whole; in Israel, by contrast, most Jews have ceased to identify actively with either militant minority, though both remain politically powerful on account of their organizational and electoral skills.

Unlike Leshem, who writes as a partisan secularist fearful that his own side may be losing, I suspect that the conflicts he describes may soon be passé in Israel. The majority of the country, as sociologist David Elazar notes, is made up of Sephardim, Mediterranean rather than Eastern European Jews. Though Sephardim have strong communal ties, they have never been as zealously and legalistically Orthodox as their Eastern European coreligionists. They also bear no resentment against the Christian West, looking to that civilization as a natural ally against the Arab Moslems, who expelled them and their families from the Levant and North Africa. Sephardim, moreover, have never had a romance with Marxism or socialism and despise even the watered-down collectivism preached by the Israeli Labor Party and by Histadrut (an umbrella union organization). Israeli Sephardim vote for the right, as Leon Hadar (a Sephardic political analyst) shows, because of their treatment as social outcasts by the Labor Party leadership and because of the vicious persecution they suffered in Arab states. Sephardim, most importantly, do not fall into either of the two warring camps that came out of Eastern Europe and are still to be found in Israel and America. That fact, at least, should bode well for the future of Israel.

Perhaps it may be necessary to call attention here to Leshem’s unfortunate habit of treating religion as an expendable aspect of human life. Particularly in the last chapter, but also elsewhere, he suggests that Israel will improve its political position by becoming immaculately secularist. He is full of praise of American Jews for struggling to raise the wall of separation between church and state at home; and even regards their behavior as patriotic, since he believes America is about “pluralism” (which he equates with driving religion from public life). His views in this respect overlap those of American Jewish liberals who likewise link political conflict to religion. Like him, they believe that the first will die out only if the second can be disposed of Liberals in general have always blamed religion for the perpetuation of social, racial, and sexist injustices, which they identify as the fundamental causes of war. Therefore, they seek to supplant religion with various humanist formulas that they believe Judaism, despite its historically patriarchal, theocentric, and nationalistic nature, must somehow convey. In an anguished statement deploring the direction of Israeli politics, Jewish liberal activist and movie star Richard Dreyfus has observed: “I was raised to believe that Jews have to be better than others, to be the ultimate moral example to the world. We cannot be silent. Being silent forty years ago meant being a good German.” Going beyond the obligatory reference to a German nation of robots and to the “lesson of the Holocaust,” Dreyfus here engages in the characteristically Jewish liberal practice of linking the idea of Jewish superiority to an anti-political universalism. Presumably Israel’s geopolitical difficulties could be solved by bringing Israeli soldiers to a party at the swimming pool where Dreyfus holds his next interview. There they could listen to his oracular autotherapeutic assortment of dangling participles. Meanwhile, Leshem could invite the ACLU into his country, in order to insulate it against the rhetoric of crazy religious enthusiasts. One would be justified in asking how these gestures might keep Israel’s sworn enemies from blowing her up. The question is, of course, an impudent one: what is to be protected is the future of an illusion of the Enlightenment, not the physical security of a nation with armed enemies just beyond its borders and a large Arab minority—much of it sympathetic to Israel’s foreign enemies—within them.

A variation on the Dreyfus-Leshem view of Israel’s mission as a Jewish state can be found, curiously enough, among the neoconservatives. Although they defend Israel furiously against all critics, Norman Podhoretz and his circle dream alike of a brave new world without politics. In this world, which they imagine already largely exists, nations and national interest will cease to operate; everyone will think like a neoconservative. Israelis will not have to prepare for this secularized Kingdom of God, since global democracy attaches to them irretrievably, like grace to the faithful in Calvinist theology. The truth that will never pass neoconservative lips is that Israel is not a secular pluralistic democracy. Nor is there any reason that it should be. Judaism has a time-bound relationship to the Enlightenment: one limited to its quest for a defensive strategy against Christian anti-Semitism, and to the war in Eastern and Central Europe being waged by Jewish secularists against the rabbinical magisterium.

Leshem, who may have spent too much time among ethical culturists, exaggerates the Jewish ties to Enlightened thinking. Like the authors of the Israeli Declaration of Independence, he anachronistically finds such thinking in Prophetic (as opposed to Rabbinic) Judaism, wishing us not to notice the messianic and often xenophobic nationalism, mystical utterances, and—especially in the case of Ezekiel—profound attachment to the priestly cult in the Prophets, as well as in later Judaism. Leshem even works hard to turn Herzl into a French “philosophe manqué,” though, as his biographers point out, Herzl took his ideas more from the gentrified German bourgeoisie than from the Age of Reason.

Unfortunately for Leshem, there is no reason to assume that all Jews at all times will (or should) accept cosmopolitan, egalitarian values; as he himself regretfully admits, these have not been integral to most Jewish experience in the past. National and religious particularities are in any case more useful in rallying a people like the Israelis in a protracted war against a determined foe. In the present circumstances, we may even wonder which side is misrepresenting the truth more: Dreyfus and Leshem, by calling for pacifist or secularist gestures in order to abolish political problems, or the global democrats, for informing us that Utopia is already here. Both sides have tried to reduce politics, which properly deals with the protection of communities against their enemies, to dreams of a world without politics.

Thereby, they make it impossible to discuss national differences—even among political allies—without spiteful recrimination, since political differences are no longer tolerable among those living in either an imminent or an already established earthly paradise. Ill will and ill will alone, though variously interpreted as anti-Semitism or opposition to Jewish universalism, can cause Israeli and American interests to diverge. Indeed, it may not be ideology at all, but simply disagreement about whether Utopia is already upon us, that, in America, separates certain of Israel’s critics from certain others of its friends.

[Balaam’s Curse, by Moshe Leshem (New York: Simon and Schuster) 304 pp., $19.95]

Leave a Reply