I have showered more love on this old 1940’s farmhouse than on any person living. Certainly, I’ve spent more money on it than I care to count. But more than the house itself—an undistinguished structure made interesting only by my renovation—it’s the land I fell in love with.

The way my foot sinks into the rich, loamy soil; the five varieties of grapevines; the ancient apple tree that produces enough to make dozens of pies, gallons of applesauce, and plenty left over to satiate the birds; smoky golden Mekel pears; red quince branching like a display of Japanese ikebana; the voluble eucalyptus, the wind in its leaves like gentle laughter; and the twin cypresses, their upward curving branches like arms extended in thanksgiving.

Yet these days my love is thankless; it certainly is unrequited. Oh, it was fun in the beginning. Isn’t it always? Under the overhanging branches of the redwood grove, shielded from the afternoon sun, I used to sit on my throne—a weathered Adirondack chair—surveying my domain and thinking to myself, “Life sure is good.”

Until it wasn’t.

It started with the moles. Or were they voles? I can’t tell the difference—can you? Whatever they were, their well-planned invasion soon became my daily misery. I won’t elaborate here on the aesthetic and moral significance of my lawn, having done that in a previous column. Suffice it to say that I spent more time, exerted more effort, and spent more dinero in this department than I care to remember—and where did it get me? What did it get me? An invading army whose rapid advance is memorialized in those yellow streaks in my lawn’s green perfection, their sharp little fangs gnawing at the roots of my contentment.

I reseeded, alas to little avail, because the invaders had recently acquired a powerful ally: the weather. Four days of frost killed each and every one of my favorite plants—not the ones that were here already, but only the ones I had added to the garden and carefully nurtured. The Pandora vine, with its clusters of pink trumpets curlicued around my front porch, and its companion, a once-vigorous Wonga Wonga vine that had climbed all the way to the top of a 20-foot tree, its blossoms lighting up the canopy in a shower of gold—both gone. My Tibouchina urvilleana had survived last year’s frost, but this time it looks like a goner. The “Harlequin” honeysuckle—a new variety with a purplish cast, bright yellow stamens, and white apposite petals—that had just started its long slow climb up the fence is now stopped dead in its tracks.

As for my precious lawn, it simply stopped growing. The seeds I had carefully chosen to resist the heat of our torrid California summers—“Combat Extreme (Southern Zone)”—went dormant when the temperature dropped below 30 degrees. Four long days of it delivered what looked to be a knockout punch to my dream of a thick glossy carpet of unsullied dark green: Thin, discolored strands clung to the bare earth like the last defiant hairs on a fast-balding pate.

And then there’s the drought, which has the whole state in a panic. We have had less than ten percent of normal winter rainfall. The ranchers are living their worst nightmare: Their cattle have nothing to feed on. County officials have taken the opportunity to impose water rationing, and at this rate the reservoirs will dry by the end of the year. Reading about it in the local paper, the Press-Democrat, I took comfort in our well, and in the news that while wells throughout the region are reaching their limit, for some reason the area where I live has seen no drop in the groundwater level.

Such smug self-satisfaction is just asking for a jinx; and, sure enough, a few days later I turned on the tap and—nothing.

I avoid the well house, but the machinery within constantly calls to me, complaining. Oh, the sounds it makes! Groaning and rasping, the jet pump squeals as if in pain—as if to say, “Repair me, dammit! What are you waiting for?”

On the outside the well house is deceptively benign: It looks like a little hot-dog stand, the kind they have at the beach, with its roll-down window, silvery green siding, and white trim. But its cuteness belies its sinister interior: a concrete floor crisscrossed with cracks, spiderwebs worthy of Shelob hanging like a canopy from the ceiling, and dusty machinery whirring and whining. The UV unit, which is supposed to detoxify the water supply with its penetrating purple light, has been dead since we bought the place. After several efforts to get someone out to repair it, I had simply given up: too small a job to bother with. Well, this time they’d come out for sure.

The thought of the cost signaled the onset of a headache.

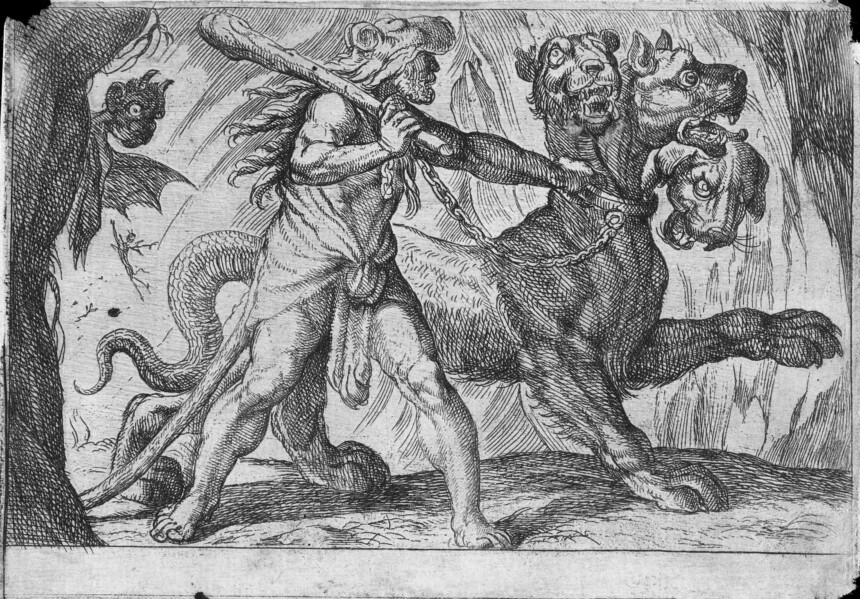

Four well repairmen later, the water pressure was restored—but the well god was not appeased. Taking an ingenious revenge, his laughter echoing hoarsely against the walls of his underground lair, he turned my water the most unappetizing color imaginable—a deep, dark orange, a cocktail of Tang and mud.

Two more repairmen later, the water started to clear. It took a week for the well god’s curse to be lifted, but his Chthonian brother, the local equivalent of Hades-Pluto, was waiting in the wings. His coming was presaged by omens and portents: The front door refused to open, a rebellion heralded by the sudden appearance of alarming cracks above the framing. This insurrection lasted a week, only to be succeeded by the revolt of the two bathroom doors, neither of which could be successfully closed. And there were those telltale cracks again, signaling my own impending crack-up as the final crisis approached.

Out here in the “unincorporated” (i.e., completely ignored) areas of Sonoma County, we don’t have none of those fancy newfangled inventions like sewer systems. You are the manager of your own private sewer, otherwise known as a leach field. It’s a system of underground perforated PVC pipes that crisscross the center of my little half-acre. At summer’s height you can see its outline in alternate rows of lush green and parched turf. These pipes connect to a series of “D-boxes”: circular concrete containers with removable lids that direct effluent downslope.

I had noticed some weeks earlier that the green stripes on the lower part of the slope had largely disappeared, but attributed it to the drought—although in the back of my mind I knew what trouble it might presage. The top part of the slope was greener than ever, and, one day as I was making my late-afternoon rounds, I looked at it closely and saw what I had feared all along.

It was a breakout. At the end of the farthest leach line, effluent had burst through to the surface, making a little trough in the soft crumbly soil.

I had never trusted this leach-field business, and constantly worried something would go wrong. A breakout of effluent can mean your leach field has failed, that the biomass which forms beneath the thin skin of the earth has thickened and saturated the ground so that it can absorb fluid no longer. The cost of installing a new system: $40-50,000.

Sure enough, it seemed that the dark spirit had finally reared up out of the earth, screaming. My fear was that, in the throes of his death agony, he would take me down with him.

A dozen phone calls and two repairmen later, the lord of the septic system granted me a reprieve: The roots of a nearby plum tree had invaded the main D-box. I also discovered that the two previous owners had done everything possible to disrupt the system’s smooth functioning. The last owner had actually put a chicken coop directly over the main D-box—a big no-no—and the heavy structure’s concrete footings had cracked the lid. The roots of the plum tree—planted dangerously close to the D-box by the owner before him—had infiltrated through this crack and got into the pipe. The perfect, albeit unconscious, collaboration of idiots across a stretch of years had brought me to my present predicament—and cost me 1,200 bucks.

Worse, it cost me my plum tree, which had never yielded a single fruit, yet blossomed each spring so magnificently that its sterility hardly mattered. It had to go, unless I wanted to invite another root invasion, and its death brought on fresh disasters. As I was breaking up the branches in my hands, one of them lashed out at me, stabbing me in the eye, as if to say, I’m not going down without a fight!

Well, I thought as I walked down to the house to inspect the damage, at least the leach field is fixed. It was then that I saw it out of the corner of my damaged eye: at the bottom of the hill, where the buried leach line is shallowest, a dollop of water pulsing out of the soil . . .

Why has the earth—this place—turned against me?

How can I have a “sense of place” if the land, the house, the weather, the grass, the water all rise in rebellion at my dominion over them, laughing in my face even as they seek to overthrow me?

Leave a Reply