The George Floyd riots of 2020 left scores dead and caused billions of dollars in property damage. A clangorous bonfire of physical and political upheaval transformed the national landscape overnight. Both Democrats and Republicans committed themselves to enacting reforms to soften our criminal justice and policing systems under the banner of removing the taint of an alleged history of racial oppression. The largest and most established companies in America vowed to give preferential treatment to “people of color” in hiring.

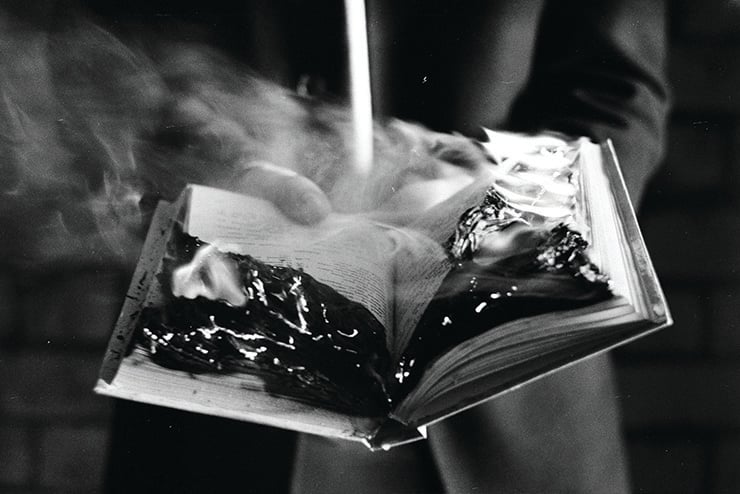

Politically, 2020 was a kind of “Year Zero” for America. The Khmer Rouge introduced that term to the political lexicon in 1975 upon their takeover of Cambodia. Drawing inspiration from the Jacobins, Year Zero signified for Pol Pot’s revolutionary forces the complete cultural reset of society. To that end, they burned books to erase memories of the past. They even persecuted people who wore glasses on the theory that they were probably regular readers and, therefore, in possession of knowledge about how things were in the before times.

We are not—and, we can hope, never will be—quite at Khmer Rouge levels of cultural revolution. However, one understudied aspect of our Year Zero moment was the acceleration of “sensitivity editing” in the publishing industry. “Sensitivity edits are a publisher’s or editor’s insurance to protect reputation and ward off profit loss,” Writer’s Digest explains. “Sensitivity readers” pore over texts for transgressions big and small and recommend sensitivity edits. Their job is to “cancel-proof” writing by preemptively combing it for offenses against the prevailing pieties about race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so on. Instead of burning the whole book, expert philistines edit or expunge passages and words deemed problematic.

Sanitizing books before they go to print may sound harmless enough or even just profoundly silly. But what happens when previously published works—even classics—come under such scrutiny? That’s what occurred after Floyd’s death.

“The use of sensitivity readers, say people in the industry, has increased since 2020, prompted by calls for more institutional inclusion and diversity following the death of George Floyd,” the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported in 2023. Los Angeles-based sensitivity reader Patrice Williams Marks told AFP the same thing. Since 2020, Williams said, authors and publishers have “become more conscious of the lens that they’re looking through.”

“Conscious” is one way to put it. Cowardly and cretinous would be more accurate terms. Among the victims of this craven dumbing down were classic works of fiction by Agatha Christie, Ian Fleming, and Roald Dahl.

Last year, The Telegraph revealed that starting in 2020, HarperCollins had scrubbed Christie’s novels of references sensitivity readers deemed out of step with the times. “Digital versions of new editions seen by The Telegraph include scores of changes to texts written from 1920 to 1976, stripping them of numerous passages containing descriptions, insults or references to ethnicity, particularly for characters Christie’s protagonists encounter outside the UK,” the paper reported.

The term “Oriental” has been struck. In one story, a black servant who grins to indicate that he understands the need to stay silent is no longer described as black nor grinning; he is now a deracinated, “nodding” creature. Likewise, references to “Nubian people” have been removed from Christie’s 1937 novel Death on the Nile. The Nubians are an ancient ethnic group originating from a people who have inhabited Egypt since time immemorial. Unfortunately, they did not survive the moral panic of the current age.

Fleming’s James Bond novels received a similar treatment at the hands of sensitivity readers. On the eve of the spy series’ 70th anniversary, The Telegraph revealed that “Ian Fleming Publications Ltd, the company that owns the literary rights to the author’s work, commissioned a review by sensitivity readers of the classic texts under its control.” The racial descriptions of criminals, doctors, immigration officers, military units, and butlers are completely dropped in some cases. Some depictions of black people have been changed or reworked. In one passage, Fleming describes a man’s accent as “straight Harlem-Deep South with a lot of New York thrown in.” It has been completely excised from the text.

Puffin Books, an imprint of Penguin Books, has worked to sterilize Dahl’s classic children’s novels, including James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Now, first-time readers of these lobotomized editions will not know Oompa-Loompas as “small men,” for that insensitively assumes their gender, but as “small people.” Augustus Gloop is no longer “fat,” but “enormous.”

More than 70 changes were made to James and the Giant Peach. Benign references to skin color have been erased. The Cloud-Men who live high above the earth and hold the power to command the weather are now genderless, bland Cloud-People. Whole passages that survived outright removal have been sterilized. In the original text, this description of the lives of Cloud-Men appears:

There were caves everywhere running into the cloud, and at the entrances to the caves the Cloud-Men’s wives were crouching over little stoves with frying-pans in their hands, frying snowballs for their husbands’ suppers.

Now, that passage appears in the 2023 text in the following denatured form:

There were houses everywhere running into the cloud.

It might have been better to completely cut this passage altogether than amputate its arms and legs and leave it dismembered on the page.

In Matilda, Dahl describes how literature has the power to transport us to places we’ve never been through the power of imagination. “She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad,” he wrote. “She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling.”

After the sensitivity geniuses have done their work, that passage reads: “She went to nineteenth-century estates with Jane Austen. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and California with John Steinbeck.”

Kipling is gone, and with him, the thrill of adventure. Steinbeck seems as arbitrary as a name hauled out of a hat, and Austen never ventured far from parsonages, country houses, genteel lodgings, and the home in general. That’s fine. Austen is a master at her craft. But Matilda is an abused and neglected girl who wants to escape from home. Reading was obviously Matilda’s way of escaping without leaving the living room. If the sensitivity readers were literate, they would have understood that their edits, no doubt aimed at fighting the patriarchy and other unnamed evils, instead bowdlerize Dahl’s meaning and intention beyond recognition.

Editing texts to bring them into line with the tastes of the day isn’t a new phenomenon. Indeed, the term “bowdlerization” comes from Thomas Bowdler’s 1818 revisions of William Shakespeare’s plays. Like the sensitivity readers of our time, Bowdler took it upon himself to clip the Bard’s wings and dumb down his prose, but his object was to make Shakespeare’s content more suitable for children.

There’s something much more sinister about today’s industrial-scale effort to extirpate all offense. William Bowlder did not have groups like Inclusive Minds at his disposal. That’s the organization advising the revisions for Puffin and the Roald Dahl Story Company.

Inclusive Minds employs so-called “authenticity advocates,” formerly known as “inclusion ambassadors,” who use their “lived experiences” to help authors and publishers create “inclusive books.” According to Inclusive Minds, these people are distinct from sensitivity readers, and their job is to “provide valuable input when it comes to reviewing language that can be damaging and perpetuate harmful stereotypes.” Sensitivity readers come later in this division of labor. Here is the mission statement of Inclusive Minds:

We believe in breaking down barriers and challenging stereotypes to ensure that every child can access and enjoy great books that are representative of our diverse society. Every child should be able to find themselves in books, so mainstream books need to represent every child.

“Great books,” however, are not supposed to merely serve as mirrors for us and whatever fancies and fashions prevail in our current society. They are windows into other times, other worlds, other lives. This sensitivity project flattens them. The effort to make these works more “diverse” strips them of everything that make them unique and homogenizes them into bland items devoid of color or flavor. They are like the dystopian censors of Lois Lowry’s The Giver, who attempt to purge all pain and suffering from society through “Sameness,” eliminating all depth from life—all music, all color, all notions of love and hate.

The result is Year Zero, a society perfectly equal and perfectly inhuman. One suspects the sensitivity industry would have us live there, too. ◆

Leave a Reply