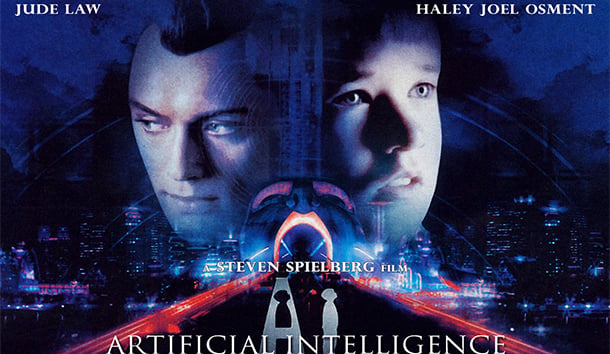

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Produced by DreamWorks and Warner Bros.

Directed by Steven Spielberg

Screenplay by Ian Watson, based on a story by Brian Aldiss Released by Warner Bros.

Sexy Beast

Produced by Channel Four Films and Recorded Pictures Company

Directed by Jonathan Glazer

Screenplay by Louis Mellis and David Scinto

Released by Fox Searchlight Pictures

A.I., Steven Spielberg’s fantasy about a robotic future, should stand as an object lesson to directors: Any film that includes Fred Astaire on its soundtrack had better be light on its feet. Astaire’s eloquent walk-on here reveals A. J. to be shod in concrete. Forty minutes into the narrative, we meet Gigolo joe (Jude Law looking like a rejected Cary Grant effigy from Madame Tussaud’s). Joe is an android programmed to lift the spirits of lonely women. But when this mechanical loverboy plays Astaire’s peerless rendition of “Cheek to Cheek” on his built-in circuitry, the effect is sadly deflating. He inadvertently confirms what we’ve already concluded: A.I. is to Astaire as lead is to mercury. It ain’t got an ounce of dance in it.

A.I. is not bad in the usual Hollywood way. It’s been made with care by people who want to engage their audience seriously. Its cinematography is exquisite, and its visualization of the future is often compelling. Unlike most big-budget films today, its special effects serve its story rather than overwhelm it. The acting is excellent throughout, especially that of Haley Joel Osment, the boy who gave The Sixth Sense its uncanny intensity. Even William Hurt, who has been sleepwalking through his recent performances, takes fire in the role of a well-intentioned but shortsighted Frankensteinian scientist who insists on creating robots capable of genuine feelings. If they can be made to experience love, he reasons, they’ll have the “mechanism” by which they will develop a subconscious. (Perhaps he means soul.)

There are even moments in which questions of faith, morals, and mortality are raised far more sharply than other mainstream entertainers would dare. But Spielberg, perhaps under the influence of the late Stanley Kubrick (who had originally planned to make this film), has picked up the wrong end of his narrative’s premise—and he never lets go. His grip is as firmly literal as it is aesthetically fatal.

Working from Brian Aldiss’s story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long” and a preliminary script developed by Kubrick, Spielberg tells the tale of David, a robotic replica of an 11-year-old boy programmed to love whoever “adopts” him. The trouble begins when he’s taken into the home of a couple as a substitute for their biological son, Martin, who is suffering from some unspecified malady that has rendered him indefinitely comatose. David does his job too well. The mother becomes completely attached to him. Understandably, when Martin recovers and comes home, he sees the robot boy as his rival. Programmed for good behavior and tireless decency, David would prove an unendurable trial for any ordinary child, let alone a sickly “sibling” recently back from the hospital. Soon, Martin is plotting David’s downfall. Instinctively taking advantage of the robot’s innocence, he lures his mechanical brother into activities staged to seem willfully malevolent. The parents feel they have ho choice. They must get rid of David for the safety of their real child.

Before David finds himself abandoned, however, he has overheard his mother read Pinocchio to his flesh-and-blood “sibling.” He reasons that, if he can become a real boy, his mother will love him once more and take him back into her home. And so he begins to search for the Blue Fairy who rescued Pinocchio from his wooden fate. David’s quest takes him (and us) on a swift tour of the narrative’s future world. We discover that the greenhouse effect has become a fait accompli. Coastal cities are underwater, and population growth has never been more menacing. Governments of the developed world have made pregnancy without special licensing illegal. The affluent live comfortably by virtue of robots who do the scut work of society. Meanwhile, what’s left of the shortchanged working class seethes with resentment at having been replaced in the labor market by “thinking” metal. The workers of the world are now united in their hatred of robots. They celebrate organic life by kidnapping their mechanical competitors and sadistically destroying them in demolition-derby-style events. The hapless robots are shot from cannons, set aflame, and melted with industrial corrosives. Programmed for obedience to the end, the rational mechanisms offer little resistance to the rabid humans beyond meekly pleading that their sensory circuits be disconnected before the wreckage begins.

Despite witnessing this all-too-human beastliness and nearly becoming one of its victims, David persists in his quest to join the ranks of flesh and blood. He’s willing to do whatever it takes to win back his “mother’s” love. We’re encouraged to believe that he’s more genuinely human than the humans. This is the film’s moral, and it’s a real sentimental clunker. While it may be pretty to think so, genuine humanity does not reside in the kind of automatic goodness David exhibits. Isn’t this Carlo Collodi’s point in the original Pinocchio? The puppet boy becomes a “real” boy by overcoming his innocent susceptibility to being misled and then decisively putting his father’s welfare before his own. Isn’t this the moral challenge we all face if we want to become humanly worthwhile? It’s always a struggle to overcome, however partially and provisionally, our innate selfishness. Spielberg has put the cart before the horse, goodness before the struggle. David is a liberal’s sentimental dream. As such, he’s too inhumanly sweet to serve as a serious reproach to our admittedly sinful natures.

Filmmaking is Spielberg’s talent, not philosophizing. As usual, he’s created a correct thinker’s Manichean universe populated by the inherently good (this time the robots) and the irredeemably nasty (the humans). Worse, he seems to be playing with a notion that Kubrick is reported to have entertained: that, ultimately, humanity will be subsumed and redeemed by the artificial higher intelligence of a computerized robot culture. In what seems a desperate coda, Spielberg introduces—as a deus ex machina—a band of sleek, jointless mechanical beings to lend their gleaming hands to the proceedings. They look suspiciously like the benevolent aliens who came to enlighten us all at the end of his Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Spielberg, bless him, always insists on consoling us with as hopeful an ending as he can muster. Personally, I found his conclusion ghoulish—literally so —for reasons I shouldn’t reveal here.

For all its visual beauty and technical imagination, A.I. is peculiarly lacking in resonance. It has some very affecting, very intense moments, but overall it falls flat. Spielberg has warped the literary nature of Aldiss’s original story (as Kubrick may have as well). He has chosen to make literal what was meant to be a metaphorical premise. The robot in Aldiss’s story functions as a reproach to human selfishness; its fate as a mechanical being is irrelevant. By contrast, Spielberg’s sole focus is the pathos of his boy robot as a robot. He insists on realistically rendering David’s artificiality. To take just one of innumerable instances, he makes a big deal of David at the dinner table. Because he cannot ingest food, David does a pantomime in order to keep his adoptive parents company, lifting an empty fork to his mouth and making chewing and swallowing motions. One evening, however, he decides to eat for real. He swallows a mouthful of creamed spinach and shorts out his circuitry, causing the synthetic flesh of his face to sag horribly. Although visually clever, this emphasis on David’s mechanical being undermines his symbolic function. Instead of a literary tactic meant to stimulate reflection on what it means to be human, he becomes something far less interesting: a bit of Popular Mechanics speculation about whether or not robots have a legitimate future as our descendants. (I don’t know about you, but my idea of progeny doesn’t run to hard drives and software, even if they are morally programmed for unwavering decency.) By making Aldiss’s original premise the literal point rather than the metaphor of his narrative, Spielberg has fallen into an error similar to the one to which his human characters succumb. He’s preferred the seeming security of a device to the unpredictable challenge of life. Still, his film is provocative and worth seeing. But it’s decidedly not for kids. It portrays loss and mortality far too starkly for youngsters under 14.

Sexy Beast is a small British film that has no difficulty with its literary metaphors. They tumble into the plot as playfully and unapologetically as the six-foot boulder that whizzes past our protagonist. Gal Dove (Ray Winstone), just a minute after we meet him. This, of course, is itself a great big metaphor, but it’s not nearly as big as the one played by Ben Kingsley as Don Logan, Gal’s worst nightmare.

The film’s opening shot reveals Gal sunning his oiled and beefy body by the exquisitely tiled pool of his hillside house on the Costa del Sol in Spain. He is a former London criminal who has retired to the good life with an erstwhile porn star for his faithful and devoted wife. He has what seems to be an aging, softening thug’s dream. The first words out of his mouth, however, suggest otherwise. “Bloody hell,” he says to himself, lying there in his sun-yellow, ridiculously brief bathing tights. “I’m roasting.” The next scene is shot through the flickering flames of a barbecue grill, turning Gal’s fleshy face into a crimson jack-o’-lantern. Although he resists the knowledge, he’s in a hell of his own making. Logan will clarify matters. When this live depth charge from his criminal past shows up, the atmosphere turns positively gelid with fear. Gal and his wife move about their airy house in slow motion as though they were 20 leagues under a sea mined with terror. Gal’s acquaintance with Greek myth may be slight, but he knows his nemesis when he meets him.

The fun of this film is in the performances of Winstone and Kingsley. They’re enjoying themselves immensely, and this energizes the narrative. Kingsley has shaved his head so it looks like a missile tip atop his square-shouldered, ramrod back. This man means business. He doesn’t walk; he marches. He doesn’t talk; he barks. He doesn’t ask; he commands. Kingsley has contrived to transform the large, soft eyes that served him so eloquently as Ghandi. Here, they have become two burning coals that flare into the faces of everyone he meets, searing away any last remnant of pretense or falsity. This is a man who calls everyone’s bluff He’s come to bring Gal back to London to assist in a heist. Why he so urgently needs Gal is never explained—which is puzzling, since Winstone looks like nothing more than a criminal journeyman. He may once have had some muscle to recommend him, but at this point in his life, this asset has sagged shamefully.

You can see why Gal wants no part of Logan’s assignment. It’s written in his fleshiness. Winstone makes a slightly depressive pin cushion of Gal, absorbing the barbs the implacable Logan hurls at him, one after another. “It’s like this,” Gal begins again and again, trying to explain his current preference for the quiet life. But Logan won’t let him get the traitorous words out. “Like whot; like whot,” he interrupts derisively in his staccato cockney. Finally Winstone can only whimper, “I’d be useless,” to which Logan retorts, “You’re disgusting.”

As the one-sided verbal sparring goes on, we come to realize Gal’s life is infected with Logan; he was contaminated many years ago as a member of the British underclass, and he’s never purged this sexy beast from his system. The question the film raises is whether or not he ever will. As metaphors go, Kingsley and Winstone are superbly eloquent.

Leave a Reply