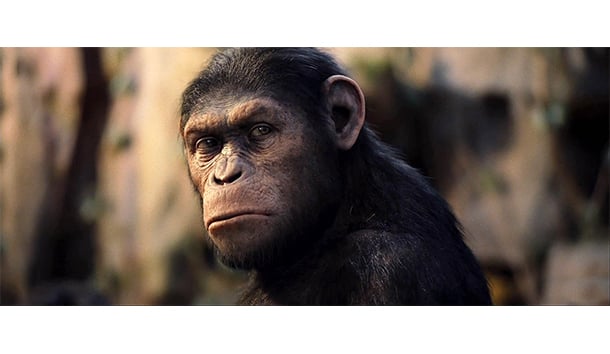

Planet of the Apes

Produced and distributed by 20th Century Fox

Directed by Tim Burton

Screenplay by William Broyles, Jr., from Pierre Boulle’s novel

Ghost World

Produced by Capitol Films, United Artists, and John Malkovich

Directed by Terry Zwigoff

Screenplay by Daniel Clowes with Terry Zwigoff

Released by MGM-UA

The 1968 film Planet of the Apes was based on French novelist Pierre Boulle’s 1963 Swiftian satire. On screen, the adaptation became a wildly popular and, not coincidentally, satirically tamer narrative.

The movie resembles an expanded Twilight Zone episode. That’s not surprising: Rod Serling worked on the screenplay. Charlton Heston plays an astronaut whose rocket takes a wrong turn and somehow passes through the spacetime continuum to crash on Earth in the distant future. There, he discovers that apes have gained control of the planet and made humans their slaves. Once established, the conceit of a species-dominance switch enabled the movie to deploy a series of arch parallels to the “real world” issues of the late 60’s, the kind of groaners that Serling could never resist: man’s inhumanity to man, fractious race relations, small-minded xenophobia, the dangers of high-tech weaponry, etc. All of this was allegorized through ape makeup. Where, the film demanded to know, was the line between civilization and savagery?

Planet of the Apes became a huge success, spawning four sequels and a television serial. Why? It’s the Star Trek phenomenon. Films like these inhabit the sententious end of the sci-fi spectrum. They appeal to Americans’ two basic needs: moral uplift and bargain savings. You can watch them for fun and feel edified at the same time—an irresistible two-for-one deal.

Tim Burton’s new Planet of the Apes wants to walk the same profitable moral line while being self-consciously cool. This two-track strategy doesn’t work. Burton ironizes his narrative until he loses all control of it. Serling believed in the moral purpose of his project; Burton does not. Lame as they were, Serling’s anachronistic references to contemporary concerns were meant to surprise us into moral reflection; Burton’s merely invite us to indulge in superior snickering. Consider what passes for wit in Burton’s film. He has one sensitive ape—played with simian delicacy by Helena Bonham Carter—plead for human rights, only to be rebuffed with the old racist canard: “How,” her father asks impatiently, “can you tell one from the other?” When an orangutan who sells humans into slavery finds himself cornered by armed humans, he whimpers Rodney King-style, “Can’t we all just get along?” Later, a fascist chimp declares, “Extremism in the defense of apes is no vice.” These jokey references make it impossible for the audience to suspend disbelief. When the film tries to shift into a rousing adventure mode, we’re left behind. No matter how ferociously staged, the battles between the species leave us unmoved. What can be at stake in a story this campy?

Still, there are things to enjoy here. Burton’s narrative skills may be weak, but he knows how to hypnotize us visually. The apes’ tree-house villages look absolutely convincing. The costumes and makeup are flawless. We may not believe the story, but it’s difficult to doubt that we are in the presence of thinking, talking apes. There is only one distracting lapse in verisimilitude: Carter wears mascara and lipstick over her ape mask. I suppose this was meant to give her feminine appeal so that we wouldn’t be entirely disconcerted when she makes eyes at Mark Wahlberg, who plays the Heston role. No doubt, Peter Singer would approve of such interspecies romance.

As the fascist chimpanzee General Thade, Tim Roth does best. He plays his role as one extended acting exercise, doing a chimp version of Richard III. As he sidles stoopingly into their presence, the other apes cringe, their eyes widening fearfully. He sniffs at them stertorously, pawing at their shoulders with ambiguous primate gestures. Does he mean to preen the fleas from their fur or to throttle them? Roth is menace incarnate. When he’s on screen, you fully believe in his danger. He’s the one steel beam, however twisted, in an otherwise papiermâché construction.

Paul Giamatti is also exceptional as the orangutan slave trader, and he gets to deliver the one genuinely comic line in the film. As he strikes a deal to sell a three-year-old girl to an ape family, he warns them to get rid of the pet before it reaches puberty: “The one thing you don’t want in your house is a human teenager.”

As if to prove the monkey right, Terry Zwigoff, in his ingenious adaptation of Daniel Clowes’ graphic novel, Ghost Story, gives us teenagers in malodorous bloom.

We first meet the 17-year-old principals, Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johannson), at their high-school graduation, each flaunting a disdainfully curled lip at the proceedings. They practically gag when the valedictorian announces that “high school is like the training wheels for the bicycle of real life.” Unlike this cheerful optimist, they don’t see anything particularly real ahead of them. As a result, they’re disaffected, sullen, aimless, and randomly mischievous. In another, saner age, their adolescent nihilism would be insufferable—and Zwigoff acknowledges this. He doesn’t take the conventional route of turning these girls into soulful teens martyred by insensitive adults. He insists, however, that their response to contemporary culture is not entirely unwarranted. These girls may not be geniuses, but they’re perceptive enough to recognize the emptiness of the life that America has prepared for them. They want out but find themselves arrested in a state of frozen petulance. They can’t quite figure out where to go or what to do.

The studio thought police must have been asleep at the switch during the making of this bracingly acerbic film. Zwigoff openly mocks a gamut of contemporary heroes—including pro-abortion lobbyists and hypocritical diversity mongerers—by rigorously limiting the film’s point of view. We see the world entirely through the eyes of Enid and Rebecca. The view is chastening, especially since they are far more innocent than they would dare admit.

The friends wander about their California suburb’s strip malls, trucking their way along the sidewalks in clunky platform shoes and laughably abbreviated skirts. Their getups unflatteringly accentuate their wide hips and slouched shoulders, making them look like wanton hoydens. Of course, they’re nothing of the kind. Sure, they talk tough about sex, but their behavior reveals their inexperience. They can’t seem to get dates; for romantic excitement, they’re reduced to girlishly teasing a young man working the counter at a convenience store. Rather than the worldly seductresses they pretend to be, these girls are undoubtedly still virgins. In another time, their intact state might have been grounds for personal confidence and moral pride—but not in modern America, where pop culture relentlessly schools the young to believe that something’s wrong if you’re not sexually rampant by 14. To avoid embarrassment, Enid and Rebecca have no choice. They must pretend to be well experienced in debauchery. Enid’s mischievous visit to the town’s adult bookstore gives the lie to her pose, however. After watching men furtively thumb porn magazines for a minute or so, she bursts out laughing. It’s too ridiculous, and she’s not afraid to let the gentlemen know that she thinks they are contemptible.

Zwigoff never ridicules the girls, treating them instead with gentle, appreciative humor. He reserves his scorn for the forces within our society that exploit normal adolescent confusion, especially the sordid pop-culture industry and the ideologues of various leftist agendas.

For instance, Enid’s art teacher (Illeana Douglas) begins her course by showing her own video production featuring a doll being dismembered, its limbs cast one by one into a bloody toilet bowl. At its conclusion, she tells her students that she wanted to give them “an idea of what it’s like to be in my specific skin.” She’s convinced that art of genuine merit must fuse aesthetic expression with personal confession. What she’s confessing is, of course, all too obvious. A few meetings later, a go-getter coed follows her lead, exhibiting a sculpture she’s constructed of coat hangers, cannily explaining that it “speaks to a woman’s right to choose.” This, clearly, is a girl who knows how to play the game. Predictably, the teacher can’t restrain her enthusiasm for this marriage of aesthetics and activism. Enid, however, slumps in her seat, her face glum with misgivings. She may lack the resources to articulate her dissent from America’s prevailing abortion-rights ethos, but she intuitively recoils at the grotesque spectacle of adults encouraging the young to support the murder of inconvenient babies. It does, after all, cut rather closely to an already alienated adolescent’s bone.

The best element in the narrative is Enid’s friendship with Seymour (the always reliable Steve Buscemi), a forty-something connoisseur of blues and ragtime. She meets him at a garage sale, where he’s selling 78 LPs of his favorite artists. Although he’s an unprepossessing fellow, he fascinates her. It’s easy to see why: He’s completely out of step with the contemporary culture that has failed her so miserably. He decorates his room with 1940’s film posters, book covers, and magazine advertisements. As Enid says, “He’s such a clueless dork, he’s almost cool.”

Seymour, as his name implies, helps Enid see more. He reveals the increasingly ghostly world of an earlier America that modern commercial and political interests have tried to erase. In perhaps the film’s most daring assault on today’s programmed attitudes, Enid discovers in Seymour’s apartment an advertisement from the 1930’s restaurant chain. Coon’s Chicken Inns. It features a caricature of a moonfaced negro wearing a bellman’s cap. He grins from ear to ear, winking as he offers the observer country-fried poultry. Startled at what she takes to be flagrant racism, Enid challenges Seymour. He explains that such imagery was not generally thought offensive in the early 20th century. Now, he sarcastically continues, the company has renamed itself Cook’s Chicken, deferring to today’s more tender sensibilities. Enid asks wonderingly, “Are you saying things were better back then?” Admitting that he thinks race relations are probably better today, he goes on to explain that such issues are complicated. “People still hate one another; they just know how to hide it better.” Enid senses she’s onto something and borrows the picture to show her art class. The other students predictably greet it with the shocked dismay expected of them. Enid then unmasks their reflexive hypocrisy. Her “found art,” she argues, reveals the hidden racism in our midst.

This is, of course, tricky ground. I take Zwigoff to mean that Americans have been hectored into conforming to a variety of institutional hypocrisies concerning not only race but supposed sexual discrimination, cultural differences, religious beliefs, and censorship—to name just a few. Consider how “diversity” has become the password of enlightenment among business executives who routinely spend their weekends playing golf on all white courses. It’s a commonplace today that the racism African-Americans find most irksome is the kind that’s veiled behind the seeming acceptance of polite white folks. But more than this, how many among the college-educated middle class are openly willing to question “a woman’s right to choose”? How many will publicly risk saying that AIDS is a disease almost always contracted through extravagantly perverse behavior? Many have decided, prudently or spinelessly, to avoid the possible consequences of crossing the lines set down by well-heeled, powerful interest groups. The older America might have been rougher and filled with all manner of intolerance, but at least people knew where they stood.

The Coon’s Chicken ad propels this remarkable film to a denouement that is at once hilarious, sad, and troubling. Unlike Burton’s Planet of the Apes with its ersatz moralizing, Zwigoffs film raises a real question of conscience: Why do we so easily make peace with our civic savageries?

Leave a Reply