There is an old cliche that no man is a hero to his valet. Some have been tempted to reply that it depends on the man, but I think it depends, rather, on the valet. To an observant eye, the world is peopled by ordinary men making strenuous, even heroic efforts to get through the day without cheating their customers or betraying their wives. Even everyday objects may interest a poet, if his imagination is strong enough, because there is nothing so banal that, if held up to inspection, it cannot illuminate the world. We cannot always be mooning over skylarks and Chinese emperors. For a really strong imagination a louse will do as well as a nightingale.

A man might write a great novel about life here in Rockford, so long as he is really willing to live his life fully in such a place. In the case of Rockford, perhaps an editorial will suffice, but even here the most ordinary object is worth a moment of reflection. A telephone book, for example, is a strange thing, if you will take the time to think about it. In very small towns, such things are hardly necessary, since everybody knows everyone else, and if a stranger comes to a Wisconsin hamlet looking for an Anderson, he may find out that everyone in town who is not a Larson is an Anderson. Even small town Yellow Pages are uninformative, unless it is an area that attracts tourists, because the locals already know where to go for everything, and it is not as if they had a great deal of choice.

In larger cities, even such minuscular large cities as Rockford, the telephone books are less coherent but more informative. Apart from the prevalence of Swedish, German, and Italian names, not too much could be concluded from an examination of the Rockford directory. The Yellow Pages, on the other hand, are filled with lures and hooks and advertising slogans designed to beguile the unwary into thinking that there might really be a good restaurant, an interesting store, or some place to go in the evening. We usually return from such expeditions defeated, but this does not prevent us from opening the telephone book the next time we are playing Don Quixote, and once again it will be the inedible meal that we find rather than the impossible dream.

When community is gone, there is still the telephone book that connects the hundred thousand telephones of Rockford in a conversation made up of wrong numbers, burial plot solicitations, final warnings, and restaurant reservations. Peggy Noonan’s thousand points of light was only a flicker compared with the blaze created by the vast neural network of a hundred million American telephones. Our place in the world is defined by the area code and number that expose us to any discount broker or insurance salesman with a finger, and if we think we can escape by paying for an unlisted number, there are unscrupulous people whose business it is to sell unlisted numbers, and there is no protection against the lawn service or pollster with computerized dialing. “If you would like more information, press one. If you would like to place an order, press two.” And if you would like to keep these jerks off your back, get their name and number and start calling them up at three o’clock in tire morning.

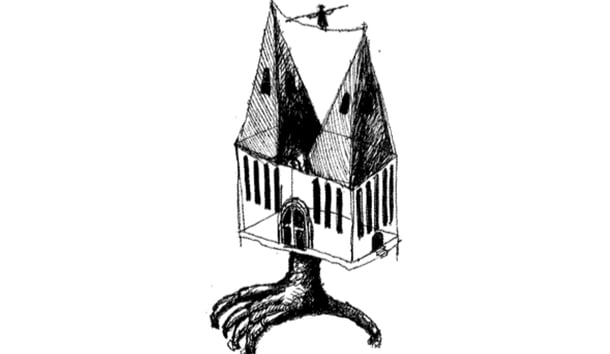

The telephone directory is the address book of the artificial community of commerce, and along with city directories and mailing lists, it is the sacred scripture of our national religion. It is, therefore, not merely offensive when evangelical Christians presume to put out their own directory—here in Rockford it is called The Shepherd’s Guide—it is blasphemous. Most of the businesses listed in The Shepherd’s Guide have not been content simply to list themselves, but they have gone so far as to sign a statement of faith, stipulating that “I have received Jesus Christ as my personal Savior” and pledging “to hold the highest Biblical code of ethics in my business transactions.”

The local newspaper has been uncharacteristically civil in reporting on this Guide, but at least one businessman wrote in to say that the project violated the first rule of American business, which is to keep religion out. I do not actually recall hearing that rule pronounced at any of the three Rotary meetings I have attended, but perhaps the Rotarians do not divulge their mysteries to the profane. Some groups certainly do act as if they do not separate religion from business. Catholic schools and churches, for example, sell advertising to Catholic businessmen, and in some cases the church urges parishioners to give their trade to the Catholic businessmen who have taken out advertising. My Lutheran friends also seem to know where every Lutheran appliance store or carpet shop is located, and my Jewish friends are just as well-informed. Blacks are always issuing appeals to patronize black-owned businesses, and here in Rockford blacks came out with their own Yellow Pages just a few weeks before the Evangelicals did. Obviously, many of us like to shop where we know and are known by people, and such parochialism can only be regarded as a sin in the eyes of those who either have no religion or who find such a pretense useful.

The non-Christian businessman’s denunciation is only one small indication that we do not live in a Christian country or even a God-fearing country. Jefferson’s private opinion that there was a wall of separation between church and state has been turned into a constitutional rule establishing an iron curtain that confines religious activity to the church and home. If only some of Jefferson’s other opinions could achieve the status of law, A few weeks ago the Chicago Tribune published a typically idiotic piece by some professor or other, saying he believed Jefferson would today be on the side of those who were trying to keep religion out of public life.

Oh, really? This is the same Jefferson who feared and loathed the Supreme Court as an uncontrolled agent of tyranny back in the benign days of John Marshall, whom he would have impeached for his violation of states’ rights, and yet now he would be supporting the federal courts in their drive to subordinate all local institutions to the power of the government in Washington? I am convinced that the vast majority of Constitutional lawyers and “political scientists” cannot read English, much less understand the Constitution.

But why go on? Real Americans already know that the federal government has declared war on religion and that not even the fig leaf of the 14th Amendment—passed illegally at gun point—can sanction court rulings against creches in public squares, prayer in schools, and the parents’ right to prevent their daughter from murdering their grandchild. We know all this or ought to, but what can we do, poor, helpless subjects of this vast state, to resist, or if not to resist at least to survive and thrive without collaborating with our oppressors?

For a variety of reasons, we must pay our taxes. In the first place, they will come and get us if we do not, and it is a good deal harder to be good parents and faithful friends when we are deprived of our property and sent to federal prison. More importantly. Christians are commanded to “render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s,” and to the extent we continue to enjoy the protection of the police, sue in the courts for damages, and drive on the roads, we are obliged to obey the laws and pay our taxes. If a man were to sell up and move into the wilderness, he might be morally justified in repudiating the government, but they will still hunt him down and shoot him or his family for resisting arrest.

If few of us are ready to play the part of Randy Weaver, our situation is not hopeless, and projects like The Shepherd’s Guide point the way. We cannot always shop with Lutherans or Baptists or Catholics, but we can choose to keep our money out of the hands of unbelievers and persecutors. In fact. The Shepherd’s Guide is itself a good deal too evangelical for my taste. While it does list Catholic churches, I cannot seem to find any obviously Catholic or Episcopalian businesses. There are surprisingly few Lutherans in the book, and under insurance I sec neither the Lutheran Brotherhood nor the Aid Association for Lutherans. Of course, it is their business, and if they do not want mine, they are doing the right thing.

I should be the last man to object to any of the most provincial or more parochial conspiracies, but perhaps it is time for a broader front. Various religious groups have over the years recommended specific boycotts against corporations that purveyed pornography or supported infanticide, but it is time to up the ante, so to speak, and to declare economic war against all the corporations that are attacking Christendom. If some Christian coalition would actually do the work and draw up a reliable index of prohibited businesses, I would cheerfully take the pledge to abstain. In the meantime, we might think in terms of a few obvious categories.

Why not begin by refusing to watch television shows or go to films whose producers and stars are flagrantly opposed to every decency? Excepting for a moment the cases of real artists like Martin Scorsese, who continues to play the part of the perpetual ex-Catholic, why not simply refuse to cut Hollywood any slack? If Tom Hanks wants to promote homosexuality, it is not enough not to go see Philadelphia—he did not expect us to. But if we refuse to buy tickets to Forrest Gump or even to rent the video, then he and his masters will begin to get the picture. The same treatment ought to be given everyone who does an AIDS benefit concert (e.g., Kathy Mattea) or sports an AIDS ribbon at an awards ceremony. At least we can still watch Clint Eastwood and Gene Hackman.

The same principle applies to studios and producers and stars involved with obviously blasphemous films; companies that use nuns, priests, and heavenly voices in their commercials; publishers that put out books like Passover Plot; and writers who give interviews to Playboy. Why be generous? I avoid movies with Barbara Streisand, because she is ugly, and Eddie Murphy, because he is foul-mouthed in his comedy routines. A year or two ago I was about to do a television spot on the Constitution, but as soon as I found out it was being produced by Time-Warner—the producers of “Cop-Killer,” I withdrew. I could go on, “but the task of filling up the blanks I’d rather leave to you . . . “

There are more issues than blasphemy and immorality to concern morally responsible consumers. Many large companies give money to the baby-killers at Planned Parenthood and NOW, and in recent years this grisly index has included Pillsbury, Levi Strauss, General Mills, and American Express. The next time you are eating the processed food products at the Olive Garden, you might consider that you are destroying more than your taste buds and digestion.

Some major corporations have signed anti-white affirmative action agreements with the NAACP or Jesse Jackson. If it is only because they feel threatened, let them begin to understand that majorities can threaten as well as minorities. At one time, that list included the many popular soft drink companies and many fast-food chains. My solution is to drink iced tea and stop at the diner. Down in Georgia, the Holiday Inn and other chain motels are refusing to fly the Georgia state flag, because it includes the Stars and Bars. What, you say your great-grandfather enlisted in the Grand Army of the Republic? In that case, he probably would not want to see the flag of his enemies dishonored. By the golden rule of nationalism, if you want your own nation, culture, and religion respected, you must acknowledge the respect that is due to others. I prefer not to buy my groceries either from Ku-Kluxers or from those who fund their black counterparts in the NAACP.

Since some boycotts are illegal or, at the very least, invitations to lawsuits, I am not recommending any specific action. However, this is a case where we can take instruction from the leftists who refuse to invest in companies that trade with South Africa or pollute the environment. My advice is to spend your money exactly as if you are voting. If you do not like a company’s corporate policies, then why in God’s name are you subsidizing what you believe to be evil? Because of the Georgia flag controversy, I have forbidden my children to drink Coca-Cola, and since Pepsi is even more disgusting than Coke, they drink root beer, preferably not one of the national brands, because if men and women really believe in restoring local community, they ought to begin by shopping with their neighbors instead of with the national chains whose business it is to drive their neighbors into bankruptcy.

Back in McClellanville, we tried to buy the better part of our groceries from Bob Graham’s store, even though there were lower prices and a much better selection 25 miles away in either direction. What will you do in a storm, I used to ask my neighbors, if Bob Graham is forced to shut down, and where will you go at the last minute? Does the A & P or Piggly Wiggly give you credit, like Mr. Bob, who only once, when I was four months late, wrote on my monthly bill, “Could you give me a little help on this?”

I have heard all the arguments why WAL-MART is a good neighbor to small towns and how we all come out ahead in a free market with open competition based on price. But I have also seen how these things operate with my own eyes. A mile from my house there is a small shopping center, which used to have both a small, locally owned supermarket and a local pharmacy. When a large national chain decided to open up a super drugstore, it not only took the place of the only supermarket in my neighborhood where I could buy wine, but it also insisted that the shopping center terminate the lease on the old drugstore. To this day, my wife and I try to buy medicine anywhere but from that super drugstore or one of its thousands of sister stores all across the country.

One of the problems with cities like Rockford is not that they are provincial but that they are not provincial enough. The lack of parochial commitments seems to drain community of its life and reduce Main Street America to strip malls and fast-food chains. All good places, whether Paris, France, or Paris, Kentucky, are particular and peculiar, and it does not matter so much whether the local cuisine is crepes or chicken-fried steak, because if it is local, it is bound to be better than any portion-control servings trucked into Chi-Chi’s.

Chesterton and his distributist friends used to tell people to go only to the little shops and to avoid the big stores in downtown London. This policy was due in part to their concern for local community, but it also reflected their conviction that small, specialized shops—greengrocers and butchers and apothecaries—are more human than department stores and supermarkets. In much of Europe, life is still carried out on the human scale, and if we wish to humanize life here in America and make it safe for our faiths, then we must regard every dollar we spend as an investment in our vision of heaven or hell. There is a stupid joke about the man who crossed a parrot with a lion. “What did you get?” asks a stranger. “I don’t know, but when he talks, I listen.” In a commercial society, like Carthage or the United States, money talks, and it talks so loud that it drowns out all the voices of faith and music and love as it parrots endlessly its litany of “the real thing” and “the choice of a new generation.” We must learn to make our money speak our own language. We must learn to make it roar.

Leave a Reply