Facing a recall election, Gov. Gavin Newsom recently announced the state would pay all back rent for qualifying tenants and then, sounding like Jack Bailey in the 1950s TV show Queen for a Day, said, “And that’s not all. The state will also pay all past due water and utility bills!”

“Qualifying” renters include all those who earn less than the median income for their area. Such renters will have their rent paid from March 2020 to October 2021. How many of these people are illegal aliens is anyone’s guess but I suspect it has to be in the tens of thousands.

Gov. Newsom didn’t conclude the giveaway announcement with “Vote for Me,” but who could fail to draw that inference? He also failed to mention that the $5.2 billion allocated for the rent-payment program will come not from the state, but from the federal government. Newsom’s generosity with other people’s money knows no bounds. To be fair, the $2 billion allocated for unpaid water and utility bills is coming from the state. Buying votes is something out of the Third World, but that’s California today.

I suspect most Americans think it was also California yesterday—that the state has always been leftist and whacko. Not so. From the end of World War II and right through the early 1960s a middle-class conservatism developed in California that was not only opposed to the Democratic left but also to the East Coast Republican establishment. I like to remind people that during the era of radical upheaval, protests, and riots in the mid-’60s to early ’70s, California was far more conservative than most states.

It usually shocks people to learn Ronald Reagan was governor in that era, while his equally conservative good buddy George Murphy was one of California’s U.S. Senators. California’s other U.S. Senator was Tom Kuchel, more moderate, but still a Republican. The Superintendent of Public Instruction was Max Rafferty, regularly labeled as far right. Serving in the state senate was a so-called extreme right-winger, John Schmitz, a prominent member of the John Birch Society who would be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1970. Another right-wing representative from California and prominent Bircher was John Rousselot, who served in Congress in the early ’60s and then again all through the ’70s. California sent several other such conservatives to the House during the era.

To a large degree this conservatism was an organic, grassroots phenomenon that had little to do with a conservative intelligentsia and nothing to do with great wealth and power. It was far more a product of the American Dream being realized in California by millions of hardworking, enterprising, freedom-loving, and responsible citizens, many of them veterans of WWII. By the end of the war there were a mere 7 million people (40 million today) in California and land was cheap. California was truly the land of opportunity.

Ronald Reagan was one of these middle-class conservatives. He lived about two miles from me in the small hamlet of Pacific Palisades. I’d occasionally see him around town in the ’50s. At first I knew him only from his movies, which included one of my favorites, Knute Rockne All American (1940), and from hosting the television program General Electric Theater. I thought of him as a big, handsome, and likeable guy—and knew little about his politics. From his years as president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), though, it was clear to adults with a connection to Hollywood that, although Reagan was a Democrat, he was staunchly and outspokenly anti-far left and anti-Communist. Although he voted for Truman in 1948, he voted for Eisenhower in 1952 and in 1956 was active in the Democrats for Eisenhower campaign.

By the late 1950s when I was becoming interested in politics, Reagan’s evolving conservative political views had become well known from his many speeches for General Electric. In the 1960 presidential campaign, Reagan made some 200 speeches for Richard Nixon. Reagan was not a big fan of Nixon but thought the Democrats had drifted too far left no matter whom the party chose as a presidential candidate. Reagan again supported Nixon in 1962 when the former vice president ran for governor of California.

A year later I had my first talk with Reagan. It was at his first ranch bordering Mulholland Highway in Malibu Canyon, not his later one in the hills above Refugio Canyon in Santa Barbara County. A couple of friends and I were riding our motorcycles along Mulholland when I spied Reagan, clad in a plaid shirt, blue jeans, and boots, mending his fence. We motored up to him and were soon discussing the politics of the day, especially the condition of California. We were also soon helping him with the repairs. He seemed genuinely interested in talking with us teenagers, but he may also have been working a little Tom Sawyer on us. Most importantly, though, I found his views resonating with my own, and it would have been obvious to anyone that his genial nature and storytelling ability were made for politics.

A year later Reagan gave what I think was his best speech ever, “A Time for Choosing,” nationally broadcast in October 1964 as part of the campaign for Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. However, the Democrats effectively demonized Goldwater as a far-right extremist who would crush the workingman and get us into a nuclear war with the Soviets. Goldwater lost to Lyndon Johnson in a landslide.

A year after his famous speech Reagan decided to run for California governor and by the spring of 1966 he was on the campaign trail. First, he had to defeat moderate Republican George Christopher in the primary, who had served on the San Francisco County Board of Supervisors and then as mayor of San Francisco from 1956 to 1964. The Democrats thought Reagan, who would be seeking his first public office, easier to defeat and leaked negative information about Christopher to columnist Drew Pearson. That probably had little to do with Reagan’s landslide victory in the Republican primary, but it did cause Christopher to wholeheartedly support Reagan against incumbent governor, Democrat Edmund Brown, in the general election.

Brown and the Democrats then turned their guns on Reagan, hoping to do to him what they had done to Goldwater. They tried their best but Reagan was unflappable and continued to declare he’d “send the welfare bums back to work” and “clean up the mess at Berkeley.” When student protestors waved signs at him that said “Make Love, Not War,” Reagan said the protestors “didn’t look like they could do either.” Brown and the Democrats also attacked Reagan as nothing but an actor and totally unqualified to be governor. When reporters asked Reagan what kind of governor he would be, he’d smile and say, “I don’t know, I’ve never played a governor.”

Reagan won the election in a landslide, 58-42 percent. He won a million more votes than Brown and won 55 of California’s 58 counties. He won an astounding 78 percent of the vote in lightly populated Mono County but also 72 percent of the vote in heavily populated Orange County. He won more than 60 percent of the vote in most of California’s rural counties. Reagan repeated his success, if not his margin of victory, in California’s 1970 gubernatorial election, winning with 53 percent of the vote to Jesse Unruh’s 45 percent.

Reagan was popular partly because of his looks, charm, and humor, but mostly because his conservative policies and attitude resonated with the majority of California voters. Reagan’s success was not an anomaly in the California of that era. The 1964 race for the U.S. Senate pitted Pierre Salinger, President John F. Kennedy’s former press secretary and recently appointed U.S. Senator from California, against actor George Murphy. Like Reagan, Murphy had once been a Democrat but had become a conservative Republican. He was also of Irish descent and a handsome guy blessed with natural charm. He, too, had been a SAG president. In his run for Senate he was attacked as too far right for California and totally unqualified for the Senate. He won with 52 percent of the vote to Salinger’s 48 percent. It was the only Senate seat that changed from Democrat to Republican in the 1964 election.

More surprising than the victories of Reagan and Murphy were those of Max Rafferty. Not particularly handsome or charming and uncompromising in announcing his “far right” views, Rafferty won the election for Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1962 with 54 percent of the vote. Four years later he was reelected with nearly 69 percent of the vote. A brilliant student himself, who had graduated from high school at 16 and from UCLA at 19, Rafferty had a master’s degree and a doctorate and years as a teacher, principal, and school district superintendent by the time he ran for statewide office. He also had two books published describing what leftists were doing to public education, and he would write two more while in office.

Rafferty was pitted against UCLA professor and president of the Los Angeles school board, Ralph Richardson, in the 1962 race. The two agreed to a series of televised debates. My liberal teachers at Palisades High gleefully anticipated a Professor Richardson tour de force against the “right-wing extremist.” They got their tour de force but it was Rafferty’s. Rafferty had almost total recall, could recite facts and figures not only for California schools but for schools nationwide, and could describe in detail the deterioration of schools caused by liberal educators. Moreover, he had concrete plans for fixing things.

As the old joke gripes, “Why is California like a bowl of granola? Because it’s full of fruits, nuts, and flakes.” Maybe so, but I’m old enough to remember when a conservative middle class thrived in California and exercised political muscle.

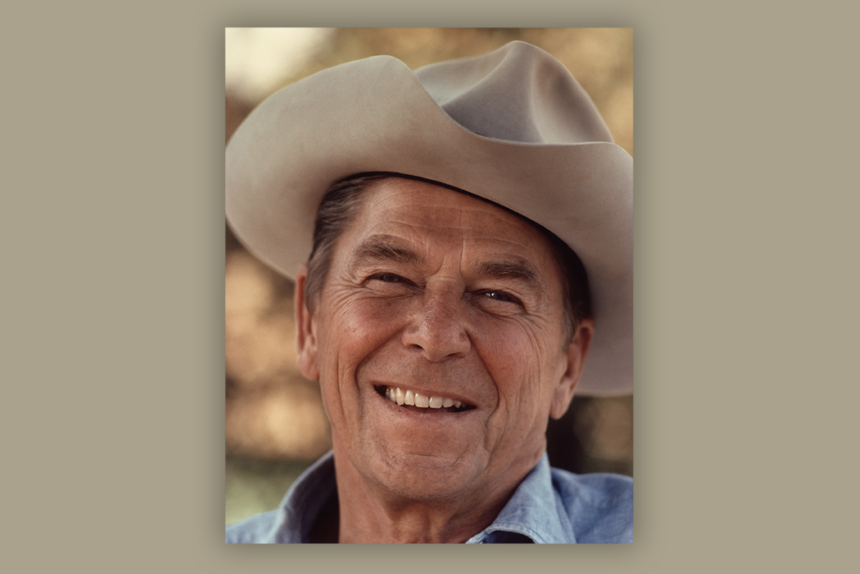

Image Credit:

above: Ronald Reagan on his ranch at Rancho Del Cielo in Santa Barbara, CA in 1976 (National Archives)

Leave a Reply