There are so many difficulties with our National Anthem that it’s hard to keep up with them all. But the explicit question that it asks—whether we see the Stars and Stripes still flying after the twilight’s last gleaming—is actually a pertinent question today, and not only one about the bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814.

So let’s start with some pleasant memories before we get real about the problems. I can remember when I did not know or care that I could not sing the old tune—it’s really a regular hillary just to get through! That’s one big difficulty, and another is that other people couldn’t do it very well either, except perhaps young women from church choirs. But besides the problem of the musical challenge was the obscurity of the words—the verse and even the sin tax—no, I mean syntax. And beyond that was the obscure narrative, based on an incident of bizarre observation—literally from a British warship in the War of 1812. So there is an historical challenge to add to the musical and discursive ones. But somehow I never much worried about those concerns. How could I have worried, when I was preoccupied with giggling about the folkloric revisions voiced by my schoolmates? “Oh say, can you see any redbugs on me? / If you do, pick a few, and you’ll have some on you!”

Alternate last half of second line: “and we’ll make redbug stew!” But the naughtiness of those days was innocent compared with the political steamrolling of today.

Skipping rapidly along, I was never solicited by communists until I went to college. I am not referring to students (such as the two young ladies of my acquaintance who were subsequently jailed for one bombing or another), but to the faculty. The most brilliant lecturer I ever heard was a proponent of the U.S.S.R.—an apologist for a regime remarkable for its illegitimacy. I noted communist appeals as they went by, even in pop hits such as “Imagine.”

But I want to focus on the grand old flag and the National Anthem. My memories of challenged loyalty during the 60’s are quite relevant, for the brazen display of hostility to the only country we constitute was a routine matter in those days, and is so again. The inherent difficulties of “The Star-Spangled Banner” haven’t changed, though new difficulties have been added; but the oblique approaches to the discrediting of the flag and the anthem have changed.

So yes, there are difficulties with the national anthem: It is hard to sing; even a bit challenging to comprehend; and hardly anyone knows the second, third, and fourth stanzas. But today it has become harder to sing than ever before—I know that sounds silly, but it’s true. And the avalanche of political manipulation we have lived through has finally rendered the National Anthem altogether politically incorrect. So let’s get down to cases about the anthem having actually morphed in its challenge to the singer—and to the listener! And then we will address the history of the nation in the new order of being.

In May 1917, John McCormack’s recording of “The Star-Spangled Banner”—including the fourth stanza—was a hit. Decades later, another source of many performances of the anthem was Robert Merrill, a carefully adjusted baritone who served as the chief deliverer of the song for years. And for decades there were all kinds of adequate and even excellent performances across the country, from the sources you would expect. But the correct or traditional performance of the anthem began to devolve into something else when the song was presented as reconceived or decontextualized. This seemed to be so in the televised Super Bowl and has spread from there to such a degree that many people have apparently never heard the song as it was written.

José Feliciano seems to have started the whole thing in 1968 at Game Five of the World Series in Detroit, with a bluesy rendition—an interesting or playful paraphrase, perhaps. A week later, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their clenched fists during a ceremony at the Olympics. Subsequently, Marvin Gaye, Jimi Hendrix, Whitney Houston, and Roseanne Barr have delivered remarkable versions of the anthem, probably most brilliantly by Houston and Hendrix, and most grotesquely by Barr. Most other performances have been embarrassing failures. I suppose that baritones and sopranos who sing at the Metropolitan Opera can cut the mustard, but not vendors of pop music—except Lady Gaga. She can actually sing.

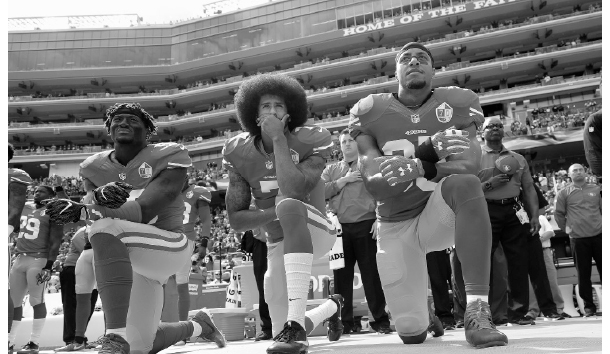

But these latter-day controversial points of style and performance, though both interesting and destructive of the anthem’s claim to its exalted position—a position that is of questionable dignity as connected to television and sports—are also related to other matters that have been brought to our attention. Colin Kaepernick, the rich and challenged backup quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers, has initiated a protest by refusing to stand for the performance of the National Anthem because of the oppression of black people in America, past and present. He has received much attention for this position, including the support of the President of the United States for his right to protest.

But there has been an angle of attack on the anthem itself, and the author of its lyrics. Francis Scott Key has recently come to belated national attention for his historical derelictions, such as owning slaves, and other questionable episodes in his life as a lawyer in the District of Columbia. But the most telling discredit to the author and the anthem is from the third verse, which includes the passage “No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.” The hireling would be the Hessian mercenary, and the slave would be perhaps impressed sailors or, more likely, the Colonial Marines, as the British called the slaves who would be rewarded with freedom for fighting against their rebellious masters or owners.

But the language about the hireling and slave is even more striking than the revisionists have claimed, for the same idea was also mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, and for the same reason. In the Declaration, the British sought to turn the slaves against their masters by offering them their freedom as a reward for supporting the British side in the American War of Independence. They obviously did this again in the War of 1812, but during the Civil War or the War Between the States, it was the United States which played that card, which does put the story in a new light, though not the one that Colin Kaepernick and others have in mind. When it was too late, by the way, the Confederates considered that card as well, and even made a beginning on instituting it. Independence trumped slavery, in that calculus.

In the Declaration, the King “has incited domestic insurrections among us”—from Indians, for one example, and from slaves as well, as proposed by Lord Duns more in Virginia, in November 1775. The British had a more humane policy about the Indians as well as about black slaves, and not only that. They also had an anthem with a tune that was more singable, without the octave and a fifth range of our own Star-Bungled Bummer. They called it “God Save the King” (or Queen), and we call it “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” In our version of that song, as we all know, we get to sing about “the Pilgrims’ pride,” which confirms a distortion we somehow still find necessary.

The Civil War proved that the American War of Independence was a mistake, in several senses. But what proves that we need the Stars and Stripes, or the song about it either? Why is patriotic piety addressed at a televised professional football game, or at any other such game? I don’t see much of value in the game of football now, though I did years ago, when amid the clumsy violence, Lynn Swann flew like a bird. What I see now is a rough struggle of little interest. Any imposed connection to national pride is absurd. Even so, the fans who paid high prices to get into the multimillion-dollar stadiums constructed from corrupt tax dollars didn’t contract for political theater. They already had enough of that, from the “game” or bloated business itself.

We don’t need professional football, any more than we need “The Star-Spangled Banner,” which was never the national anthem until 1931. The revealingly blasphemous “Battle Hymn of the Republic” would serve, or “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” or whatever. Neither do we need the Stars and Stripes, for so many years the flag of a slaveholding nation. Since both the flag and the song about it have been discredited, we should look at revamped iconographies and other colors for the flag and begin anew in a reformulated nation. We can thus avoid not only steroid-boosted football games, but any further crises of individual and mystic impositions of anachronistic and imaginary justice.

A more singable anthem would be less provocative of abuse as well as more familiar, appropriate, and appealing. John Lennon’s (or Lenin’s) musically and ideologically banal song “Imagine” would be right for our historical moment. It doesn’t have to be dumbed down. It doesn’t have to be supercharged with a beat instead of rhythm, melisma instead of substance, or blaring missed notes that are disfigured with tonal collapse, as the Star-Bungled Bummer routinely is.

Let’s face it: When something organic has died, it deserves a proper burial or, if not that, at least some process of removing the remains from the side of the road. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony survived being treated as disco music, but that was done only once, though played often. Our anthem—our racist anthem—has been trashed often; that is how it is known. The time to dispose of the road kill has long since arrived.

A new nation redeemed by supervised social justice, unfettered by grumpy constitutional obstructions or clingy religion, bound by the musical vision of Lenin, and inspired by drugs would be in step with the Zeitgeist, as we hasten to grasp the right side of history. “Imagine there’s no heaven / It’s easy if you try . . . ”

Leave a Reply