It is a strange experience, after an absence of 25 years, to revisit a city with which one was once linked by ties of solidarity. Stranger still was it to discover that Berlin, while it has been extraordinarily transformed in many respects, has remained extraordinarily unchanged in others.

Probably in no other European capital today is this contrast between a recent, crippling, hemiplegic past and a relatively healthy, unfettered present more pronounced than in this still war-scarred city—as though its present, hesitant predicament (What kind of city should it strive to become?) had been foreseen by Goethe in Faust’s troubled confession to Mephistopheles: “Zwei Seelen kämpfen, ach, in meiner Brust.” (“Two souls, alas, battle in my breast.”)

But first, a few words of explanation. On August 13, 1961—not for nothing was it a deliberately chosen Sunday in the middle of Europe’s somnolent holiday season—I was aroused from my torpor on France’s Côte d’Azur by the dramatic news that the East Germans of the so-called German Democratic Republic (GDR) were now doing what had long been thought impossible, by cutting the city of Berlin in two. A few weeks before, Walter Ulbricht, the GDR’s communist boss, had blandly declared, “Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten.” (“No one has the intention of building a wall.”) Yet, here were his armed Volks-polizei doing just that, by rolling out coils of barbed wire—it was weeks before anything resembling a wall began to appear—across scores of pedestrian crossing points between the Soviet-controlled East sector and the three Western sectors of Berlin. Even more effectively, the East Germans were interrupting all further inter-sector traffic on the underground U-Bahn subway and the overhead S-Bahn railway system, which, up till then, had enabled the partitioned city to maintain a minimum of metropolitan cohesion.

There was, however, no sign on the spot of any energetic response from the American, British, or French occupying forces to this flagrant breach of the four-power statutes governing the city, statutes which had been solemnly endorsed at the Potsdam Conference of 1945.

The moment I returned to Paris, I began bombarding Edward Weeks, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, for which I was then working, with letters insisting that what had happened was more than a mere “incident” and that we should do something to manifest our support for the understandably nervous West Berliners. I flew to Berlin, where I was received by Gen. Lucius Clay, President John F. Kennedy’s personal envoy, who welcomed my suggestion that the Atlantic devote a special issue to Berlin.

With the help of his press secretary, Jim O’Donnell—a German-speaking Kalter Krieger (Cold Warrior) who had been the first American journalist to penetrate Adolf Hitler’s Führerbunker (before it was blown up by the Soviet occupying authorities)—and of my old translator friend, Walter Hasenclever, we put together a special issue, which the Atlantic finally published under the title “Berlin: The Broken City.”

The first thing that struck me when I returned there last January was the feeling of space that this vast city conveys—a result, partly, of the fact that, with a population of 3.4 million who inhabit an area of 344 square miles, Berlin has a population density 20-percent lower than that of Greater London (9,884 inhabitants per square mile, compared with 11,987). Its two punctual metropolitan railway systems also help to explain the absence of urban congestion, exasperatingly evident today in so many other German cities, as in the Greater Paris area of the Ile de France, with its 10.5 million inhabitants.

Whereas London, like Paris, boasts only one major river, Berlin has two, the Spree and the Havel, in addition to a number of connecting canals, which are crossed by close to 2,000 bridges—four times the number in Venice. It also includes more than a dozen lakes, as well as the huge, aptly named Grunewald—the “Green Forest,” which is four times the size of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris and inhabited, it has been estimated, by more than 6,000 wild boars!

These geographic details help to explain the West Berliners’ ability to survive the claustrophobic ordeals of an 11-month blockade (1948-49), when everything, including coal, had to be flown in to West Berlin’s two airports at Tempelhof and Tegel in twin-prop Douglas DC-3s. Less well known are the numerous garden plots that their rustic ancestors had thoughtfully preserved against predatory “builders,” which greatly helped the beleaguered West Berliners to survive their grim encirclement.

The abundance of rivers, canals, and lakes offers Berliners sporting attractions—swimming, row boating, yachting—unmatched by any other European capital, with the possible exception of Stockholm. Thanks, too, to the extensive greenery—Berlin has nine times as many trees as Paris—the city is blessed with something the damp, often fog-bound makeshift capital of Bonn never had: bracing air, air of such invigorating purity that it long ago inspired a local (for its inhabitants, a truly “national”) anthem, “Die Berliner Luft,” ceremonially used on “great occasions” to greet such prominent visitors as Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Jack Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan.

“Berlin,” a recently retired German diplomat explained to me whimsically, “has had to endure three successive destructions. The first was the destruction caused by the wartime bombings of the Second World War. The second was the shoddy rebuilding effort launched in the immediate postwar years. The third, begun in the 1960’s in the West, was a program of destruction aimed at removing the makeshift buildings of the immediate postwar years in order to replace them by more ‘modern’ structures. Berlin has thus lived in an unsettling state of permanent architectural revolution that has continued to this day.”

Regardless of what one may think of some of the architectural results, it is difficult not to be impressed by the scale of Berlin’s reconstruction, even though no fewer than seven huge heaps of still-unremoved Teufelstrümmer (“devil’s heaps” of rubble) remain visible in various parts of the once-battered city. No one traveling on the S-Bahn between Bülowstrasse, at the northeastern end of the Kurfürstendamm, and the Potsdamer-Platz can fail to notice the dismal state of the bombed-out no man’s land that once separated the eastern and the western sectors of Berlin.

That said, the Kurfürstendamm is once again the fashionable artery it was in the pre-war years. But it has been kaleidoscopically “modernized” by the architectural intrusion, among the remnants of pompous Wilhelm II and art-deco edifices, of rotund and triangular, as well as square-paned steel-and-glass, monoliths, which glitter spectacularly at night. One of them is the huge, seven-story KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens) department store, reputed by certain guidebooks to be the largest in Europe.

Politically as well as culturally, however, the center of gravity has been moving inexorably eastward to the central Mitte district of Berlin, once the administrative center of Hitler’s Third Reich, and of its longer-lived Soviet successor. The obstructions that used to block more than 60 transit points between East and West Berlin have all disappeared, and anyone who wants to can now drive in an almost straight line from the vicinity of the Charlottenburg Castle in the West through the wooded Tiergarten on Europe’s longest and broadest urban thoroughfare—the so-called Strasse des 17 Juni, which commemorates a brutally crushed revolt of East German workers in 1955—past the Brandenburg Gate and eastward along the once-elegant and now more prosaically rebuilt Unter den Linden artery all the way to the river-and-canal-surrounded “Island of Museums,” which includes the famous Pergamon as well as the completely restored cathedral, with its crypt containing the remains of 95 Hohenzollern rulers.

No attempt has been made to restore the pre-war pomp of the prestigious Wilhelmstrasse, where once were located the Führer’s Reich-Chancellery and Ribbentrop’s Foreign Ministry. The appropriately renamed Bundeskanzleramt, or Federal Chancellery, where Angela Merkel now has her offices, is housed some distance to the north in a huge, nine-story complex of buildings located at the northeastern end of the Tiergarten, next to the Spree.

From there, it is an easy walk to the once totally gutted and now completely rebuilt Reichstag, where the 614 deputies of the Bundestag can argue and debate in an amphitheater wondrously lit from above by a transparent dome ingeniously designed by British architect Sir Norman Foster to provide a maximum of natural daylight with an inbuilt circumference of 360 mirrors.

Adjacent to the Wilhelmstrasse is a shrub-and-thistle-infested plot of vacant land that is still waiting to be rebuilt. It was here, on the notorious Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse, that Heinrich Himmler and his deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, developed and expanded the headquarters of the dread Gestapo. After years of anguished debates, it was recently decided that this accursed site should house a museum exposing the horrors of the Nazi past—one of a dozen museums that have so far been opened to brand the villains or to honor their victims and those who, like Count Claus von Stauffenberg and other members of the July 20, 1944, plot, strove to resist Hitler.

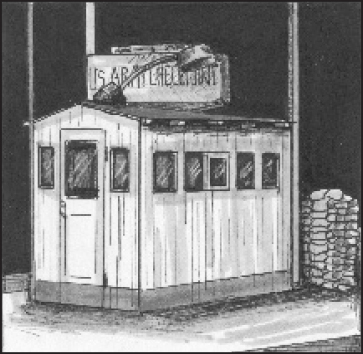

For a Cold Warrior such as myself, it was particularly gratifying to discover that at least one Berlin landmark has been preserved as a memento. This is the control booth on the Friedrichstrasse, dubbed “Check-Point Charlie” by our GIs, which, from the moment the Wall began to rise in August 1961, became the only passageway for vehicles between the Russian and Allied sectors. The Russian control booth, with its maze of zigzagging concrete blocks, has disappeared, but two huge photographs of a bemedaled GI, mounted on a central pillar along with the warning sign, “YOU ARE LEAVING THE AMERICAN SECTOR,” still adorn this once-famous crossing point on a major north-south artery where cars and buses now travel freely.

Nearby is a souvenir shop, advertising itself as the “Haus am Checkpoint Charlie,” where everything from postcards, magazines, and books to the pram that was once used by an East Berlin mother to stage a daring escape from East to West keep alive the 28-year-long history of the infamous Wall. Initially, it was a kind of log cabin erected by an already white-haired Original (i.e., a crank) named Rainer Hildebrandt. The son of a Stuttgart painter and a Jewish mother, Hilde-brandt, whom I befriended while doing research for a book on the Berlin Wall crisis of 1961, was then regarded by many Berliners as a crackpot. Though generally no lover of souvenir shops, I was pleased to see that a younger generation of Berliners had decided to maintain his “house” after his death two years ago. For what he epitomized in his naive determination was the spirit of resistance and feeling of gratitude to America which, on a higher level, the rock-ribbed Ernst Reu-ter, West Berlin’s first mayor (1947-53) and the founder of its Free University had so indomitably displayed during the first postwar years.

A spirit which, corrupted by party politics and the wild euphoria of the post-Wall 1990’s, when everything suddenly seemed possible, is no longer visible in a now almost bankrupt city.

Leave a Reply