When he was little, Rick Curry was the first of his friends to tie his own laces. That may not seem like such a big deal unless you know that he was born without a right forearm. He was brought up to believe he was completely normal.

At six, Rick’s father sent him to an acting class to give him self-confidence, in the hope that Rick might become a lawyer. Instead, he fell in love with the theater. But it was at his Jesuit high school that Curry found his true calling. The Jesuits really appreciated the intellect, he said. “They taught you how to think. That was something I didn’t have any barriers to.”

A Jesuit priest, Father Curry died in 2015, at the age of 72. He dedicated himself to teaching people with disabilities how to succeed—first in the difficult world of theater, then with wounded veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan, helping them deal with post-traumatic stress by writing of their experiences. His tools were stagecraft and storytelling.

His life was celebrated in October 2016 with a memorial service at the Sheen Center in New York, not far from the theater program he founded in lower Manhattan. Most memorably, the service showcased the cabaret choir of his National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped—some crippled, some stunted, one blind and led on stage, one in a wheelchair—joyously singing, “Because I knew you, I have been changed for good” and “You fill my cup with happiness.”

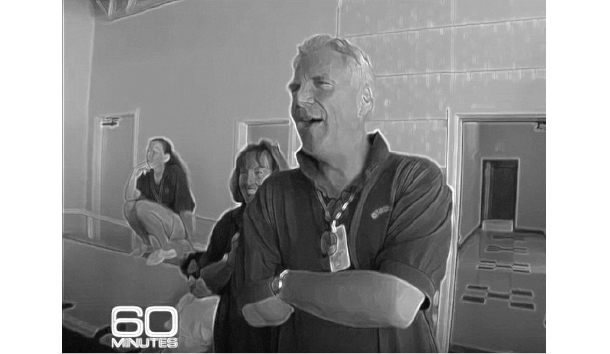

Other than missing one arm, Curry was a presence with rugged good looks and an athletic build from swimming, ice skating, and skiing. Always in motion, often in Bermuda shorts (and short-sleeved shirts), he would bound around on stage directing students. His blue eyes twinkled, and his cheeks dimpled when he smiled, which was often.

Father Curry spent most of his ecclesiastical career as a Jesuit brother, a humble vocation he happily embraced for its commitment to service and its closeness to parishioners in the pews. He was proud of being a brother, the backbone of the Jesuits. “Not one of those cushy priests,” as he put it.

That changed after 45 years, when he was asked to counsel a wounded Marine veteran, an amputee back from overseas service who had also lost his wife. The vet came in fired up and angry, soaking from the rain, clearly unhappy about being there. Curry spent hours with him and finally calmed him down. The vet then said that he thought he was ready for absolution.

“I can’t absolve you from your sins,” said Curry. “I’m just a brother. Not a priest.”

“You tricked me,” the vet snapped, upset after investing hours of emotional energy. “You’re a Jesuit, aren’t you?”

“Yes, but I can’t offer sacraments or absolution.”

When the vet asked him why he wasn’t a priest, Curry explained that one has to be called.

“Who calls you?”

“God . . . or the people.”

“Well, I’m effing calling you. I want you to be a priest.”

This kind of thing happened often enough that Curry went to his spiritual advisor, telling him that he wanted to heal souls as well as work with the disabled, and that he wanted to study for the priesthood. It wouldn’t be easy. Even though he was bright, and already had a Ph.D., he would be a nontraditional student, starting a rigorous course of study—at 60.

Granted permission to study at the Catholic University of America, he ultimately gained special permission from Rome to be ordained, after dealing with reservations along the way. Because canon law requires two hands to celebrate Mass, one priest questioned his ability to offer the sacraments: “You know, you only have one arm.”

Curry pretended to be surprised at this revelation. “Really? I hadn’t noticed that.”

An irreverent sense of humor combined with deep faith was the mark of the man. He referred to his disability as a blessing: “The greatest gift I’ve ever been given is to have been born with one arm.” Then: “I’d rather have one arm than be bald.”

He often related his experience as a theater intern when, facing raw prejudice for the first time, he was turned down for a mouthwash commercial. The receptionist thought that he was sent as a practical joke, burst out laughing, and refused to send him inside. “I was stunned, I was hurt,” he reacted. “There was no way I could convince her that having one arm wouldn’t stop me from gargling nationally.”

That experience led to him launching the National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped, to train men and women with physical disabilities to be actors, singers, even dancers, and to help them get jobs in movies, shows, and commercials. He acknowledged that most would fail, but pointed out that so do most actors who are not disabled. Yet acting skills are transferable, making people better communicators, more articulate, and more successful in business.

Over the years, Curry directed 150 shows and trained 9,000 disabled performers, telling audiences, who had been trained not to stare at disabilities, to stare at the actors. “If you like what you see, applaud. We don’t want you to applaud the disability. We want you to applaud the achievement.”

Curry believed that the transformational power of the arts was bigger than any physical limitation, having seen the power of black theater, women’s theater, and gay theater. He was convinced that the disabled were a group waiting to happen.

In his classes, he talked about theater, not disability. “Spencer Tracy said to be a great actor, you come on time, you memorize your lines, and you don’t bump into the furniture. I say, you will memorize your lines, you will come on time, and my staff will see that you don’t bump into the furniture.”

His theater workshop operated in a 50-seat theater in lower Manhattan, later adding a residential workshop in Belfast, Maine. To support this enterprise, Curry was inventive in raising money. In addition to making private donations and giving benefit performances, he wrote two successful cookbooks (Secrets of Jesuit Soup Making and Secrets of Jesuit Bread Baking), trained students to bake (giving them a trade), and sold specialty breads by mail. Concluding that he needed a product with better shelf life than bread, he added dog biscuits—“Brother Curry’s Miraculous Dog Biscuits.” Miraculous because of the cause they helped support.

Fundraising, always difficult, became unsustainable when he moved to Washington to continue his priesthood studies, so the theater and bakery had to be closed. But Curry continued to work in disabilities in D.C., founding Dog Tag, Inc. to help wounded veterans transition to civilian life with an education at Georgetown University, and hands-on small business experience in a bakery.

“I didn’t go to a one-handed school that taught me to live in a two-fisted world,” he told one interviewer. “I had to adapt. It wasn’t always easy, but if that is the gift that God had given us, I say let’s celebrate it. Embrace all your limitations—they too are gifts. And accept other people’s limitations. Never forget that He who gave you these gifts, He makes no trash.”

Asked on 60 Minutes about the assumption that it’s better to be able-bodied than to be disabled, Curry argued: “I think it’s indifferent. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, would say, ‘That’s indifferent. It depends on how you use it.’”

Leave a Reply