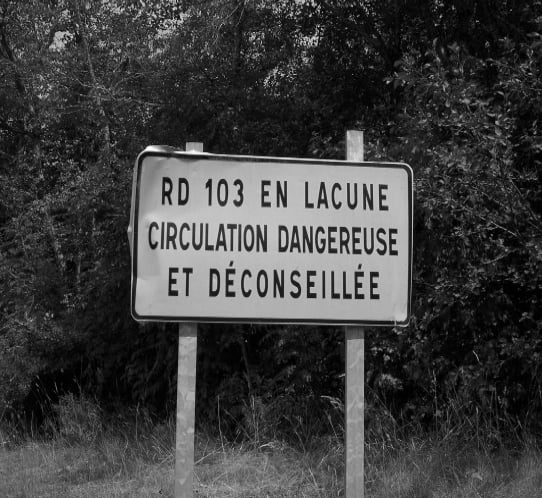

We had known it was a “white road” when we had found it on the map, but when my wife and I got to the start of it, we hesitated. There was a sign at the junction, and it made us stop and think: RD 103 EN LACUNE CIRCULATION DANGEREUSE ET DÉCONSEILLÉE.

En lacune wasn’t a phrase either of us had come across, and we had left our French-English dictionary back in England. I did, however, have a Latin-English one back in the tent. It wasn’t there because I had expected to meet ancient Romans—though a couple of thousand years ago, we might well have come across a few in the Alpes de Haute-Provence. The book was a stowaway; it had found its way into one of my hastily packed bags. When I looked up lacuna later, I found that the reason that we use it to describe a place where something is missing in a manuscript is that the word’s primary meaning is “a hole.” By then, though, we had worked this out for ourselves, for the RD 103 has more holes than surface, and what surface it has is covered with stones, rocks, bigger stones, bigger rocks, and—at the point at which we decided our car wouldn’t take any more—boulders. Driving up that road had indeed been “dangerous,” and we could see why the sign advised against it.

The drive had, however, been spectacular. The RD 103 followed the river, the river followed a gorge, and the gorge narrowed to a clue, a cleft between two tall cliffs. Beyond it, the valley opened out, and the road rose steeply, crossed by runnels made by spring water falling from the mountainsides above. On foot now, we unfolded the local map. We were amused to notice that one of the springs had a name: Source de Pisse Vache. We didn’t need a dictionary to work that out. Another detail we had missed when we planned our expedition was that the place names ahead were all followed by the word Ruines. The valley we were exploring had been abandoned. We were in the definitive back of beyond.

Which is why, when we looked up after drinking at a spring, we were surprised to find ourselves facing a man, and shocked when we saw that he was carrying a four-inch, open-bladed Opinel pen knife—though our alarm did subside a little when we saw that, in his other hand, he was holding a lettuce. He must have come to the spring in order to wash it. But what on earth was he doing all the way up here? He stood in silence, waiting for us to speak. He was tanned, unshaven, and wearing a ragged polo shirt, shorts, and flip-flops that were at least two sizes too big for his feet. “Bonjour!” I said.

He returned the greeting, and resumed his silence. For want of something to say, I asked him how to find the path to the top. “Suivez moi!” he replied, and disappeared behind a pile of stones that had once been a wall.

We followed, and found ourselves standing in front of an old caravan. If caravans were marked on maps, I thought, the name of this one would surely be followed by the word Ruines. It sagged on its chassis, and its door hung open, revealing a jumble of clothes, boots, tools, and packets and tins of food within. Heaven only knows how he’d got it there. Outside it was a rickety wooden table, on which there were a stack of disposable plastic beakers that had clearly been reused (but not rewashed) many times, two tired-looking carrots, and a tin plate. He put the lettuce on the plate, and a swarm of flies settled on it.

“Vous etes de quelle pays?” he asked.

“England,” I replied.

“Ah,” he said. “What ees mouches in Eenglish?”

“It’s ‘flies,’” I replied, and more appeared, as if the word had summoned them. My wife caught my eye and raised hers to a branch in the tree that shaded the caravan. There was a flypaper hanging from it, but it had only caught two, and, from the look of them, quite some time ago.

He reached through the door of the caravan and pulled out a bottle of Pastis. “Un aperitif?” he asked. I looked at my watch. It was only 11 o’clock, but it seemed rude to refuse. He took the top three beakers from the stack and inspected them by holding them up to the sun. They did not sparkle. He set one aside, then picked it up again when he found the next even dirtier. He poured a good slug into each and topped them up with spring water. As we stood there, nursing our drinks, I asked him whether he was on holiday. It would have been rude to ask if he had fled the cruel world after a crisis, which is what I was thinking.

“Non,” he replied, and made another stab at English. “I am berger,” he said. “What is berger?”

“Ah,” I replied. “A ‘shepherd’!”

He pointed to the opposite hillside. “These—are—my—sheep. I—have—nine-hundred!”

I began to think of him in a different light.

“I live here three months each year,” he continued, more confidently. We followed his eyes as they turned to the caravan. “Three months is a long time,” he said. The words cabin fever began to form in my mind.

We raised our glasses, toasted each other, and it was time to go. He led us just up the hill to the track. Parked beside it was an ancient Citroen, looking every bit as out of place as the caravan—more so, indeed, for across its bonnet was a message stenciled in huge white letters: “Lisez L’Evangile!”—“Read the Gospel!”

“I see you are a Christian,” I said.

“Bien sur!” he replied. “Et vous?”

“Yes, indeed.”

Then, breaking into a smile that set his eyes sparkling, he said: “The Lord is my shepp-ed; I shall not want. Psaume twenty-three! God—bless—you!”

“I was a stranger, and you welcomed me,” I replied. “Matthew, twenty-five. God bless you!”

Leave a Reply