Last week, we received word that Marion Montgomery was dying. He had been diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of cancer only days earlier and had already fallen into the deep sleep that so often precedes death. By the weekend he was gone.

The funeral was held on Saturday in an Anglican Catholic Church in Athens, Georgia. The pews were jammed with kinfolk, parishioners, academics, former students, and a lot of faces you didn’t expect to see—country people: a long-bearded man in overalls, women in full-skirted cotton dresses, perhaps a little uncomfortable in a church where people genuflected and made the Sign of the Cross.

Few of these had ever read a word Marion had written, but they knew him as a friend and neighbor working on some secret project in a small, second-story office in the tiny town of Crawford. When they asked him what he was doing up there, he would say, “I’m building an airplane.”

Actually, he was writing poetry, fiction, and commentary; hundreds of poems, some of them collected in three volumes; numerous short stories, three substantial novels and a novella; and 17 books of literary and cultural criticism. He wrote most of these on an upright Underwood typewriter that dated back to the 1930’s. After he finished the first draft of a manuscript, he would turn it over to a typist; and when it was returned to him, he would revise it and give it to the typist a second time. One day, when he was visiting me, I took him up to my office and showed him a computer.

“If you compose on this, you won’t need the typist.”

“You don’t understand,” he said. “I like to move paragraphs around. Even pages. And eliminate whole segments.”

Quickly, I showed him how easy it was to move passages, delete them, then print the final product. He smiled and thanked me for the demonstration. I believed I’d made a genuine contribution to his literary career. Several years later, when I asked one of his daughters if he’d switched to the computer, she said that all the keys had fallen off the old Underwood, but he was now using an upright Remington. Mel Bradford once said you could tell a true conservative not by how he felt about the automobile, but by how he felt about the wheel.

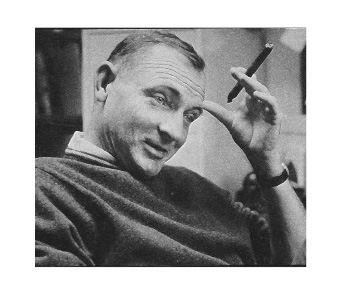

Marion’s attachment to the Underwood was not an affectation. There was less of that in him than in any academic I’ve ever known. If you’d sat down next to him on a park bench and struck up a conversation, you’d have thought he was someone who did something pragmatic, like a plumber or truck farmer or undertaker. You’d never guess he was a college professor, a man who had read thousands of books, introduced them to young people, and taught an enlightened discipline of mind and soul. He had a country face and accent that didn’t seem to belong in the classroom, but in some more honest place.

While still intellectually active and inexhaustibly talented, he gave up poetry and fiction to write in a genre of his own invention, one difficult to describe. Some of the titles hint at its nature and magnitude: Hillbilly Thomist: Flannery O’Connor, St. Thomas and the Limits of Art (2 vols.); The Prophetic Poet and the Spirit of the Age; T.S. Eliot: An Essay on the American Magus. In these and other volumes he used contemporary literature as a key to unlock a secret door to the modern world. The writers he chose were mostly believers in the great tradition of Western Christianity, who—in a variety of ways—challenged the spirit of their own times through irony, allusion, the grotesque. In these books he was a literary critic who analyzed form and style to show the impact of the modern mind on 20th-century poetry and fiction. On the other hand, he explored contemporary literary technique as a cultural phenomenon and in so doing cast light on philosophers from Aquinas to Locke to Teilhard de Chardin.

In these books he spoke both to literary critics and to philosophers—but not to the typical undergraduate or even to the average Ph.D. candidate. These studies are far more demanding than most volumes on the reserve shelf of a major research library, in part because he asked his reader to be almost as well read as he was, in part because the structure of his argument always followed the shape of his infinitely subtle mind, never a straight line from Point A to Point B, but meandering, reversing, crossing back over itself to make certain that every nuance was touched and expanded. I believe these volumes—little understood today—will one day be regarded as among the handful of true documents that tell our descendants why Christendom fell to pieces in the United States of America.

Too often obituaries speak of the valiant fight the great man put up to stave off death. That could be another way of saying he was scared to die. Such was not the case with Marion, as his wife of 60 years, five children, and 21 grandchildren all testified. They found in his almost joyous farewell to life and loved ones the embodiment of the vanishing world he had defended so magnanimously for the better part of 87 years—an old warrior happy in defeat and cheerfully unafraid.

Leave a Reply