Every April since 1981 the American Society of journalists and Authors sponsors an “I Read Banned Books” campaign. They routinely trot out copies of children’s books like Alice in Wonderland or Mary Poppins and modern classics like Ulysses—all of which have been censored by somebody somewhere. One of them inevitably quotes Jefferson on tolerating “error of opinion,” and some professional librarian is sure to warn us that if the prudes have their way, they will soon be removing copies of Shakespeare and the Bible from the library shelves. This year the New York City Library has chimed in by commemorating 1984 with an exhibition, Censorship:500 Years of Conflict. The exhibition catalogue is a volume of essays celebrating absolute freedom of expression. In his preface, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. discovers only two reasons for censorship: fanaticism and fear. Most of this righteous indignation is directed at right-wing groups like Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum or the Moral Majority. Once in a while they make a token reference to the far more effective campaign being waged by civil rights activists who are bowdlerizing Huckleberry Finn or the radical feminists who want to make pornography a violation of women’s rights. In one of the strangest mésalliances of recent years, fundamentalist preachers and journalists are working in tandem with the feminist (often lesbian) activists in the crusade against dirty movies. On the other side, more libertarian conservatives are resisting any government encroachments on the right to read smut. Politics, as they say, makes strange bedfellows, and the new censorship coalitions are beginning to resemble a weekend at Fire Island.

Discussions of pornography and censorship usually turn on the question of rights. Pornographers argue that we all have a legal and a natural right to read, write, and publish anything we like. Neither the interest of society nor simple prudence can compel anyone to surrender one inch of these inalienable rights. Besides, as they are fond of saying, you can’t legislate morality. Feminists also take their stand on rights. Equal rights for women—as defined by all the legislation that is supposed to make ERA unnecessary—means that women are not to be used or exploited as mere things or instruments of a man’s pleasure. Since pornography can be shown to incite rape and—still worse—inculcate generally sexist attitudes, women should have the right to sue their exploiters. Fundamentalists make a similar case. Not only is pornography an abomination in the eyes of the faithful, it is a violation of their right to privacy and their right to rear their children in a wholesome environment. Smut is a moral pollution which should be controlled as much as SO2 in the air or dioxins in the water supply. This healthy environment argument is very similar to the proponents of sex education. The Sex Information and Education Council of the United States declares that “free access to full and accurate information on all aspects of sexuality is a basic right…for children as well as adults. “Most fundamentalists would find it difficult to tell the difference between plain old pornography and the kind of “full and accurate information” sometimes provided by SIECUS and Planned Parenthood. The arguments are similar but the premises—and therefore the conclusions—are opposite.

The major trouble with the language of civil rights is that it is very difficult for anyone to arbitrate between competing claims to determine which set of rights and values should prevail. It used to be possible to escape from abstract rights into the more secure ground of the U.S. Constitution. Once upon a time, the Constitution was fairly clear. It forbade Congress to make any laws restricting freedom of speech or freedom of the press. That duty, according to the Tenth Amendment, was left up to the states. It goes without saying that the framers did not intend to protect smut peddlers or child molesters. (In simpler times there were more informal ways of dealing with sociopaths.) The First Amendment does not actually say anything about filthy pictures or blue movies or even dirty novels. In the 18th century freedom of the press meant only that the government would allow newspapers and journals of different parties to express their opinions. But the clarity of the Constitution became utterly fouled up when the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal rights got affixed to the Bill of Rights. The Congress and Supreme Court are now free either to defend or invade the liberties of states, communities, and individuals—so long as it is in the name of equal rights. What they do depends only on the opinions of whoever is in power.

Rather than all this talk of rights, it would be refreshing to hear the censorship question expressed in the language of social obligation. The plain fact is that humankind is not a solitary species like the orangutans, who seem to meet only to mate or quarrel. Men everywhere live in families and communities. They have always exercised some sort of social authority to keep down the excesses of individualism: theft, murder, and rape; worshiping false gods or spitting on the sidewalk.There has never been any question (exceptamong libertarians who don’t regard themselves as social animals) about a society’s obligation to protect itself or about the duty of citizens to bear the burden of expectation imposed by “the authorities.” In different places and times, people may play by different rules, but there is no game without rules. The old proverb,”when in Rome…” is not just a comment on human diversity. It is much more a recognition of the social facts of life. Dressing up like a priest may get you a few laughs on Saturday Night Live, but when Father Guido Sarducci tried it in the Vatican,he was arrested for impersonating a cleric.

No society has ever failed to censor morals and manners.There is said to be honor among thieves, and even convicts doing hard time apparently cannot abide a child molester. They have a sufficient sense of justice to turn the state’s term of imprisonment into a sentence of death. Some societies are as rigid as the Massachusetts Puritans or as tolerant as London in the 1890’s. None, however, has repudiated its right—its obligation—to suppress public deviance, whether it is manifested in the form of behavior, the arts, or even conversation. This obligation cannot be expressed as a question of individual rights. It is a collective responsibility for thecommon good. In this respect, the feminists are as wrong as the pornographers. This is one area where we cannot allow government to divest itself of its responsibilities.

The censor is always with us. In small, uniform communities—a hamlet in the Ozarks—most people know what is expected of them, and there is little enough occasion for either the sheriff or the censor to intrude. The informal system of gossip and shivaree used to be enough. Most of us today, however, live in more complex, pluralistic communities, composed of people from many different backgrounds. A uniform code of morals and manners is as impossible in Chicago as it would be for the whole U.S. Opponents of censorship seize upon this notion of democratic pluralism and conclude that it is impossible either to legislate morality or to impose the ethical perceptions of one group upon another. Still, the mayors and police chiefs of Chicago do not throw up their hands in despair. Because a significant minority of citizens make their living by burglary and mugging or prefer rape to racquetball, this does not prevent the city from legislating on questions of right and wrong or enforcing the moral opinions of the majority.

The question of censorship is difficult but not impossible. Once we quit ducking down the blind alleys of civil rights, First Amendment freedoms, and moral relativism, we can confront the facts of life head-on. Mankind has always and will always “legislate morality.” Even the advocates of pornography want their activities protected by law. It is a question of a power struggle between opposing moral visions. The Moral Majority wants to defend purity, while the pornographers would agree with D.H. Lawrence (Pornography and Obscenity) that the main thing is to “kill the purity—lie.” All societies not only have the-right to exercise control over words as well as deeds, they all do it. The only question is how far are we willing to go and on what basis. Some varieties of indecency, for example, are tolerated nearly everywhere. It may even have an important social function. In any case, it is usually restricted to certain places and occasions. The Athenians of Pericles’ time were not a licentious people. They were notable for their religiosity in an age of skepticism and for the careful watch they kept upon the virtue of their wives and daughters. Nonetheless, once or twice a year at the festivals of Dionysus, the men of Athens were entertained by comedies which travestied their gods and which used a sort of graphic language which still can bring a blush. Everyone knows of the gentlemen’s clubs which flourished in Victorian London, to say nothing of the English toleration for the “love that dares not speak its name.” Oscar Wilde had to make his vices public before he would be prosecuted. In the United States there used to be places one could go and publications one could order in plain brown wrappers. In fact, most American communities did not attempt to do away absolutely with strip shows or dirty French novels: they only wanted to keep them in their place.

Up until recently, Americans relied on the well-worn distinction between public and private. Private vices, like a taste for exotic art or a collection of designer dresses in a businessman’s closet, were conveniently ignored so long as they did not become so public as to create a scandal. At that point, it was felt, connivance became official toleration and toleration turned into encouragement. This doctrine of privacy between consenting adults is still a wholesome one—up to a point. The hard-core pornography of the 1980’s is a far cry from Fanny Hill: rape, torture, and murder have become commonplace, to say nothing of the ever-expanding market for what is cutely called kiddie porn. Even D. H. Lawrence wanted to censor real pornography “as the attempt to insult sex.” It is just possible that our rising rates of sexual violence and child molesting are not entirely unrelated to the injection of violent pornography into an already unstable world. Recent psychological studies suggest that some people are profoundly stimulated by exposure to sadistic films and literature. In such a case, prudence dictates that we ignore the assumed rights of privacy and do our best to eliminate the sources of contagion.

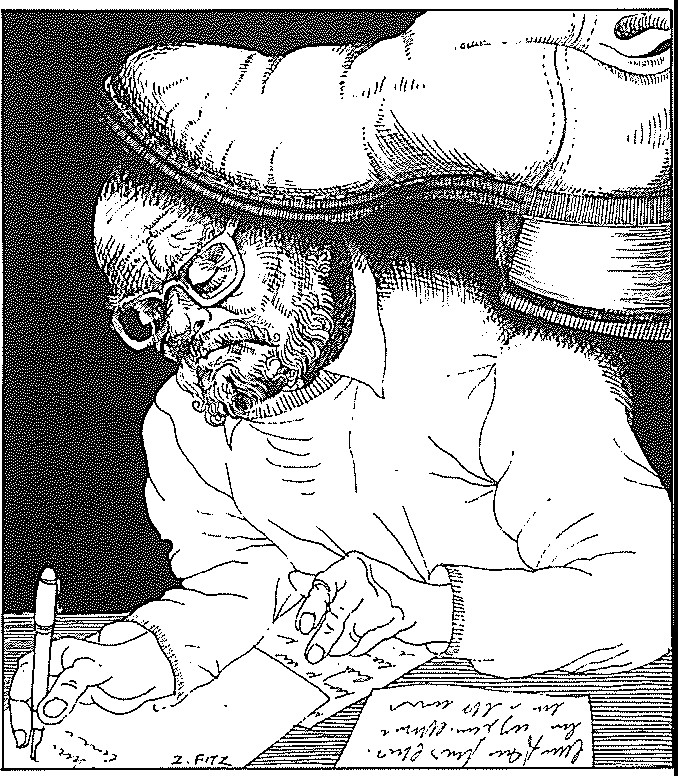

One final point. Americans seem unwilling to exercise the legitimate powers of the censor through their institutions.The fact that even conservatives (with the exception of George Will) fall back on the language of rights indicates a failure of nerve at the very center of our common life. Who are we, as Americans, and what do we live for, if we cannot put a stop to the prostitution of children and the exploitation of women who could be our sisters and daughters? In 1873 James Fitzjames Stephens made what he thought was an effective reductio ad absurdum of John Stuart Mill’s defense of natural liberty: if a group of men were to form an association to distribute literature which undermined the morality of women, we would not be inclined to listen to their pleas for freedom of speech. Stephens took it for granted that we would know how to deal with them. It’s taken only a century, but the hell of it is that we no longer know.

Leave a Reply