Nature imitates art: so Oscar Wilde instructs us. Whether or not natural sunsets imitate Turner’s painted sunsets, surely human nature is developed by human arts. “Art is man’s nature,” in Burke’s phrase: modeling ourselves upon the noble creations of the great writer and the great painter, we become fully human by emulation of the artist’s vision.

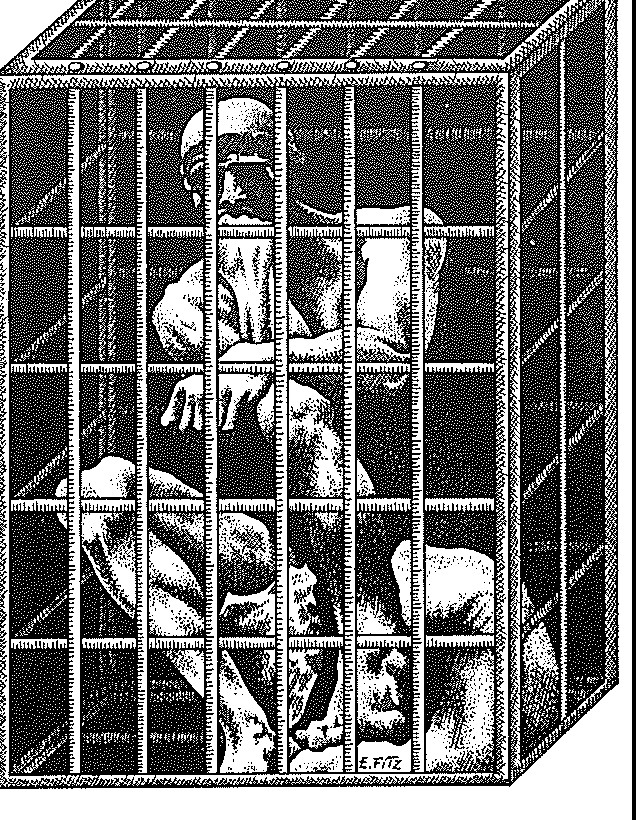

Or such is the upward way. But also there exists the path to Avernus, the way of degradation. The art of decadence and nihilism, the art of meaningless violence and meaningful fraud, presents us with the image of man unregenerate and triumphant in his depravity. Many in our time are seduced into the abyss of the diabolic imagination, taking for their exemplars the creations of the writers and the artists of disorder.

In our time, the disciplines of humane letters and of scholarship are disputed in a Debatable Land by the partisans of order and the partisans of disorder. In this clash, often the enemies of the permanent things gain the advantage. Yet their victory is Pyrrhic: for in undoing order, they undo themselves. Preferring to reign in Hell rather than to serve in Heaven, they make a Waste Land, and are condemned to dwell therein. In Burke’swords: “The law is broken; nature is disobeyed; and the rebellious are outlawed, cast forth, and exiled, from this world of reason, and order, and peace, and virtue, and fruitful penitence, into the antagonist world of madness, discord, vice, confusion, and unavailing sorrow.”

The frontiers of that antagonistic world of the rebels against nature and art have been extended, figuratively and literally, in our day; and many innocents have fallen trophy to the enemy. The antagonist world of disorder breaks into many a public library, where masses of the latest paperbacks of salacity and violence are offered to boys and girls–at racks just within the doors. Through fanatic politics, the antagonist world lays waste order and justice and freedom: a Pol Pot, having spent sufficient years in Parisian cafes absorbing Marxist dogmata, returns to Cambodia to slaughter a third of the population of his own country. Ideas do have consequences. Somewhere in the pages of Sainte-Beuve we encounter the revolutionary playwright who gestures from his window toward the ferocious mob pouring down the boulevard: “See my pageant passing!”

Richard Weaver knew this hard truth that our bent world cringes under the blows of the literature of disorder. As he wrote in Modern Age, a quarter of a century ago, “The intent of the radical to defy all substance, or to press it into forms conceived in his mind alone, is…theologically wrong; it is an aggression by the self which outrages a deep laid order of things. And it has seeped into every department of our life.”

The literary nihilism of our age has assaulted the dignity of man, the human state of being worthy. Five centuries ago, Pico della Mirandola declared that God has said to man, ”We have made thee neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, so that with freedom of choice and with honor, as though the maker and moulder of thyself, thou mayest fashion thyself in whatever shape thou shalt prefer. Thou shalt have the power to degenerate into the lower forms of life, which are brutish. Thou shalt have the power, out of thy soul’s judgment, to be reborn into the higher forms, which are divine.”

The literary nihilists, the artists of disorder, enjoin us to degenerate into the lower forms of life, which are brutish. One may discern in any day’s newspaper some item that is evidence of a widespread “intellectual” hostility toward religious belief and toward true humanism. Leading book publishers puff up works of fiction meant to convince us that indeed we are but naked apes, and works of political polemics intended to repudiate our social order and bring on, at best, what Tocqueville calls “democratic despotism.” Reviewers simper at the obscene and revile intemperately–or ignore altogether–books that attempt to work a renewal of mind and conscience. The oligarchs of the antagonist world, in the realm of letters, are eager to attract more dupes.

Pandering to literary and social decadence has its material rewards, even if the iron enters into the souls of such artists with an eye for the main chance. The emoluments of pornography are sufficiently obvious; few trades in our time are better paid. Ideological servility in letters also earns its ounce of gold at the devil’s booth. T. S. Eliot put this urbanely in his Criterion review of books by Leon Trotsky and V. S. Calverton, in 1933:

It is natural, and not necessarily convincing, to find young intellectuals in New York turning to communism, and turning their communism to literary account. The literary profession is not only, in all countries, overcrowded and underpaid (the few overpaid being chiefly persons who have outlived their influence, if they ever had any); it is embarrassed by such a number of ill-trained people doing such a number of unnecessary jobs; and writing so many unnecessary books and unnecessary reviews of books, that it has much ado to maintain its dignity as a profession at all. One is almost tempted to form the opinion that the world is at a stage at which men of letters are a superfluity. To be able therefore to envisage literature under a new aspect, to take part in the creation of a new art and new standards of literary criticism, to be provided with a whole stock of ideas and of words, that is for a writer in such circumstances to be given a new lease on life. It is not always easy, of course, in the ebullitions of a new movement, to distinguish the man who has received the living word from the man whose access of energy is the result of being relieved of the necessity of thinking for himself. Men who have stopped thinking make a powerful force. There are obvious inducements, beside that–never wholly absent–of simple conversion, to entice the man of letters into political and social theory which he then employs to revive his sinking fires and rehabilitate his profession.

So, 50 years gone, Eliot wrote of “Marxist criticism”–a term which, when uttered a few years ago at a literary congress in Budapest, was received with roars of derisive laughter: “Marxist criticism! Marxist criticism!” Yet in 1984, here in America, judgment of letters and scholarship in the light of ideological prejudices remains an effective weapon in the hands of the critical Rhadamanthus of the antagonistic world. Christian belief especially is detected and denounced by that Rhadamanthus: for the ideologue recognizes in Christianity, however enfeebled today, the chief power of resistance to the assault upon the dignity of man.

Yet there endures the literature of dignity and the scholarship of wisdom. It will take bettermen than Trotsky and Calverton to refute Plato, Vergil, Dante, Spenser, Johnson, and Eliot. “The dead alone give us energy,” says LeBon, and those dead men of letters and learning abide with us still. So long as some young people still are introduced to the imagination of such as Walter Scott or NathanielHawthorne—as I was atthe age of seven—the moral imagination will be nurtured. (Our public schools, however, are more willing to present the rising generation with the dully relevant.) The principal poets of the 20th century have been defenders of the permanent things: Eliot, Yeats, Frost. Our better historians have been men of spiritual perceptions: Christopher Dawson, Martin D’Arcy, Herbert Butterfield. Our keener literary critics have set their faces against the antagonist world: Allen Tate, Donald Davidson, C. S. Lewis. Our more influential novelists have been men attached to tradition: Evelyn Waugh, William Faulkner, and Anthony Powell, honored here today. Everyone present will think of other worthy exemplars of the literature of order in the soul and order in the commonwealth; but I am not compiling a catalogue.

With the exception of Mr. Powell, I have mentioned men of learning and letters who have entered upon eternity. Permit me to add the names of senior writers and scholars in a variety of disciplines who still are with us in the flesh and are worthier of today’s Weaver Award than is your servant: Eliseo Vivas, Andrew Lytle, Eric Voegelin, Malcolm Muggeridge, Gerhart Niemeyer. And, with Burke, I attest the rising generation: out of the renewed hopes of this country will emerge writers and scholars ready, in Pico’s words, to “join battle as to the sound of a trumpet of war,” assailing the vegetative and sensual errors of the age.

Order in society may be renewed through order in humane letters and order in scholarship, God willing. Two old friends of mine, laboring in a hostile climate of opinion and straitened in their means–T. S. Eliot and Richard Weaver–woke the imagination and the right reason of the better minds and consciences of this era. Future Ingersoll Prizes will recognize courageous and talented adherence to those enduring principles which Eliot and Weaver expressed so memorably, and which Solzhenitsyn maintains today.

I conclude, ladies and gentlemen, with a passage from a book to which I wrote the Foreward: Richard Weaver’s Visions of Order: The Cultural Crisis of Our Time, published just 20 years ago.

Literature is the keystone of the arch of culture. Not only is it the mostvarious,searching,and’complete’oftheforms,butit is the form in which an intellectual culture stores the ideas from which a society derives its rhetoric of cohesion and impulsion.Ifthisgoes,we cannot besurehowmuchelsewill be allowed to remain, and the degeneration of culture is the road back to brutishness.

There is always in cultural observance a little gesture of piety, a recognition that there are higher demands on man along with thelower….Then there is the further consideration that a culture is a protection against fanaticism both of the political and the religious kind. If there is nothing but a vacancy between men and their political or religious ideal, the response to this may be without the rationality and grace of measure….Thus art and manners are seen to have a relation to politics and religion, not teaching them in any simple or direct sense, but providing a bridge by which one is helped to pass from one kind of cognition to another. This is the highest reason of all for desiring to preserve the basis of our culture, which we have now seen to be threatened by pseudoscientific images of man.

Amen to that. Through Augustine of Hippo, the literature of order passed from the ancient world to the Christian world; and on the darkling pain of our own time of troubles, let us pray, there will stand firm men of letters and scholarship capable of expressing in ethical rhetoric those truths which seem scandalous to the nihilist and the ideologue.

Leave a Reply