The way foreign-policy mavens in Washington, D.C., talk about Afghanistan, you would think that country had successfully launched a ballistic-missile attack against us on 9/11. We have occupied Afghanistan for over 17 years now, but still we cannot leave because the Taliban could then return to power and once again grant haven to terrorists who might attack us. The obvious problem with this claim is that terrorists who might attack us can operate nearly anywhere, yet they only have the opportunity to attack us if we let them get past our borders.

Afghanistan could host a million Al Qaeda fanatics and pose little danger to us if we never let them anywhere near our land or our people. But border security and defense of our own citizens are simply not priorities for policymakers who instead dream of upholding a “liberal world order” and pursuing a strategy of planetary “openness.”

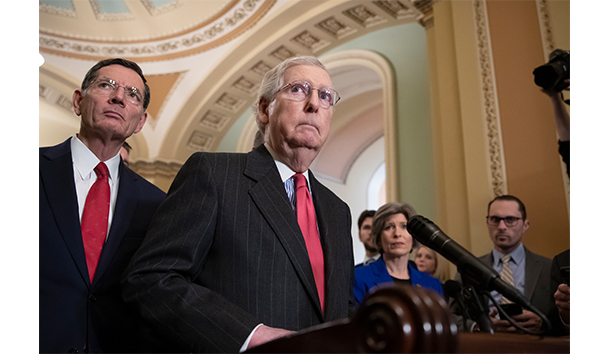

The unelected “influencers” and swamp creatures of Washington’s think tanks and lobbying outfits are only being true to their own institutional mission when they insist upon an American empire. They have no shame. But Congress is another matter: Its commitment to perpetual war is a betrayal of its responsibility to the public. That betrayal was dramatized February 4, when the Republican-controlled Senate voted 70-26 for a resolution opposing “a precipitous withdrawal” of U.S. forces from Syria and Afghanistan. After 17 years with little to show following the initial toppling of the Taliban, Republicans like Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Marco Rubio, Lindsey Graham, Ben Sasse, and Tom Cotton consider an exit “precipitous.” They ought to tell the American people what timeline they imagine would not be precipitous. Thirty-four years? Fifty? One-hundred?

The honor roll of Republicans who voted against perpetual war consists only of Rand Paul, Mike Lee, Ted Cruz, and John Kennedy. A majority of Democrats as well as Republicans voted for the resolution, though interestingly most of the party’s presidential aspirants—Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Bernie Sanders (nominally an independent senator)—opposed it. Therein lies a tale: Whatever their personal convictions might be, these ambitious senators recognize that the American public is not nearly as supportive of open-ended war as the majorities of both parties in the Senate are. Simply put, it’s easier to be a warhawk in Congress than on the presidential campaign trail. Note how often even the presidents who have taken the country into war—from Woodrow Wilson to George W. Bush—campaigned as candidates who would keep the country out of it.

Because the president is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, critics of an adventurous foreign policy have often placed their hopes for restraint in the legislative branch. Experience shows these hopes are usually misplaced. Far from being a restraint on presidential warmaking, the Congress is more often an accomplice or indeed a would-be instigator of conflict, though senators are reluctant to take responsibility for their bellicose views by formally declaring most of the wars they want other Americans to fight.

Our country suffers from a quirk of constitutional history: At the time of the Constitution’s drafting, Britain provided a model of a government in which the executive—the king—remained nominally the commander-in-chief, while real responsibility for war and peace lay with the legislative branch, Parliament. That Parliament bears full credit or blame for Britain’s foreign policy is today all the more obvious: It is impossible for a prime minister to go to war without the backing of a parliamentary majority. But here in the United States, the fact that the president does not depend on a legislative majority for his office means that legislators can have it both ways: They may pose as tough on the country’s enemies—or the enemies of any particular lobby or interest group or ideological sect—without having to bear any responsibility for the actual implementation of foreign policy. If a president does not go to war, congressional hawks may claim to be braver than he is. If a president goes to war and it turns out badly, the hawks in Congress can claim their motives were noble but the man in the Oval Office just happened to be incompetent. And if the White House and one or both houses of Congress are controlled by opposing parties, the temptation for irresponsible legislators to claim that the president is falling short in defending the country and its interests is nigh irresistible. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb might say, Congress has “no skin in the game” of war and peace. And senators and representatives are easily influenced by narrow interests and factions. Presidents are hardly immune to such influence, but they are subject to a wider public pressure as well.

This is yet another invaluable lesson in government taught by President Trump. The only hope for seriously reforming American foreign policy lies with a President who rejects the war-loving unwisdom of Washington, D.C., and who employs all of the power of his office—to a greater degree than Trump himself has so far been able—to imposing peaceableness on an irresponsible and grandstanding legislature. In American political reality, peace begins and ends with the president.

Leave a Reply