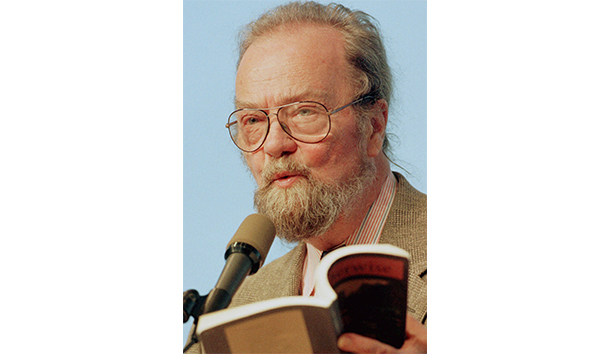

A long and distinguished literary career ended on June 23, 2018, with the death of New England poet Donald Hall. A versatile and prolific author, he served in 2006-07 as poet laureate of the United States. Like Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, and Richard Wilbur, fellow poets who settled in the region (though very different from one another), he was fundamentally sane and decent, differing thus from countless high-profile contemporaries in all the arts who have exploited base instincts and taken pleasure in aesthetic and moral destruction. Hall showed how reason and beauty, along with goodness, were not only compatible in literary art but its very essence. Billy Collins wrote of him as belonging “in the Frostian tradition of the plainspoken rural poet.” Liam Rector said that Hall lived “deeply within the New England ethos of plain living and high thinking.”

Hall died in Wilmot, New Hampshire, at his farm, Eagle Pond, which had been in his family since the 1860’s. Following in the broad streambed of the early Modernists, he eschewed their most exaggerated and arcane trends. Even an atypical poem such as “Without,” a parable on disease in somewhat delirious free verse, without punctuation and capitalization, is not only clear enough; its idiosyncrasies are part of its meaning. He displayed great poetic versatility, illustrating a range of forms, from rhymed stanzas to haiku and blank verse, and varied diction and tones.

Hall was born in Hamden, Connecticut, in 1928. He became attracted to literature upon discovering, at age 12, the work of Edgar Allan Poe. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard, where he became acquainted with George Plimpton, Robert Bly, and poet Adrienne Rich, at Radcliffe. Subsequently, he earned a B. Litt. from Oxford, spent a year at Stanford studying with the important critic and formalist poet Yvor Winters, and returned to Harvard as a fellow before accepting an appointment at the University of Michigan, where he taught for 18 years. He served as poetry editor for Plimpton’s Paris Review; in that capacity, he interviewed major literary figures, including T.S. Eliot.

Hall’s first collection of verse, Exiles and Marriages, appeared in 1955; his last (of more than 20), Selected Poems, in 2015. (A cycle of songs he read for recording in 2018 remains unpublished.) He also wrote fiction, criticism, biographies, and children’s books, among them the popular Ox-Cart Man (1979). He published textbooks and edited, alone or with others, anthologies that have become standard. Among the periodicals that published his book reviews was National Review (while Chilton Williamson, Jr., was books editor there). Devoted to baseball, and particularly the Red Sox, Hall wrote poems on the sport, such as “Meatloaf” (in nine stanzas), and even published articles on sports. Among the score or more of awards he received were the Frost Medal, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the Ruth Lilly Prize, and the National Medal of Arts. Additionally, he was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was an unrelenting opponent of the American war in Vietnam.

Perhaps he was best known, in his last years, for his 2005 prose volume The Best Day the Worst Day: Life With Jane Kenyon. This memoir recounts his marriage to his second wife, also a poet, born May 1947, and her battle against leukemia, of which she died in April 1995. She had been his student in writing at the University of Michigan. They married in 1972. Three years later they left Michigan and settled at Eagle Pond, where their life centered around domestic and country occupations as well as literature. They attended a local church. Today’s rather ghoulish reading public was greatly attracted by Hall’s account, both clinical and emotional, of the 18 months from Kenyon’s diagnosis to her death.

Interviewed in autumn 1991 by Peter A. Stitt in the Paris Review concerning creative writing curricula and degrees, Hall, very sensibly, underlined the drawbacks to such programs, which he had come to know at Michigan and have now multiplied many fold. Asked whether they had helped the cause of poetry, he replied that, while the attention paid to the genre in workshops and readings was not worthless, what he called the “industry” encouraged bad writing and amounted to a trivialization of literature and its misdirection toward other ends—jobs, credential-gathering, notoriety.

Although Hall’s writing is not always prim and understated, containing as it does intimate revelations and raw, indelicate elements, it provides generally a standard of what good poetry was in America in the 20th century and what it can continue to be now. Just read, and admire, in his Selected Poems, the short rhymed piece on birth and death, “My Son My Executioner,” or “Summer Kitchen.”

Leave a Reply