As I write, political factions left and right are sparring over the right approach to the coronavirus. I don’t envy President Donald Trump or the members of his coronavirus response team, for they appear to be in a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t situation. If they continue a general societal shutdown for too long, the economy will teeter on the brink of collapse, and the loss of jobs and ruin of savings may end up costing more in lives lost to despair than to the virus.

On the other hand, if Trump compromises with the economy and loosens restrictions, he can easily be blamed for the inevitable rise in deaths that would result. Judging the effects of one socioeconomic policy over another is inherently difficult, as French economist Frédéric Bastiat showed in his 1850 essay “Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas,” (“Things Which Are Seen and Things Which Are Not Seen”). The gist of his observation is that because socioeconomic policies are enacted in the real world and outside of the controlled conditions of a laboratory, it is hard to track the unintended consequences of any policy, or to say with certainty what would have happened if the government didn’t take this or that action to stop the virus.

Or, as the conservative English writer Peter Hitchens observed recently on Twitter:

Patient has pneumonia. Doctor says he will cure it by amputating patient’s leg. Patient recovers from pneumonia, (as he would have anyway) but now has only one leg. Doctor praises himself for success of his bold, radical treatment.

Better to be safe than sorry, and just take off the leg, I suppose!

This same rationale has been used time and again by the U.S. Federal Reserve and government officials to justify repeated bailouts for the banking sector and for the crony capitalist captains of industry who have their hooks dug deep into the halls of Washington, D.C.

In late March, we have an estimated $6 trillion in economic stimulus coming in the form of dollars flying off of the printing presses, with $2 trillion coming from Congress and $4 trillion in liquidity from the Federal Reserve. This does not include the massive “unlimited” quantitative easing (read: money printing) program promised by the Fed. The Fed has promised this easing program in the face of a global shortage of dollars as economies worldwide suffer from the effects of the virus, and as they have become dependent on U.S. dollar-denominated debt to finance their own profligate spending.

In his Mises Institute article “Why the World Has a Dollar Shortage, Despite Massive Fed Action,” Prof. Daniel Lacalle writes:

In the current circumstances and with a global crisis on the horizon, global demand for bonds from emerging countries in local currency will likely collapse, far below their financing needs. Dependence on the U.S. dollar will then increase.

However, just because the dollar may remain strong relative to other fiat money currencies doesn’t mean that there will be no negative effects on the U.S. population as their Federal Reserve plays the role of the world’s central bank. The monetary base will still expand, meaning that there will be, at the end of the day, more paper dollars out in the global economy chasing fewer goods.

In the meantime, whatever benefits there are from the Fed’s money printing are distributed unevenly, by those economic classes closest to the printing press. As Austrian School economist Murray Rothbard writes about the effects of monetary inflation in What Has the Government Done to Our Money? (1963):

The new money works its way, step by step, throughout the economic system. As the new money spreads, it bids prices up—as we have seen, new money can only dilute the effectiveness of each dollar. But this dilution takes time and is therefore uneven; in the meantime, some people gain and other people lose. In short, the counterfeiters and their local retailers have found their incomes increased before any rise in the prices of the things they buy.

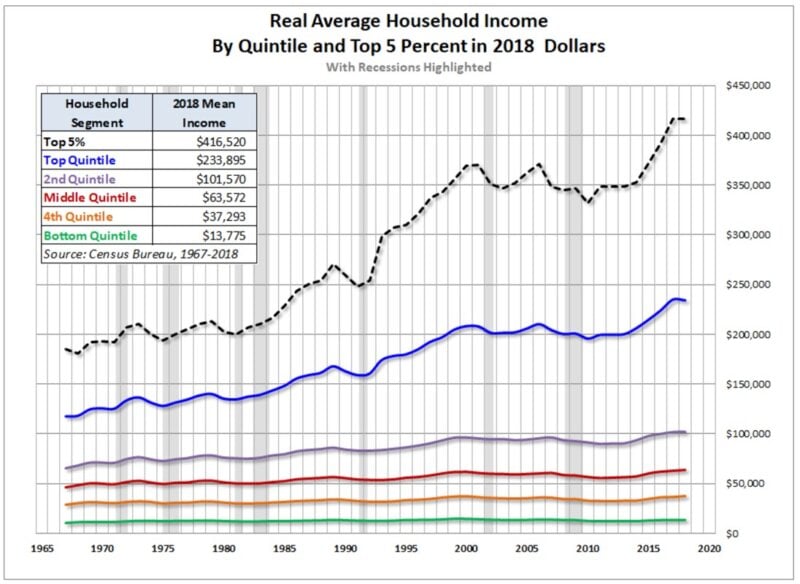

The Fed’s past interventions to prop up the economy by increasing the money supply have been reflected first in the price of financial assets, roughly 80 percent of which are held by the top 20 percent of the wealthiest U.S. citizens. By the time this extra paper money “trickles down” to the people in the lowest quintiles of the economy, the price of the goods they require to survive have risen to reflect this higher cost.

Economic specialists, of which I am not one, can probably credibly accuse me of oversimplifying this complex process.But the end results of the Federal Reserve’s rescues do not appear to be benefitting the average American. Printed here are charts that show the rising incomes over the past 50 years of that top quintile of wealthy citizens, which has decoupled from the rest of population that doesn’t hold nearly as much Fed-inflated financial assets. Real incomes for average Americans have stagnated even as their cost of living has increased, making them poorer than their parents or grandparents in real terms.

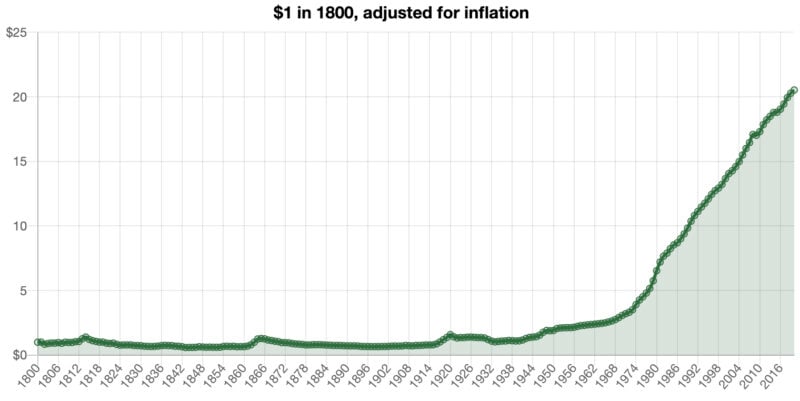

The next chart shows the purchasing power of the dollar since 1800. A dollar is now worth just 5 cents of its value then. Before the Fed was created, the dollar sometimes even increased in purchasing power as an industrializing America became a world economic powerhouse and shared the benefits with its citizens, rather than siphoning their saved wealth away through the stealthy tax of inflation.

The next chart shows the purchasing power of the dollar since 1800. A dollar is now worth just 5 cents of its value then. Before the Fed was created, the dollar sometimes even increased in purchasing power as an industrializing America became a world economic powerhouse and shared the benefits with its citizens, rather than siphoning their saved wealth away through the stealthy tax of inflation.

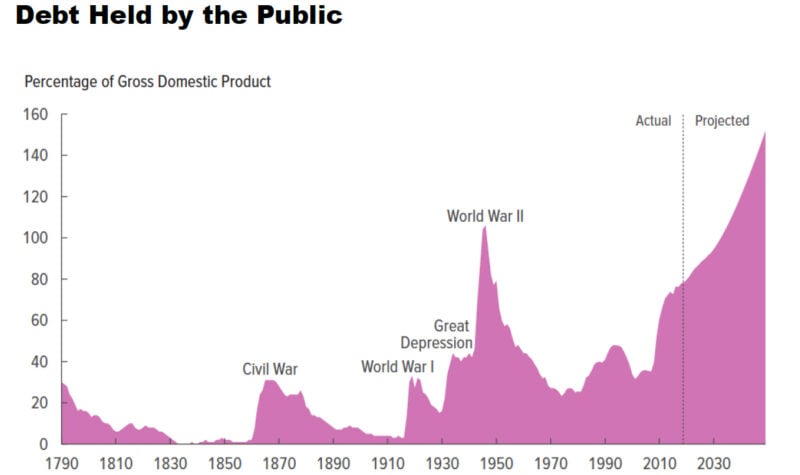

The final chart shows our public debt as a percentage of our economic output heading into the stratosphere over the next decades, set to eclipse the past peaks of World War I and II.

The final chart shows our public debt as a percentage of our economic output heading into the stratosphere over the next decades, set to eclipse the past peaks of World War I and II.

As Roger McGrath points out in his fascinating look at the Spanish Flu of 1918-19, (“Epidemic for the Record Books,” pages 44-45), during that national crisis, the public patriotically rallied on behalf of the nation, scrimping together its savings to lend money to the government to fight the war. Today, such displays of shared sacrifice are unnecessary; just Netflix and chill, as the government prints the money it needs at the expense of future generations.

So I don’t pay much attention to the furor over the president’s handling of the virus. As always, one political side will beat the drum and laugh while the other sulks; one will sob while the other sings; meanwhile the Fed will print, print, print.

Leave a Reply