Confessions of a Copperhead: Culture and Politics in the Modern South

by Mark Royden Winchell

Shotwell Publishing

298 pp., $19.95

Like the original Copperheads—those northern Democrat renegades who opposed President Lincoln’s war aims and were branded enemies of the Union—Mark Royden Winchell embraced the Southern cause as the “cause of us all,” to use the memorable phrase employed by Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens. Winchell wrote a number of books and many admirable essays—like those in this collection—which have kept alive the flames of the Copperhead legacy.

The author, who died in 2008, was born and reared in Ohio but resettled in the South after completing a doctoral degree at Vanderbilt—that erstwhile bastion of Southern resistance now largely overrun by woke academic carpetbaggers. There he studied under second-generation Fugitive-Agrarians, like Walter Sullivan and Thomas Daniel Young, and became a “naturalized hillbilly,” making the South his home for the remainder of his life. For most of those years, he wrote and taught literature at Clemson University, in South Carolina.

Winchell’s book is divided into two sections. The first makes brilliant and entertaining forays into political matters, including essays on the canonization of Martin Luther King, Jr.; on the liberal isolationism of Sen. William Fulbright of Arkansas; on the rise of the populist dynasty of Herman Talmadge, the Georgia governor who brought the New South to the Peach State and who, after his election to the Senate, became one of the stars of the Watergate hearings; on the trashing of Southern history in South Carolina at the turn of the present century, when the Confederate flag was dragged from the Statehouse dome by spineless Republican politicos who thereby exposed their lack of loyalty to something called “conservatism”; and, most importantly, on the long and acrimonious debate over Father Abraham’s true significance in the American story.

“Trashing Mount Rushmore” is a lengthy and colorful account of the evolution of what Winchell calls the “Lincoln anti-myth.” Of course, such an account necessitates some consideration of the Lincoln myth itself, beginning with Walt Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” (1865)—a far better elegy than Lincoln deserved—and later reaching its apotheosis in Carl Sandburg’s four-volume hagiography, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years (1939). This magazine’s readers will be well aware of the outlines of the myth, fabricated out of familiar shreds and patches: Lincoln the farm boy and rail splitter; Lincoln the tireless, circuit-riding prairie lawyer; Lincoln the devotee of the Union; and Lincoln the “Great Emancipator.” Fortunately for the reputation of “Honest Abe” in the eyes of his admirers, he was martyred while attending a performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s theater in 1865. The rest of the story is anything but history.

13’ bronze sculpture by Anna Hyatt

Huntington, 1963. (David A. Sonnenfeld /

State University of New York College

of Environmental Science and Forestry)

The Lincoln anti-myth is much closer to historical truth, and Winchell packages its development with admirable concision and an eye for the telling detail. The earliest of Lincoln’s detractors (aside from the Copperheads) were ex-Confederates, like Albert Taylor Bledsoe and the aforementioned Alexander Stephens. Their attacks did not gain much traction outside the defeated South, and even there, the tide of animosity directed at Lincoln had begun to diminish as Southerners became more enamored of the prospect of reunion.

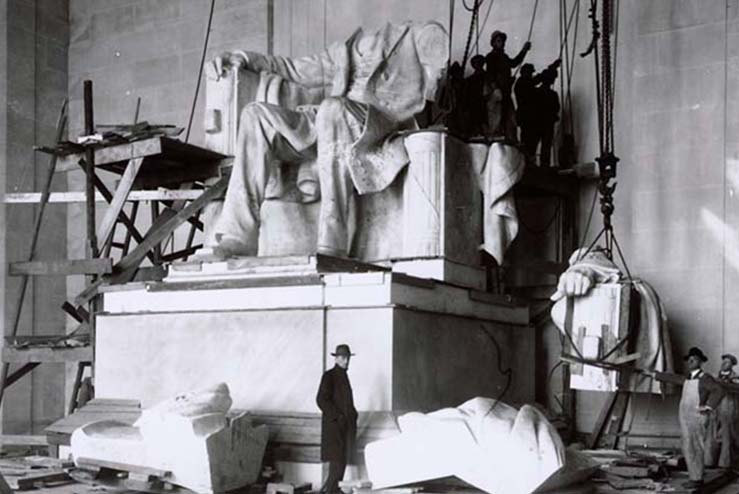

(U.S. National Archives /

via Wikimedia Commons)

But by the 1920s, H. L. Mencken, a journalist with a national reputation for brilliance and an enormous following, began to attack the Lincoln myth in the pages of the The Smart Set when he was editor of the magazine. Objecting to the “deification” of the slain president, he noted that Lincoln’s mythmakers had made an “obvious effort to pump all his human weaknesses out of him, and so leave him a mere moral apparition.” Regarding the Gettysburg Address, Mencken recognized how its beguiling rhetoric disguised a brutal truth: “The Union soldiers in that battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves.” They went to battle at Gettysburg as free men;

they came out with their freedom subject to the supervision and veto of the rest of the country—and for nearly 20 years that veto was so effective that they enjoyed scarcely more liberty, in the political sense, than so many convicts in the penitentiary.

After Mencken, it became almost respectable to question the Lincoln myth as well as the motives of the man himself. Among the themes that have been reiterated over the last century are those that involve Lincoln’s role in the increasing centralization of power in America, a process that in many respects he inaugurated, principally by trampling upon the sovereignty of the states, but also in his suppression of civilian dissent during the War—a point memorably made by Dean Sprague in Freedom Under Lincoln (1965). As Sprague and subsequent historians have confirmed, “More than 13,000 political prisoners were held in the various military prisons maintained by the Lincoln administration, [often] for months and even years without being charged with any crime.” Sound familiar?

It was, of course, the Copperheads who bore the brunt of that suppression. While the Lincoln myth has been in many ways deflated in recent decades, the notion of Union that the myth underwrote remains almost unassailable by either Republicans or Democrats, even as corporate globalism eats away at the quasi-mystical character it once possessed.

In the second half of the book, Winchell turns to literary matters, including treatments of John Steinbeck, M. E. Bradford, and Robert Frost. Of these, the essay on Frost is especially worth noting because it is not widely appreciated that the great New Hampshire poet was himself something of a Copperhead. While Frost’s poetry gives voice to a sensibility that is quintessentially that of rural New England, he was also a man profoundly devoted to localism, which allied him with the Southern Agrarians, whose work he admired.

In fact, Robert Lee Frost, born of a Copperhead father in 1874, was named after his father’s hero, Robert E. Lee, a fine Confederate general whose name has now been cancelled. Moreover, Frost established strong ties to several of the Nashville Agrarians, especially to John Crowe Ransom and Donald Davidson. Frost recommended Ransom’s first collection of poems (Poems About God) to publisher Henry Holt in 1919, and with both Ransom and Davidson, Frost shared a poetic affinity, since all three wrote poetry that “was both modern and formal”—very much against the grain of the period.

According to biographer Jay Parini, Frost was “an agrarian freethinker, a democrat with a small ‘d,’ with isolationist and libertarian tendencies.” For Winchell, Frost was simply an unconventional conservative, yet one who might not be recognized as such by those who claim the moniker today. He was a regionalist and a states’ rightist who was committed to “limited government [and] constitutional checks and balances.” While these are not “exclusively southern concepts,” notes Winchell, “no other region of the country ever went to war to defend those principles.”

Unlike some of his Agrarian confreres in Nashville (who saw the light soon enough), Frost saw no reason to celebrate the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932. He understood immediately that the old states’ rights Democratic Party had been captured by socialists. Like his father, Frost had strong political views, and wrote a fair number of political poems (which Winchell explores over several pages). Among these was the poem he famously read at the 1961 inauguration of John F. Kennedy. Struggling on that frigid, blustery day to read the poem he had prepared for the occasion, Frost eventually improvised and recited from memory “The Gift Outright,” a blank-verse composition of 16 lines:

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. She was ours

In Massachusetts, in Virginia,

But we were England’s, still colonials,

Possessing what we still were unpossessed by

…

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward,

But still unstoried, artless, unenhanced,

Such as she was, such as she would become.

The “land vaguely realizing westward” was, as Winchell and others have noted, an allusion to Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous 1893 lecture, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” which in turn no doubt inspired Kennedy’s campaign sloganeers. Yet the poem is clearly an affront to the bland idealism of the so-called New Frontier, with all its promise of a clean break from the past and with the land’s primordial claim upon those who would presume to conquer and settle it. The settlers pretended to possess the land but had not yet understood that to find a new identity as her people, they must in the end surrender, must become not possessors but possessed. As Winchell argues, “What was necessary to make this land America and ourselves Americans was a lived history.” We must be “wedded” to the land.

Behind the old poet on the podium were JFK, LBJ, and Richard Nixon, none of whom were likely to have understood that they were being gently mocked. Strictly speaking, of course, the poem is not political but philosophical, and Winchell returns to the theme in the final essay in this volume, “The Dream of the South,” in which he argues that “America’s official mythology has always been millennialist, which is to say we are a nation constantly seeking the Earthly Paradise.” After the Fall, he adds, the movement of civilization has always been westward. All too often America, after Columbus, was heretically depicted as a New Eden, the “Shining City on a Hill.”

The problem with such dreams is that they are fashioned only by discarding the problem of Original Sin. Forever seeking the Earthly Paradise, we “are apt to become dissatisfied with our more mundane terrestrial homes.” But southerners, Winchell asserts, were always less inclined to adopt this heresy. Their model has been not so much the New Adam as Odysseus, the hero who passes through hell “to return to a real home—complete with a middle-aged wife and a son he remembers only as an infant.”

(League of the South)

When Winchell died at the untimely age of 59, he was buried at Clemson’s “Memory Gardens.” He had long since regarded himself not only as a Southerner but as a South Carolinian, which is to say that he was happily possessed by the land. Would that the Palmetto State were blessed with 10,000 such happy traitors to the Union, since our native population has all but bartered away the courage of its own ancestors’ convictions.

Leave a Reply