Embarkation is the business of puzzling large weapons and vehicles, and the Marines that go with them, onto a ship that is run by a man who insists he does not have enough space for all that you need to take in order to do your job once he takes you where you need to go. Fitting four howitzers where three is a crowd is the most glamorous part of embarkation; the least is counting and issuing the sheets that your Marines inevitably will use to polish their boots or clean the deck of the berthing area once seasickness has set in. This is the good work that I was seeing to in August 1990, getting set to sail with my platoon from Okinawa to the Persian Gulf.

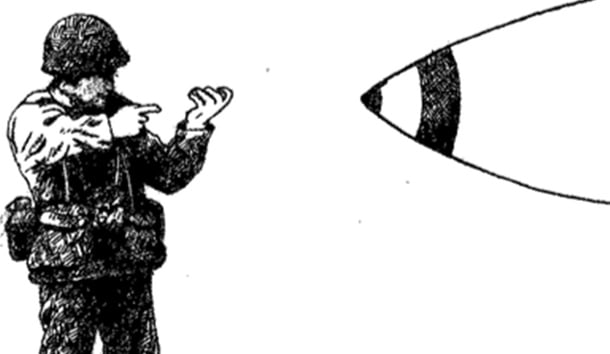

On the day the last truck was griped down, my battalion commander, the aptly named Lt. Col. Swords, called me to his office and handed me a copy of a Rudyard Kipling poem entitled “Snarleyow.” Snarleyow is a horse, the best loved of a team that is charging, cannon and crew in tow, into action. “When a tricky trundlin’ roundshot give the knock to Snarleyow,” the poor horse is “almost tore in two.” The driver cuts him free from the limber. In spite of his mortal wound, Snarleyow tries to follow after the cannon “as a well-trained ‘orse should do.” One of the crew, the driver’s brother, asks the driver to “pull up” for the wounded horse. The driver responds that he would not stop a charging gun even if the driver’s brother were wounded in action. In the next stanza, this ver)’ fate befalls the driver’s brother: He is mortally wounded, and the gun crew

saw ‘is wounds was mortil, an’ they judged that it was best.

So they took an’ drove the limber straight across ‘is back an’ chest.

The Driver ‘e give nothin’ ‘cept a little coughin’ grunt,

But ‘e swung ‘is ‘orses ‘andsome when it came to “Action Front!”

An’ if one wheel was juicy, you may lay your Monday head,

‘Twas juicier for the niggers when the case begun to spread.

The moril of this story, it is plainly to be seen:

You ‘aven’t got no families when servin’ of the Queen—

You ‘aven’t got no brothers, fathers, sisters, wives or sons—

If you want to win your battles take an’ work your bloomin’ guns!

Lt. Col. Swords said, “This is the sort of urgency you need to instill in your own cannoneers.” The poem is gruesome, but you can see why a young artillery officer would find it inspiring. I am not sure how battalion commanders keep their company-grade officers inspired today, when “Take an’ work your bloomin’ guns” is the least likely of dozens of orders America’s soldiers might hear. (In Somalia, it’s take an’ work your bloomin’ soup ladle; in Haiti, it’s take an’ prop up your petty thug dictator.) And I would rather not think about what poems officers might be giving one another these days, given the open mindedness of the Clinton administration. But it is clear that American military officers—and enlisted men—are becoming less and less inspired. They are leaving the service at the rapid rate of fire, and they are not being replaced. As Pentagon defense analyst Chuck Spinney observed recently, “the Army, Navy, and Air Force face the worst recruiting crisis in their history.”

This news is met with grimaces by the Bill Kristols, Robert Kagans, and Sen. John McCains of Washington, who are eager for America to take up the cause of “benevolent global hegemony”; but at the end of “The American Century,” for Americans who have grown weary of the White Man’s Burden, and certainly for America’s once and future adversaries, news of America’s shrinking—perhaps withering—standing army might be met with a smile. The American Armed Forces face a readiness crisis that very soon will make them unfit for the tasks the Kristols, Kagans, and McCains have in store for them. Their “imperial vision” will be an imperial hallucination.

A report from the U.S. Army’s Personnel Leaders’ Conference held in March paints a worrisome picture. Lt. Gen. Ohle, deputy chief of staff for personnel, states, “the number one issue in the Army today is shortfall of personnel.” Shortfall hardly describes it. Today, the Army is short 92 colonels, 251 lieutenant colonels, 408 majors, and more than 1,500 captains. (Note that there is no shortage of generals.) So severe is the shortage of captains that the Army has announced that “98 percent of First Lieutenants will be promoted to captain after 42 months of service.” (At one time, the system of military promotions was something of a meritocracy—the slogan was “up or out.” As one American politician has already observed, that slogan will have to be changed to “up not out.”) The Army has also sent a letter to all captains who have recently resigned their commissions, encouraging them to reconsider and promising “increased [and] faster promotions to the grades of Major and Lieutenant Colonel,” along with “schooling opportunities and multiple paths to career success.”

In the Army’s enlisted ranks, the news is much the same. Based on a dramatic failure to recruit soldiers in the first quarter of fiscal year 1999, the Army is predicting an enlisted shortfall of 10,000 by the end of the year. For the Navy, that figure was 7,000 last year. The services have not faced so severe a personnel crisis since Vietnam.

The news is not good for the Air Force, either. A message, dated February 1999, from Air Force Combat Command in Langley, Virginia, to Headquarters, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C., reports, “Air Force pilot retention continues to decline. The separation rate increased 9 percent in Fiscal Year 98 with”—this is alarming—”48 percent of eligible pilots opting to leave the service. Total Fiscal Year 99 pilot losses are expected to approach 2000. Additional losses are expected from post-bonus pilots.”

“Post-bonus” pilots have more than 15 years on active duty. The Air Force has long thought that, because they are so close to 20 years active duty (when they will be eligible for retirement at half pay and the full range of benefits), they no longer require incentives to keep them in the service. This unprecedented loss of post-bonus pilots raises at least two questions: Why are pilots who are so close to retirement getting out? And how shall we describe the readiness of the Air Force when it is losing so many of its most experienced pilots? Less than half of Air Force fighter pilots now fit the description “experienced” (at least 500 hours in the cockpit). Outside the fighter community, the situation is more grave: Only three in ten Air Force C-130 pilots, for example, are “experienced.”

The Air Force is predicting a total pilot deficit of 2,330 by fiscal year 2007. Where navigators are concerned, the picture is dramatically worse: By 2001, 54 percent of the fighter navigator force will be retirement eligible.” The February 1999 Air Force message describes air battle manager (ABM) retention as a “challenge”: ABM positions are manned at 72 percent, as are Air Force weather forecasters. In the tactical aircraft maintenance specialties, the Air Force reports not only personnel shortages but also “serious skill level imbalances.” Air traffic controller positions are currently manned at 69 percent; half of them leave the Air Force after their first term of enlistment is up. (I remember an extremely bright kid I ran into when I supervised the operations of the Enlistment Processing Station in Milwaukee. He had very high math scores, perfect scores on the electronic aptitude test, and wanted in the worst way to be an air traffic controller for the Air Force. He was sent packing when he admitted during his physical that he had had a bad reaction to a bee sting when he was 11 years old.)

The significant personnel attrition in the non-pilot specialties in the Air Force gives the lie to the argument that the Air Force is losing all of its officers to the commercial airlines. But, take heart, benevolent global hegemonists: The senior Air Force brass assure us that “Ideas on ways to increase retention are being explored.” Their latest idea, announced earlier this summer, is simply to forbid those personnel who are nearing the end of their enlistment or are due to retire, but are serving in specialties essential to the bombing of Yugoslavia, to leave the Air Force.

The recruiting prospects for the Navy are perhaps the worst of all the Armed Forces. According to Newsweek, “A recent Pentagon survey found that only 9 percent of young men between the ages of 16 and 21 were likely to consider joining the Navy.” But the Navy seems to have clearer ideas about how to solve its personnel crisis than the Air Force. The Navy believes it can fill its 22,000 vacancies in the fleet by luring sailors to sea with “more television sets on ship” and “shipboard e-mail.”

The Pentagon reaction—and the reaction from most American pundits and journalists—to these personnel shortages has been to blame our so-called booming economy, which offers a young man a better alternative than a military career. To believe this, however, one must assume that soldiers join up for the pay. There is little evidence for this. In fact, the one American service that has never sold itself as a place to earn great pay, or even as a place to learn job skills, is the Marine Corps. As you might expect, the Corps is also the one American service that is not suffering dramatic personnel shortages.

Ignoring this lesson, the Pentagon is lobbying hard to raise pay by as much as ten percent across the board. (Of course, this benefits admirals and generals the most, ranks in which there are no personnel shortages.) The Pentagon is also lowering standards. Weight and fitness requirements are being relaxed. Greater numbers of enlistees are being accepted without highschool diplomas. The effect? As one Army staff sergeant in Korea wrote to Chuck Spinney:

the bad news is that the Army is in a position where we will not be able to get rid of our duds. As the recruiting standards are lowered, the number of duds will increase. I hate to say this so bluntly, but we are almost in a position where we have to kiss privates’ a–es in order to maintain a certain manning level.

The material readiness level is no better. Everything, from jet planes to tanks, is routinely cannibalized for spare parts. Some defense analysts fear that the Navy is in danger of falling below 300 ships. (Remember Ronald Reagan’s 600-ship Navy?) The Air Force reports that, in fiscal year 1999, “aircraft and engine overhauls are expected to be 25 aircraft and 106 engines short of need due to lack of spare parts.” Grounding of Air Force planes for lack of parts is up more than 50 percent in the past decade, and, according to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Michael Ryan, stripping planes for parts has climbed 78 percent in the past four years.

Although senior Pentagon officials are quick to blame the material readiness crisis on the budget cuts of the Clinton administration, this explanation, much like blaming military personnel shortages on a robust civilian job market, does not withstand scrutiny.

Blaming a lack of bullets on a shrinking defense budget assumes that the Pentagon is spending its hundreds of billions of dollars wisely. After all, there is no shortage of military spending: On the contrary. President Clinton’s proposed fiscal year 2000 budget allocates nearly $300 billion for defense. The defense portion of the federal budget is greater than all the other portions of the discretionary budget combined; in fact, the United States spends more on defense than all of the other NATO countries (plus Japan and South Korea) combined, and more than Russia, China, and all of the “rogue states” (Cuba, Iraq, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Sudan, and Syria) combined.

Does the defense industry lobby have undue influence at the Pentagon? Chuck Spinney argues that part of the Navy’s potential ship shortage derives from the fact that perfectly good submarines are retired early to make room for the Seawolf and the New Attack submarine.

Marine Commandant Gen. Charles Krulak likes to tell the story of the young Marine who, when visited in his fighting hole in Kuwait by a U.S. ambassador, responded to the question, “If you could have something, what would you like to have?” with a hearty “Sir, I could use some more ammunition!” What Krulak does not say is that, not long after the Gulf War, the Marine Corps spent more money on family housing than it did on ammunition. That same year, the Corps spent more money on child-development centers than it did on spare parts. Another of Spinney’s correspondents, an Army NCO in Korea, describes a dramatic gas mask shortage:

A friend of mine at Camp Eagle told me that there is a shortage of protective masks; they have to borrow from other units when they go to the field. The rumor I heard about giving protective masks to family members is true. This is stupidity at its highest: bringing in protective masks for family members instead of evacuating the family members from a potential war zone. It would be cheaper to take the family members out of Korea. There would be no need for day care centers, schools, youth activities, or any of those cool things. The housing shortage would be eliminated. Of course, the wives would lose out on their opportunity to live like British colonialists in India.

The solution to the material readiness crisis is simple enough: Apply the logic of an infantry noncom and stop shoveling money into the gaping maws of our beloved defense contractors who push new weapons systems to replace perfectly good existing ones.

The personnel shortage may not be so easy to fix. There is almost no official discussion about whether the feminization of the American Armed Forces is causing good officers and troops to leave. There is even less speculation that soldiers are fed up with empire-building and OOTW (operations other than war). These OOTW have a debilitating effect on readiness even when they are not driving good men out. The more time a soldier spends in Somalia, or keeping the peace in Bosnia, or running the country in Haiti, the more time he must spend training to do his real job—kill people and break things—when he gets back home.

Kill people and break things. Take an’ work your bloomin’ guns. If America’s Armed Forces are called on to do either of these in some way that involves something more than dropping bombs from a safe distance on hospitals, embassies, and prisons—if our “brave men and women in harm’s way” are, in the near future, actually placed in harm’s way—Americans should brace themselves for a tremendous loss of life on the battlefield.

Two things, the first less likely than the second, could avert such a loss. America’s political leaders could adhere to “just war” theory; or America’s political leaders could confine their military adventurism to what might be called a secular version of just war theory-the “Weinberger-Powell Doctrine.” Weinberger-Powell presumes against war: Vital interests must be at stake; force is a last resort; crystal-clear objectives (including a solid victory) are required; the people and the Congress must support the action. Because our current war against Yugoslavia does not meet the Weinberger-Powell criteria, we should not hold out much hope for a resurgence of Saint Augustine’s ideas, either. If there is reason to hope that American servicemen will not be killed in large numbers in the next big conflict, it derives not from the likelihood that men of good morals and good sense will keep us out of fights that are not ours, but from the fact that, since the Vietnam War, America’s political leadership has been afraid to commit American forces wherever there is the least risk of significant loss of life. Recall how quickly we have pulled out of commitments at the first sight of blood in Beirut, Somalia, and elsewhere.

U.S. Army Reserve officer John Gentry made this very case in the Autumn 1998 issue of Washington Quarterly: “[I]n recent years the United States has extensively deployed military forces abroad, but America’s leaders are increasingly reluctant to use them in roles that could lead to casualties in combat.” Gentry, an unapologetic interventionist, fears this reluctance will

encourage us to become yet more isolationist: with bruised feelings and a sense of paranoia about attacks, we might retrench even more deeply—intellectually and physically. Perhaps we will find security for our troops, if not our national interests, in the American heartland. They would be home and safe, but there might not be much reason any longer to have them in uniform.

Every crisis has a silver lining.

Leave a Reply