It is hard to believe that only a few years ago, political economy was dominated by talk of zero-sum societies and the limits to growth. Today, the talk is all of job-creation, reindustrialization, and high-techinvestment. This reversal in outlook is one of the clearest indicators of the ascendency of right-wing themes in American politics.

The left has always been more concerned with redistributing the wealth that already exists than with creating new wealth. The early claim that socialism was more efficient than capitalism was quickly disproved in action and abandoned. The argument turned so that stagnation became the virtue of socialism. From Galbraith’s The Affluent Society to the wave of environmentalist tracts, economic growth was equated with at best waste and at worst the destruction of the human species. The 1970’s saw this attitude hit its peak. Per capita output at the start of 1981 was essentially the same as it had been five years earlier, and without gains in productivity, there can be no real progress in living standards. The public saw how a trend towards zero economic growth actually looked-higher unemployment, higher taxes, lower take-home pay, double digit inflation, and the erosion of strength compared with foreign competitors.

The welfare state is incompatible with economic progress. Progress depends on capital investment, both in research to create new technology and in equipment to embody it. Capital comes from saving. To finance the expansion of social services, taxes were levied most heavily on those individuals and businesses which produce the most savings. The savings pool was further reduced by deficit spending which converted capital into consumption. The separation of work and reward which is central to the philosophy of redistribution weakens incentives. The promotion of a hedonistic culture and the expansion of “rights” to immediate gratification undermined commitment to the long-term task of building for the future.

An economic theory more dangerous than socialism acted as the carcinogen. Keynesianism purported to be an objective explanation of how the economy worked and how capitalism could be saved from itself. As a theory it made little sense. Saving was a drag on the economy; capital was over abundant while investment opportunities were limited. Production was automatic, but people had to be coaxed into spending money. The entire process of economic advancement was turned on its head. The success of Keynesianism rested not on its economics, but on its politics. As Keynes himself observed, since private capital formation was now considered an impediment rather than a source of growth, “one of the chief social justifications of great inequality of wealth is, therefore, removed.” Those who wished to remove the capitalist class on ideological grounds could now proclaim that they were acting in the national economic interest and in accordance with economic science. Redistribution, deficits, and progressive taxes destroyed “excess” capital and increased aggregate demand. No one worried about where the goods would come from to satisfy this demand.

When the goods (and jobs) were not forthcoming and the increased demand merely pushed up prices, the Keynesian system collapsed. It is this collapse and the development of a new program to replace it which is detailed in Paul Craig Roberts’s book. Roberts, now a professor at Georgetown University, served as the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy, 1981-82. He had previously drafted the Kemp-Roth tax cut plan and fought in the vanguard of the supply-siders both on the staff of the Senate Budget Committee and as an associate editor of the Wall Street Journal. It is this fight to establish a new framework for policy which is chronicled. Along the way, Roberts gives one of the clearest explanations available of supply-side economic theory.

The supply-side revolution is associated with the Reagan Administration, but Roberts reveals the progress made in Congress in the years before Reagan’s election. Though Republicans were the innovators, it was a bipartisan movement with key Democrats like Russell Long, Lloyd Bentsen, and Sam Nunn providing openings. With the Democrats firmly in control of both houses of Congress, the supply-siders had to rely on their ability to persuade opponents to change their views. By 1979, the Joint Economic Committee had largely substituted supply-side ideas for Keynesian, and major victories had been scored in both the House and Senate Budget Committees. Roberts’s account of this struggle is one of the best parts of the book. Ideas do have consequences and reasoned argument can change minds even in an environment dominated by partisan politics.

Roberts places some distance between himself and Arthur Laffer, whose Laffer Curve became the popular representation of the supply-side idea. The Laffer Curve, by claiming that tax cuts so stimulated the economy that tax revenues would increase rather than decrease, aroused unrealistic expectations. When the budget deficit widened in the wake of the tax cuts, critics pointed to the Laffer Curve, proclaimed it (and by extension the entire supply-side idea) to have foiled. The Lafferites, in their enthusiasm, overran opponents who were concerned about deficits or cuts in spending programs by assuring them that tax cuts provided more funds than ever. The problem was that there was a time lag of several years between the cuts and the new flow of funds. The economy does not expand instantaneously. As Roberts points out, it took three years for the modest cuts of the Kennedy program to yield higher revenues.

The effects on the deficit of the Kennedy tax cuts were minimal because Federal spending was kept under control. Between 1960 and 1965 the budget increased by only $17 billion. Washington’s share of GNP fell between 1962 and 1965, the period following the tax cut. The tax base was expanding relative to Federal expenditures. In contrast, despite all of the talk about spending cuts, Washington took a larger share of GNP in 1984 than it did when President Reagan first took office. Annual spending 1981-85 has increased by over $270 billion. The supply-side tax cuts have opened the gap between revenues and expenditures, but more important is the gap opened between expenditures and the tax base of the economy. As long as spending remains out of control, deficits are inevitable unless taxes are in creased. The supply-siders are correct when they point to the dire consequences to the economy which would result from higher taxation. So what is to be done?

Throughout the book, Roberts emphasizes that the supply-siders are a political movement. He is critical of the GOP “establishment” which argued for “responsible” policies tying tax cuts to spending cuts. This strategy was politically unpopular, which to Roberts is more important than whether it was correct. Any attempt to cut taxes provoked opposition from those who feared that their programs would be cut. To break this, tax cuts were voted without threats to spending. This widened the deficit. Roberts argues, however, that deficits which result from tax cuts are not as bad as deficits which result from spending hikes because the tax cuts stimulate savings and investment. In short, deficits are bad, but the supply-side effects help to off set them. Keynesian deficits resulting from high spending without tax reduction create only bad effects.

Yet, this still avoids the central issue: the share of the nation’s resources taken away from productive activity by the government. Roberts concedes that the tax cuts did not generate enough new savings to finance the added debt. This means that there was a net drain of the capital market. The diversion of capital from the private sector to the national debt weakens the ability of the economy to grow. The tax cuts have not forced the govern ment to control spending, only to shift the method of financing that or, ending from taxes to debt-not a change for the better.

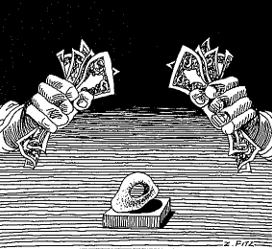

By downplaying the spending issue and the dangers of the deficit in conservative circles, the supply-siders have, unintentionally, made control of the budget harder to achieve. The political bias has always been toward spending (which is popular) and against taxation (which is unpopular). Liberals have used this to gain control over more of the nation’s resourcesthan the public would have allowed had the public been forced to pay for it openly in taxes. For the right to further separate spending from taxing in the public mind can only make matters worse. The people must have the control of the purse strings thrust backinto their hands whether they want it or not. The only way political pressure can be mustered to control spending is if the majority knows that it will have to pay for every new program out ofits own pocket. A “free lunch” of programs without taxes is irresponsible whether promoted by the left or the right. Roberts is right about the beneficial effects on the economy from lower taxes, but they must be accompanied by lower budgets brought into balance. That is why the next phase of reform must go beyond supply-side policy, towards a balanced budget Constitutional amendment. Within such a framework, the public must choose spending reduction or tax increases. Both the supply-siders and the economy should win that one.

“Although he is surely too serious-minded an ideologue to have planned it that way, Mr. Roberts’s book yields a description of the egos, power grabs and ambitions of the people involved that turns “The Supply Side Revolution” into a kind of old fashioned Western shoot-out set against a dismal background of economic policy making.”

The New York Times BookReview

Another issue that calls for a policy surpassing what the supply-siders have yet proposed is reindustrialization, one of several topics addressed by Felix Rohatyn in his collection of essays. Rohatyn is a senior partner in the investment banking firm of Lazard Freres. He has had experience bailing out the N.Y. Stock Exchange in 1970 and New York City in 1975 as a leader in both financial rescue operations. Though most often associated with Democratic candidates, he is considered a neoliberal willing to break with the past and adopt policies which reflect many of the concerns voiced by conservatives. This may be most obvious in his essay on the Polish debt. He advocated pushing Poland into default while severely restricting future loans to the Communist bloc. To Rohatyn, capital is a vital resource. Policy should concentrate on attracting investment here rather than letting capital flow to our enemies. When foreign operations of American banks conflict with the economic aspects of national security, the banks must yield.

This raises a contradiction which the right must face. As nationalists, conservatives want to maximize the country’s material strength, which depends on technology and the economic base. But as supporters of capitalism, conservatives advocate a “free market” even when that market ignores national borders. The contradiction occurs when the workings of the global market undermine the sinews of American industrial power.

Rohatyn describes manufacturing industries in trouble: Harshly affected by foreign competition, unable to raise vast amounts of capital needed to modernize, they live from hand to mouth, not investing in the future in order to survive today. They are also affected by a deep structural shift not only in regional prosperity but … in the basic nature of American work as well – the shift away from productive industry toward consumer and retail services.

The American economy has produced over six million new jobs in the last four years, but at the same time has lost over two million jobs in heavy industry. The economy can provide jobs, but it makes a difference what those jobs are. Firms which produce fast-food and financial-planning services do not contribute the same strength and balance to the nation as do steel mills, shipyards, and auto assembly plants. Nor do they redress the imbalance of payments since they neither produce exports nor replaceimports. In time, this shift can under mine living standards as low-pay, low productivity service jobs replace the high-pay, high-productivity jobs in manufacturing.

In the global industrial economy, there are very few free markets, no “natural” division of labor, and little harmony of interest. To operate as if there were such things is to allow the policies of other nations to determine what industries America will be allowed to keep (i.e. those industries no one else wants). “Certainly we need tax cuts and regulatory reform and a balanced budget,” says Rohatyn, but we need more. His suggestion is a new Reconstruction Finance Corporation which will supply capital to those in dustries our economy needs to main tain and advance. Not loans which would increase the burden of debt, but equity capital. Instead of destroying capital as government policy has been doing, the government would work to create capital.

Rohatyn is not talking about picking “winners” out of domestic competitors. He realizes that governments are not very good at this, nor do “winners” need such help. His aim is to save strategic industries from devastation by foreign competitors. There is probably no more traditional form of economic policy than this. It is called mercantilism, and has been the common practice of all Great Powers when facing strong economic rivals.

The U.S. had no such rivals imme diately after World War II, but times have changed. Conservatives pride themselves on being realistic. Utopian idealism and abstract theories are the obsessions of the left. “Free trade” was a concept adopted by English liberalism and used to justify the breakup of the Empire and the fall of Britain from economic supremacy. It is time for conservatives to ponder what category this theory really falls into. As Roberts says, there is a “weakness tax” paid as the world “exploits our loss of economic, military and diplomatic supremacy.” This “tax” will not be automatically repealed. Positive policies will have to be adopted to remove it. While many commentators have considered Roberts and Rohatyn to represent policy alternatives, we would be better served by adopting a policy synthesis of their ideas.

Leave a Reply