by Neema Parvini

Societas

234 pp., $29.90

The West, it is said, is modernity. But if it is, there is melancholy at its core. Our most confident centuries have subsisted in the shadow of Rome—our Ozymandian awareness that the greatest powers must pass, and all empires will be overthrown.

To a certain type of observer, Western decay seems obvious and often imminent. Like Daniel in the palace of King Baltasar, they are able to translate Mene into “the days of your kingdom are numbered.” Other opinionators are unable or unwilling to read the writing on the wall. Even today, except for concerns over climate change, there is a very human reluctance to arrive at logical conclusions from abundant data. Declinists are accused of “rosy retrospection,” but optimists are at least equally guilty of “pink projection.”

In Prophets of Doom, Anglo-Iranian academic Neema Parvini discusses 11 critics of contemporaneity. Parvini is an energetic and (to borrow Baltasar Gracián’s expression) “dis-illusioned” discussant, unsentimental about human nature, scornful of pabulum, and armed with mordant wit. He has rendered a considerable service to intellectual history by summarizing and comparing often unappetizing yet obviously urgent writings, providing a convenient conspectus of declinist thinking. It is simultaneously a service to the future, offering timeless counterweights to today’s cognitive biases.

The oldest of his eclectic 11 subjects is Giambattista Vico, born in 1668. The others are obvious inclusions—Thomas Carlyle, Arthur de Gobineau, Brooks Adams, Oswald Spengler, Pitirim Sorokin, Arnold Toynbee, Julius Evola, and John Bagot Glubb. Joseph Tainter and Peter Turchin are still with us. Some chapters end abruptly, but this is a question of style rather than substance, judging from the extensive bibliography and copious endnotes.

It requires character to stand against fond delusions, and those who did (or do) deserve to be honored. As Spengler noted in Man and Technics, “Optimism is cowardice.” The author aims for “value-free” analysis, but his heart belongs to the pessimist party. He tosses and gores Tony Blair’s famous, fatuous 2005 assertion that liberal globalism was the irresistible wave of the future:

The End of History did not materialise and will one day be regarded as a self-contained epoch that started in the direct aftermath of 1945 and will end at some point in the future, during which some great things were achieved and during which most educated people took leave of their senses.

Leaving this fast-decomposing corpse on the field, Parvini rides with relief to 200-118 B.C.—the lifespan of Polybius, a Greek historian of Rome, whose Histories systematized earlier intuitions about civilizations’ trajectories. To Polybius, states were organic but bound by ineluctable laws of politics and psychology. Monarchy under charismatic strongmen is mankind’s natural state, to be succeeded by hereditary monarchy, which degenerates into tyranny, then aristocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and ochlocracy—after which the cycle recommences with the emergence of a new charismatic strongman. Polybius’ Anacyclosis influenced contemporaries like Cicero and Livy and was rediscovered by Renaissance scholars and then by Vico. We can trace in Polybius a future cliché: “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. Weak men create hard times.”

The taproots of progressiveness are in the Bible. Medieval Christianity was realistic about what could be done with Man. But millennialists were swayed by the neat purposefulness of Genesis-tribulations-uplift—the didactic and “happily ever after” qualities inherent in the greatest stories. As belief in Original Sin and God’s existence have retreated, the whole cosmos has become “Caesar’s,” and all that is left for the meaning-starved are old habits of dualist thinking and blind belief in future bliss.

wikimedia commons)

Vico’s 1725 New Science set out shrewd objections to what he saw as anti-social new notions—shallow rationalism, the mechanistic implications of natural laws, and the selfishness of social contracts. He preferred “poetic wisdom” to sere analysis, and thought Homer a better guide to Greece than any philosopher. He found few readers in his lifetime; Parvini gives a vignette of the scrawny scholar slinking through Naples, his home city, avoiding people to whom he had sent his manuscript, who “give me not the faintest sign that they have received it, and … confirm my belief that it has gone forth into a desert.” He was only catapulted into consciousness in 1939, in an unlikely fashion, when James Joyce used New Science to structure Finnegan’s Wake.

He is interpreted today as an intuitive understander of how societies are made and how society-specific “truths” are arrived at—a “social anthropologist” before social anthropology, a “relativist” before relativism, a “post-modernist” even before modernity had fully arrived. He also believed that societies could improve. But he felt improvements carried seeds of their own destruction, as a mythic “Age of Gods” becomes an “Age of Heroes” and eventually a hubristic “Age of Men,” when poetry becomes prose and romance reason, and individualism makes everyone an island.

wikimedia commons)

Carlyle was his century’s skeptic-in-chief, thundering magnificently against complacency and sentimentality. He was hugely influential; he was also abrasive and seen as excessive and unduly gloomy. Even a friend, Edward Fitzgerald, complained “Carlyle raves and foams, but has nothing to propose.” Carlyle lost his faith when young and always felt that lack. He yearned for primordial forces of “Love, and Fear, and Wonder, of Enthusiasm, Poetry, Religion, all of which have a truly vital and infinite character.” He hated democracy, but even more, the middle-class money-counters and moralizers who preached equality and liberalism but left the poor to be ground down by the “Age of Machinery.” He loathed industrialism (his word) yet saw possibilities in great entrepreneurs who might translate “hard energy” into action and become “Great Men” capable of restoring a hierarchical and mystical pre-rational order.

wikimedia commons)

Arthur de Gobineau is today written off as an ur-racist, the originator of Aryanism through his 1855 Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaine. His dislike of leveling was partly personal, but Parvini also suggests that his meaning has been lost in translation. By replacing his unscientific “racial” categorizations (white, black, yellow) with “poetic” categorizations denoting different aspects of the human spirit (chivalric, primal, practical), Parvini shows him in another light. In the 19th century, “race” was a generic term applicable to any discrete group, so Parvini’s suggestions seem closer to Gobineau’s intention. The “miscegenation” Gobineau decried, so alarmingly to our ears, was really a cultural coarsening, as the “chivalric” spirit was diluted through intermingling.

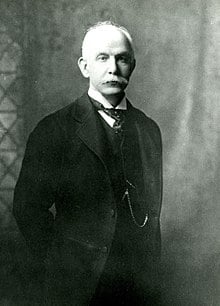

wikimedia commons)

Brooks Adams was an American Brahmin and deeply engaged in public life; he influenced President Theodore Roosevelt. But his prickly personality and lugubrious views put him at odds with excitable Americans: first, the poet Walt Whitman and then President Woodrow Wilson. Boosterish Americans who had “won the West” and would soon be entering “the American century” were not drawn to one who foresaw America’s downfall and dichotomized civilization into two unappealingly named phases: an “Age of Fear” and an “Age of Greed.” Adams favored “Fear,” meaning awe and energy, but worried it was outmoded in the era of centralization and cheapness. He did not even offer the distant comfort of cycles, believing there were no more barbarians to refresh the Western world, and so ultimately Asia would rule.

wikimedia commons)

Oswald Spengler’s 1918-1922 Decline of the West likens cultures to plant species, each with a unique symbology and “high history,” each rooting, fruiting, and dying in its own way—a Nietzschean endless return, “a drama noble … and aimless as the course of the stars.” Modern civilization is a late phase in the cultural life cycle, when the plant has already passed its zenith. For Spengler, Europe’s “Faustian” spring was the Gothic Middle Ages, followed by a Baroque summer, an Enlightenment autumn, and finally, a bitter winter dominated by leveling and money-making. Only “Caesars” could overthrow the enervated accountant class; “blood” must defeat “money” so Europe could slake its soul. This poetical thesis found fertile ground in postwar Germany, and helped feed fascism, even though Spengler himself was dead by 1936 and the Third Reich suppressed his writings.

wikimedia commons)

Pitirim Sorokin was the first to conduct an empirical and statistical survey of other cyclical theorists, to come up with a similar division of civilizations into “ideational,” “sensate,” and “idealist” phases. Arnold Toynbee devoted 21 years to his Study of History, whereby civilizations prospered or decayed depending on how they handled threats, attracting opprobrium by observing the deleterious effects of democracy, which included the greater brutality of modern wars. He slowly shifted position, concluding that Christianity could avert a collapse.

commons)

Joseph Tainter’s 1988 The Collapse of Complex Societies sees decline economically. As societies become larger, they require ever more resources and administration. Bureaucracy burgeons and bills soar, and once states stop expanding, the cost of control cuts more deeply into national margins. Parvini is more admiring of Peter Turchin, whose “Metaethnic Frontier Theory” borrows from the 14th-century Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun’s concept of asabiya (collective solidarity) to show how highly motivated marginal groups can capture entrenched states that have lost the habit of collective action. His cyclical thinking derives from his “Demographic-Structural Theory,” which posits that an increase in population leads to instability and war, which decreases population, which restores stability, which restarts the cycle again by increasing population.

wikimedia commons)

Julius Evola is notorious as the éminence grise for the radical right—a monocled mystagogue who clouded his life deliberately in obscurity and wrote compulsively on esoteric and metapolitical themes. Parvini peels away Evola’s “Fascist” notoriety to find a traditionalist believer in inexorable cycles and transcendence and the “truthfulness” of myth. Evola was an opponent of both communism and capitalism, which in different ways represent the utterly anti-human “reign of quantity.”

wikimedia commons)

Evolan esotericism would have been Greek to John Bagot Glubb (“Glubb Pasha”), the bluff British soldier who led the Arab Legion in Transjordan from 1939 to 1956. Glubb used his Arabist expertise and experience of British imperial retreat to postulate a general theory of civilization in two short 1978 works, The Fate of Empires and The Search for Survival. Vigorous nations become empires, but these only persist for 200 to 250 years before “liberal sentiment” leads to disintegration. Self-sacrificing conquerors metamorphose into insulated intellectuals, who eventually reason themselves and their societies into what Jean Raspail called “deadly doubt.”

Like most of the “prophets of doom,” Glubb also believed that cultures are essentially incommunicable, which has clear implications for societies aspiring to be “multicultural” (which is in itself a sign of waning confidence). But the doom prophets would also agree that any people may have its turn if fortune favors them, which behooves a truly expansive view of all peoples and all great men.

Parvini’s doom prophets, for all their occasional excesses, sometimes seem more humane than today’s noisy “humanitarians.” They insist that our societies shouldn’t be so ugly, and that people deserve more fulfillment than they generally receive.

Leave a Reply