As a conservative “anarchist” and non-interventionist with anti-vocational views on education, Albert Jay Nock (1870-1945) can seem paradoxical. His influence was lasting and he took unconventional stances on many topics. He viewed conservatism as primarily cultural, anarchism as radical decentralization, education as a non-economic activity, and foreign policy as a noninterventionist endeavor.

Raised in Brooklyn and rural Michigan, Nock attended St. Stephen’s College and became an Episcopal clergyman in 1897. In 1909, he left his ministry, his wife, and two sons, and took up writing in New York, where he associated with Progressives, including Senator Bob LaFollette and historian Charles A. Beard, whom he counted among his friends. He served as associate editor of The Nation—a magazine founded in 1865 as an organ of liberal and later mildly progressive reform—as its editorial stance became increasingly critical of American wartime policies.

Along with Englishman Francis Neilson, a former Liberal MP, Nock founded the libertarian magazine The Freeman, which published from 1920 to 1924. Nock and Neilson favored American reformer Henry George’s “single tax” on rents, meant to foster genuinely free markets. Their publisher was B. W. Huebsch, a German-Jewish American who published works from a coalition of literary and political radicals, including a clique of German Americans recently hard-pressed by excitable patriots during World War I. Praised as featuring the best American writing, The Freeman showcased Nock’s political views and carried forward the political philosophy of the late Randolph Bourne, whose writing eloquently unmasked the predatory character of all States. Bourne adhered to American philosopher John Dewey’s “instrumentalism,” a variant of pragmatism in which rational techniques suffice to produce a better world, but he later rejected it when Dewey mistook the World War for a social reform project.

Multilingual as well as massively grounded in classical and European literature, Nock was among the best essayists of his age. After The Freeman folded, he wrote for The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and The American Mercury. His books include The Myth of a Guilty Nation (1922); Jefferson (1926), which historian Richard Hofstadter called “a superb biographical essay”; On Doing the Right Thing and Other Essays (1928); Our Enemy, the State (1935); and Memoirs of a Superfluous Man (1943).

Influenced by the German-Jewish sociologist Franz Oppenheimer, Nock saw the origins of the organized State in the conquest of peaceful peoples by barbaric nomads seeking tribute. The State was thus the organization of nomads and embodied their political means of acquiring wealth. The economic means—peaceful production and exchange—did not require the State, only “government,” which was both local and minimal. Here Nock uses the still-prevalent language of state-worshipping political scientists, but with the State as villain and government regarded as rather benign. History was thus a race between “State power” and “social power,” a theme expanded upon by his protégé Frank Chodorov, a noninterventionist Georgist and founder of the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists, now known as the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.

Nock’s ideas resemble the strain of American agrarian republicanism that presupposed widespread ownership of productive property from which local markets could arise without imperiling freedom. For Nock and Oppenheimer, the land question—who owns the land and how they got it—came first. Where States allocate available lands to a small minority, those favored monopolists then dominate a society whose members work for them. Nock argued it was this initial intervention of the State in the distribution of land that was the source of economic injustice, rather than Karl Marx’s critique of the primitive accumulation of capital, because State allocation of land entrenched mechanisms for further accumulation of land and capital. Nock derided Marx’s tunnel vision on this topic, especially since he believed that Marx came near the truth in volume one of Das Kapital in that book’s description of the origins of English land monopoly. When Nock wrote Jefferson and Our Enemy, the State, he mourned America’s failure to avoid the State’s corrupting effect over its economic system.

Like many Progressives, Nock endorsed the theories of Henry George, who also made land ownership and distribution the central economic issue. However, he did not champion Georgism as a political movement, because he was convinced that reforms were futile. Elsewhere, he scorned “economism” as a utilitarian obsession with production and profit among the American business classes (similarly, Chodorov saw “Rotarian Socialism,” the political rigging of markets, as a chief stimulant of the growing State bureaucracy).

Nock espoused strict nonintervention, out of concern that the broad powers grabbed by federal agencies during foreign wars would persist in peacetime. His view of classical history reinforced his anti-imperialist reaction to the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II.

Nock had two main disciples: Chodorov, a fervent libertarian, and William F. Buckley, Jr., who adopted Nock’s aristocratic pose but muted his radicalism. Nock’s influence on Chodorov from 1936 onward was immense, and it was Chodorov who administered his estate in 1945. Chodorov passed Nock’s outlook on to the young Murray Rothbard, who would become one of the world’s foremost libertarian economists and historians, and to other late-coming Old Rightists. Nock’s writing strongly influenced the conservative thinkers Russell Kirk and Robert Nisbet as well. Michael Wreszin, biographer of both Nock and the social critic Dwight Macdonald, noted Nock’s deep influence on Macdonald’s criticism of American cultural conformity and complacency.

Nock is also remembered for his much-admired style, of which Chodorov remarked:

Mencken once said to him: ‘Nobody gives a damn what you write; it’s how you write that interests everybody.’ …But it was not exactly true. What Nock said was as interesting as the way he said it.

Wreszin compares Nock to Henry Adams, a self-described “conservative Christian anarchist,” and to Macdonald, as of the 1950s a self-named “conservative anarchist.” Historian George Nash groups Nock with H. L. Mencken and the Southern Agrarians, as “eloquent dissenters,” and Chilton Williamson, Jr., sees Nock as fitting “a peculiarly American dissenting type that, if not properly describable as ‘conservative,’ has nevertheless served as an irritant to the liberal mind.”

Speculating in 1975 on what might replace worn-out American ideologies, the historian of republican theory, J. G. A. Pocock, wrote that “the indications of the present moment point inconclusively toward various kinds of conservative anarchism.” In a similar vein, political scientist George W. Carey wrote in 2003 that Americans should turn from the teachings of the 18th-century Founders and toward those of thinkers like Nock, who grasped “the full dimensions of the modern state’s aggrandizement of power.”

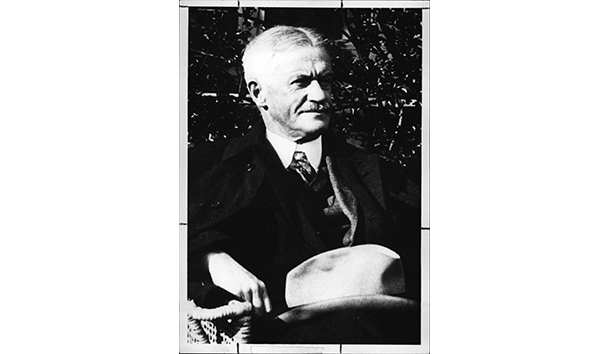

Image Credit: Albert Jay Nock

Leave a Reply